Arts

With over 600 artworks, the 2023 National Exhibition is the most ambitious yet

Nepal Academy of Fine Arts’ annual exhibit brings in artworks from all over the country. This time around, installations steal the show.

Urza Acharya

A wooden figure rests on a chair fashioned out of metal rods used during construction. The faceless figure slumps over the cold metal surface, its body wounded and unpolished. The title of the installation: ‘Khaadi Ma Nepali’ or ‘Nepalis in the Middle East’ by Dipendra Pun Magar. The display feels particularly cathartic because of the exodus of the Nepali workforce to the Middle East and the subsequent exploitation and dehumanisation they face on a daily basis. From the blatant extravagance of the Qatar World Cup to daily news reports of trapped, overworked and underpaid workers awaiting rescue, this particular artwork alludes to a bleak reality the nation and its citizens are currently facing.

‘Khaadi Ma Nepali’ is part of a larger exhibition, namely the ‘National Exhibition of Fine Arts 2023’ organised by the Nepal Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA). Despite its scale and ambition—akin to the Kathmandu Triennale and Photo Kathmandu—the national exhibition (which happens every year) often falters in capturing interest, both within the art community and the general public.

NAFA, established in 2010, is an all-encompassing body formed by the government for the preservation and promotion of the arts. The parliament passed the ‘Nepal Academy of Fine Arts Act’ which mandated the establishment of an organisation that will work for the “preservation, promotion and overall development of fine arts” in the country. An academic council headed by a chancellor runs all the programmes at NAFA. Each council has a tenure of four years, and a seat at the council is a much-coveted position due to its influence within the art and political sphere.

NAFA is responsible for many things—art research, book launches, exhibitions, and talks, but the National Exhibition is an event where its efforts are most visible.

Each year, NAFA puts out an open call in newspapers, social media, and on its website, asking artists from all over Nepal to submit their creations. The mediums can vary; anything from paintings, prints, photography, installations and even performances are accepted. The council then appoints a curatorial team to arrange and make ‘sense’ of the collected works. The team rarely rejects a submitted artwork, mainly to promote art from more rural parts of Nepal, even if they do not meet the ‘standards’ of the valley.

Moreover, NAFA also awards selected artists with a cash prize. The award categories include ‘National Fine Art Award,’ ‘Fine Art Provincial Award,’ and ‘National Fine Arts Special Award.’

According to Member Secretary of NAFA, Devendra Kumar Kafle, this year’s National Exhibition is rooted in dismantling a centralised way of viewing art, wherein the exhibition simply acts as a channel through which viewers can look at the creations of artists from all over the country.

So, what was this year’s National Exhibition like?

Me, my country and my creativity

The 2023 exhibition is divided into two locations—NAFA headquarters in Naxal and the Nepal Art Council (NAC) in Babarmahal. The theme is ‘Me, my country and my creativity.’ NAFA hosts contemporary works, whereas NAC is dedicated to folk and traditional arts.

Pradip Shakya, the curator of this iteration, revealed that this year they wanted to curate the exhibition around the national anthem. “Our initial idea was to honour the individuals behind the anthem, but later, it was decided that we focus on the essence of the song itself,” says Shakya. Certain excerpts and verses of the anthem are plastered across the exhibition spaces.

The exhibition opened on May 28, on the occasion of Republic Day and was inaugurated by Sudan Kirati, the minister for culture, tourism and civil aviation.

With a collection of over 600 artworks, this exhibition is NAFA’s most ambitious one to date. Kafle revealed though a final estimation is yet to be calculated, the exhibition cost is around Rs3.4 million. “Lending to the rent, fabrication, transportation of artworks, cash prizes, staff fees, and other miscellaneous costs, the team is working on a tight budget,” he says. This is also the first time that the exhibition has a thematic structure—though it can be argued that the ambiguity of the all-too-nationalistic (and perhaps not so original) theme feels a tad bit disconnected from the artworks presented.

