Books

Literature is the mind’s untamed manifestation

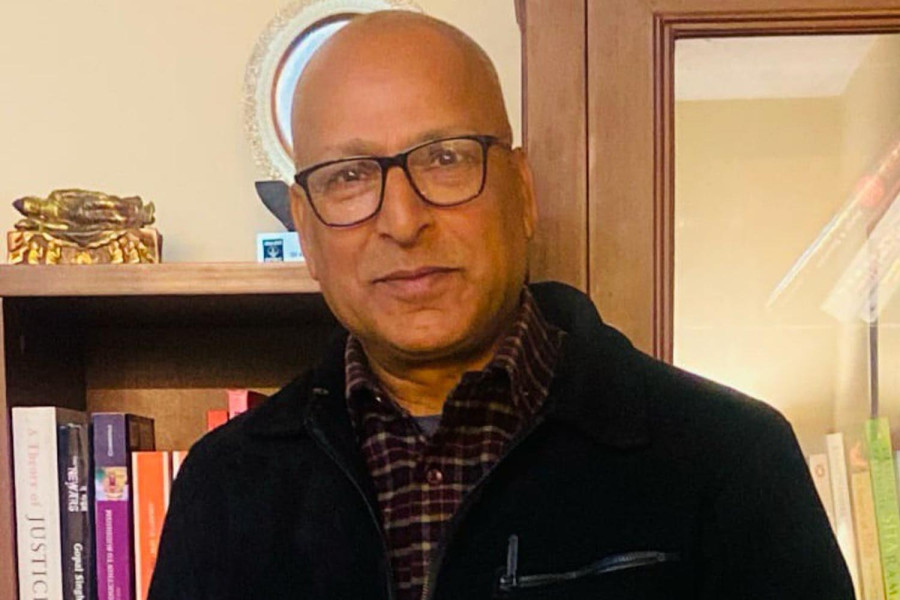

Author Keshav Dahal discusses his upcoming book and his writings on politics, history, and human civilisation.

Sanskriti Pokharel

Author Keshav Dahal is known for his critical writings on politics, governance, democracy, and party dynamics. He has published three books, ‘Nepali Rajniti ko Punarghathan’ (2017), ‘Madhavi O Madhavi’ (2022) and ‘Mokshabhoomi’ (2020), a novel that won the Padmashree Sahitya Puraskar and was shortlisted for the Madan Puraskar in 2021.

Dahal is currently working on a new novel set during the transition from the Kirat to the Lichchhavi period in Nepal.

In this conversation with the Post’s Sanskriti Pokharel, Dahal reveals how books shape his writing and how he balances critique with imaginative storytelling.

What are you currently reading, and has it influenced your writing and thinking?

The books I select often reflect my interests and current projects. A few months ago, I delved into Umakanta Paudyal’s ‘Buddhakalin Samaj’; before that, I read Hermann Hesse’s ‘Siddhartha’. Both works were crucial for understanding Buddha’s era for my novel.

Now that I am done writing my novel, I find myself in a more reflective mindset. During these moments, I often gravitate toward poetry, which I seldom read but resonate with when I do. Last month, I explored Min Bahadur Bista’s poetry collection, ‘Sala Pahadame Kya Hai’, which sparked something within me—excitement and creative restlessness. This inspiration guided me to my next project, prompting me to focus on the present instead of the past.

In reflecting on this change, I became captivated by books that examine human experiences in relation to landscapes, notably VS Naipaul’s ‘An Area of Darkness’ and John Keay’s ‘When Men and Mountains Meet’. Reading them has impacted my perspective and storytelling.

You said you just finished writing your new novel. What is it about?

Yes, I have just completed my latest novel, ‘Itha’. The meaning of its title will be revealed upon release. This story unfolds during the transition between the Kirat and Lichchhavi periods, but it isn’t solely a historical narrative. It weaves together the stories of Vaishali, Magadha, and Kathmandu, focusing on three female protagonists and the rulers they encounter.

The novel examines themes of love, rebellion, and the weight of royalty, ultimately highlighting the sovereign lives of women—those whose names have been forgotten.

What inspired you to write about the transition from the Kirat era to the Lichchhavi era?

I am captivated by the flow of time and the myriad journeys people have embarked upon throughout history. There is something beautiful about tracing our origins, imagining the journeys of our ancestors, and bringing those narratives to life through storytelling.

