Books

Poetry today lacks honesty and finesse

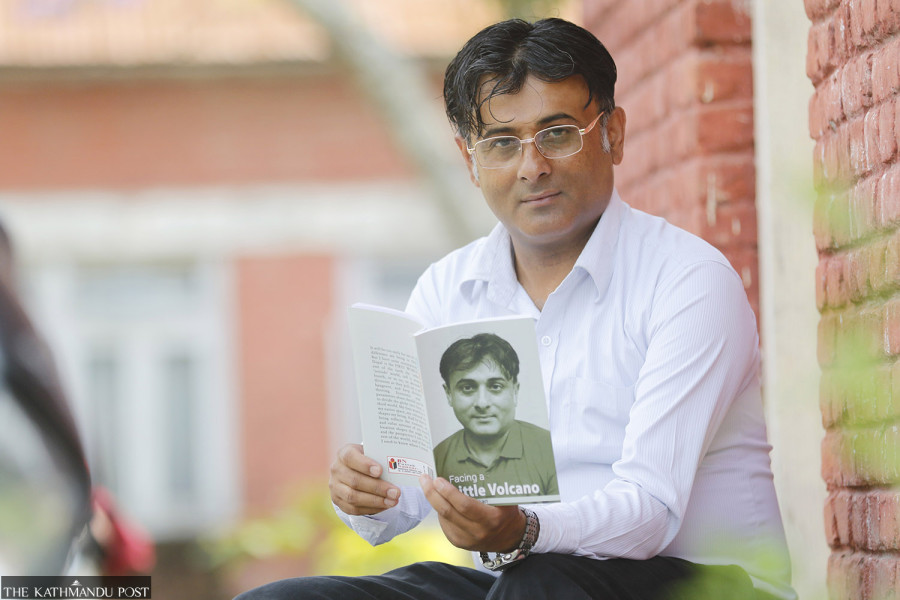

Mahesh Paudyal, a fiction writer, poet, translator and critic, discusses his love for poems and all things literature.

Apecksha Gurung

Mahesh Paudyal is a critic, poet, fiction writer, and translator. He has authored several short story collections like ‘Anamik Yatree’, ‘Tyaspachhi Phulena Godavari’, ‘Aparichit Anuhar’, and ‘Of Walls and Pigeons’. He’s also written a novel ‘Tadi Kinarko Geet’, and the poetry collection Sunya Praharko Sakshi. Currently, Paudyal teaches English literature at Tribhuvan University.

In this interview with the Post’s Apecksha Gurung, Paudyal discusses his love for poetry and all things literature.

What are you reading nowadays?

I’m currently into reading anything and everything about the Nepali mountains. I am trying to unearth what a mountain means to an insider born and raised in the upland. In fact, to a climber coming from outside, a mountain is always a challenge to his or her ego, and conquering it is an act of assertion. However, to an insider, the mountain is a means of sustenance, a source of life, and a natural habitat to live in.

Any specific genre you are into?

Because I write about many things, my preference as a reader too is multi-faceted. Nevertheless, I have a special taste for fiction and poetry because I like the nuances of these genres. I also have a strong attraction towards folk and children’s literature. As a university teacher, reading philosophy and critical theories is my bread and butter.

How did you begin writing poetry?

I entered the universe of writing as a songwriter. I used to write songs and poems during festivals like Deusi-Bhailo. But my first published work was a poem, ‘Oh Chair, My Chair’ in English, published in 1995 in the Shanghai Express, an English daily published in Manipur. My first Nepali poem, ‘Ushako Niyati’ was published in 1997. However, it was in 2019 that my first poetry collection ‘Sunya Praharko Sakshi’ was published. The collection has 108 short poems. It was translated into English and published from New Delhi as ‘The Notes of Silent Times’ in 2020 and in Hindi as ‘Sunya Prahar Ka Sakshi’ in 2022.

Who are some of your favourite poets?

My interest in poetry stems from writing and teaching poetry for so long. There are many poets that I like, but my favourite is Rabindranath Tagore. I also love the works of John Keats, Bertolt Brecht, William Carlos Williams, Langston Hughes and Ko Un. Among Nepali poets, I have always marvelled at the poetic genius of Hari Bhakta Katuwal, Bhupi Sherchan, Bashu Shashi, Dinesh Adhikari, Rajendra Bhandari, Man Prasad Subba, Manu Manjil, Heman Yatree and others.

What are the limitations of Nepali fiction and poetry?

Nepali fiction is heavily dogged by redundant themes, overworked political inflections, predictable plots and a lack of originality. There always is a pandemic of pattern production. For example, recently, we saw a flood of myth or history-based books because one or two of them were awarded. There also is a boom of love-and-sex fiction, political novels, and fiction on migration and diaspora. Only a few have come up with original and genuine works. The same goes for poetry. Poetry today lacks honesty and artistic finesse. Most poems follow fashionable patterns and are products of forced labour rather than genuine creative effort.

On top of poetry and fiction, you’ve also authored many cultural essays and criticism and translated several literary works. What has that taught you?

From my experience, I have realised that I enjoy writing and translating classical works rather than experimentative ones. Some readers call me a traditionalist for this, yet I am happy with my stubbornness because if you look at the Nepali readership, it is not very comfortable with strange experimentations. In fiction, I have always loved to pick characters that are often overlooked. Similarly, my latest critical essays are extremely informal, written in a tea-talk style with a mixture of jokes, fragmented sentences and colloquial expressions. This is a reaction to the fact that the younger generation is moving away from criticism because of the pedantic, impenetrable and complex styles our critics, especially literary theorists, have employed. My experience, after writing 45 episodes of ‘Lekhanka Kura’ made me realise that youngsters will read if you write in a taste they prefer and a language they understand.

What are your thoughts on reading translated literature?

Translated books are our gateways to distant cultural universes. Without such books, we would hardly know who Tolstoy or Chekhov was, why Marquez or Murakami matter, and what makes Lu Xun a great writer. Nevertheless, there are a few promises a translated book should keep. First, the translation should read like the original text, as much as it can. Secondly, translation work, especially in the case of fiction, should be handled by another creative writer who is well-versed in the source and languages and cultures. A bad translation not only irritates a reader but also harms the original writer.

Can you give any advice to someone wanting to write poetry?

If you like poems, be open all the time. You never know when a powerful impression enters your mind and pushes you from within. Take suggestions coolly and patiently. When you think your work is ready, find the best media to publish it. Do not be overwhelmed by appreciation but do not be disheartened by criticism. Remember: tastes differ. Have faith in yourself and strive for the best.

How do you see reading culture among youths in Nepal?

Reading culture, as I see it, is flourishing among youths. Look at recitals, literary festivals, online events, competitions and conferences, and you will see youths dominating the composition of the audience. Online book purchasers, downloaders, bookshop visitors and the quickest reviewers are, most often, young people. They need to be watchful about a few things, however. They are often uncritical and misguided by media hype, advertisements and sponsored praises. Secondly, they are likely to be influenced by certain political or interest groups with an agenda. Finally, they must resist the ‘celebrity syndrome’ and believe in sadhana—genuine and serious hard work.

Mahesh Paudyal’s book recommendations:

A Tale of Two Cities

Author: Charles Dickens

Year: 1859

Publisher: Chapman & Hall

Of Mice and Men

Author: John Steinbeck

Year: 1937

Publisher: Covici Friede

Beloved

Author: Toni Morrison

Year: 1987

Publisher: Alfred A Knopf

Tamas

Author: Bhisham Sahani

Year: 1974

Publisher: Rajkamal Prakashan

Radha

Author: Krishna Dharabasi

Year: 2005

Publisher: Pairavi Book House

Karnali Blues

Author: Buddhisagar

Year: 2010

Publisher: FinePrint

9.56°C Kathmandu

9.56°C Kathmandu