Recalling and reinterpreting the past fills me with great joy, and this feeling lies at the core of ‘Itha’. To delve into history, one must select a specific moment in time. I was particularly drawn to the transformative era between the conclusion of the Kirat period and the beginning of Lichchhavi rule.

You often write with a historical backdrop. Do you think it is appropriate to blend history with storytelling, as seen in ‘Mokshbhumi’?

I reject the term ‘historical novel’. To me, history must be recorded objectively and without embellishments, while fiction should remain separate. History represents facts, whereas fiction stems from imagination. Writers may place their narratives in historical settings, but this doesn’t classify their work as a historical novel. The mere passage of time doesn’t transform a story into history, nor does a past setting qualify a novel as historical.

I contend that intertwining history with fiction distorts both forms. History should not be idealised, and fiction shouldn't carry the burden of historical accuracy. ‘Mokshbhumi’ is not a historical novel but a narrative about civilisation. There is a crucial distinction between the two.

‘Mokshbhumi’ won the Padmashree Sahitya Puraskar in 2021 and was shortlisted for the Madan Puraskar in the same year. What is its core theme?

My literary journey commenced with ‘Nepali Rajniti ko Punarghathan’, a critical examination of Nepal’s political scene. However, during its writing, I realised that society, civilisation, and human aspirations cannot be fully grasped through a political perspective alone—they must also be experienced emotionally. This insight inspired me to create ‘Mokshbhumi’, a novel set 1,200 years ago.

The book intertwines three key themes. First, it narrates the story of liberation from bondage, metaphorically portraying servitude. Second, it highlights a compelling debate in the Sinja court concerning caste hierarchy versus human dignity, which serves as the ideological cornerstone of the narrative.

Lastly, it chronicles the challenging journey of freed slaves as they forge a new life in Mokshbhumi, symbolising the perpetual quest for dignity and salvation. Through these themes, the novel examines the nature of time, the splendour of life, and the resilience of human dreams.

In ‘Madhavi O Madhavi’, you blend fantasy with nonfiction. Does this risk distorting reality?

‘Madhavi O Madhavi’ embodies creative freedom. Life encompasses more than just facts and truths; it’s also rich with imagination, emotions, and dreams. As a writer, delving into these aspects demands limitless exploration.

While crafting this book, I didn’t restrict myself to reality but let my imagination wander freely. This doesn’t undermine the truth; on the contrary, it facilitates a deeper, more honest understanding of it. By sometimes moving beyond strict facts, we can more authentically capture the essence of an experience.

How do you balance being both a political commentator and a writer?

For me, politics and literature arise from two distinct viewpoints—one rooted in intellect, the other in emotion. I engage in politics by analysing societal issues, civilisation, and human desires through logical reasoning. Conversely, literature comes to life when considering the same topics with feeling and creativity.

Politics remains tethered to reality, while literature offers the freedom of imagination. Finding harmony between the two is difficult. In my political writing, I stay grounded. However, when I write fiction, my thoughts take flight. The mind can be a chaotic and erratic force, and literature serves as its untamed manifestation. Perhaps this is why crafting balanced literature is so onerous.

Keshav Dahal’s five book recommendations

Ashtavakra Gita

Authors: Nath and Baij

Publisher: Kessinger Publishing (new edition)

Year: 1907

This classic is an ocean of knowledge. The dialogues between Sage Ashtavakra and King Janak are highly insightful.

Anna Karenina

Author: Leo Tolstoy

Publisher: The Russian Messenger

Year: 1878

I admire Tolstoy’s intricate stories and vivid language that transport readers directly into the scene.

How the Steel Was Tempered

Author: Nikolai Ostrovsky

Publisher: Young Guard

Year: 1936

This novel highlights the unwavering spirit of its main character, Pavel Korchagin, and his unique ideals.

Madhavi

Author: Madan Mani Dixit

Publisher: Sajha Prakashan

Year: 1983

I am captivated by Madhavi's character. Often, I find myself lost in solitude, thinking about her.

Vaishali Ki Nagarvadhu

Author: Acharya Chatursen

Publisher: Rajpal

Year: 1948

This book uses beautiful language and explains history to enhance our understanding of the present.

15.12°C Kathmandu

15.12°C Kathmandu