Exhibition galore

The largest hall in NAFA, with a sizable body of works, emulates a typical white cube gallery. Started as a response to an increased number of abstract works in the 20th century, the white cube’s main purpose was to minimise distraction and let the artwork and light take centre stage. After that, the white cube became a standard for galleries—both in Nepal and internationally—as it not only minimises costs but also works as a blank canvas where curation can take centre stage.

However, as the post-modern era stepped in, the white cube has been critiqued for upholding Western ideals and focusing on the ideas of purity, leading to its abandonment—in the case of both Kathmandu Triennale 2077 and Photo Kathmandu 5.

In NAFA, however, white surrounds the displays. The contemporary works are compact as they chose to fit almost all of the works submitted.

Their efforts are commendable, as the gallery looks neat and well-spaced. Printmaking, photographs, and crafts are given their own sections, ensuring that these budding mediums aren’t lost amidst the heavy collection of paintings. Installations this year were particularly interesting—featuring plenty of social commentary and satire.

The traditional section at NAC is spread across two floors—the first floor dedicated to folk art like Mithila and the second floor for traditional artworks like Paubha and Mandala. The Mithila section is inherently striking, thanks to its vibrant use of colours and attention to detail. However, in recent times, Mithila artworks have opened up to newer forms of experimentation—steering away from the everyday deceptions of Krishna Leela or the Gods—to create works with modern context. Namrata Singh’s ‘Who I Am’ tries to subvert this traditional generalisation as it features women going to school, riding a bike, and using a laptop, all drawn in a classic Mithila style.

The Paubha section—with its mystical and fantastical depictions of several deities, gods and goddesses was notable. The fabrication on the first floor took a grey form, and the bejewelled Gods, with their majestic poses, are seen dancing around the canvases. This particular exhibit is a testament to Nepal’s traditional art sphere, where skills are passed down from generation or taught under the apprentice system.

Some nitpicking

Nepali art is particularly strong in the traditional and some contemporary realms (paintings and prints), but there still is a big gap in digital art and photography. This was quite visible in the exhibition. The submission in both of these categories lacked the depth and nuance that were evident in other mediums.

However, to put the blame solely on the artists would be unfair, as it is true that the art scene (and perhaps, even the audience) places more value on traditional, more established mediums. Because of this, mediums like photography—both analogue and digital—are cast aside, and their inclusion seems more performative than sincere.

There was only a handful of digital art—none that stood out. This medium is also at a crossroads, especially after increased AI-generated content. How the international art community, the galleries in Nepal and even NAFA deal with this transition remains to be seen.

There’s also a lack of finesse—that final bit of touching up—that often adds grandeur to exhibitions. For instance, perfectly arranged labels, consistent fonts on all the curatorial texts, or what the Japanese like to call ‘Kodawari’ (which translates to the pursuit of perfection) are what makes or breaks an exhibition. However, to expect an international standard, ‘Venice Biennale’ perfection from a national exhibition might be too much of a stretch, argues Kafle. “If you look at the exhibition from a very Kathmandu-ite lens, you might see some imperfections,” he says. “But our main goal is to bring exposure to artists from all the nooks and corners of Nepal.”

Curator Shakya also points toward managing such a large body of work, constraints in time and lack of proper resources. “I know one shouldn’t be satisfied, but if you look back at the past national exhibitions, this one is much more streamlined,” he says.

The exhibition will continue till June 13.

—

Khadi ma Nepali

Dipendra Pun Magar

Magar’s sculpture features a wooden figure resting on a chair fashioned out of metal rods used during construction. The figure, with its wounded and unpolished body, hints towards the gruelling labour that migrant workers are subjected to.

Samantabhadra Bodhisattva

Mikmar Yonjan

53X79cm

Mixed media

This particular depiction of the Bodhisattva of goodness and kindness has a certain softness to it; the Bodhisattva’s pale skin is in stark contrast to the dark background. A serene smile rests over his face as he extends a gracious ‘namaste.’

When Time Stood Still

Seema Sharma Shah

Etching

52X105cm

Seema Sharma Shah is an eminent printmaker. This particular work shows the Budhanilkantha Temple stuck in time. The red, yellow and green fabrics hover over the resting stone deity.

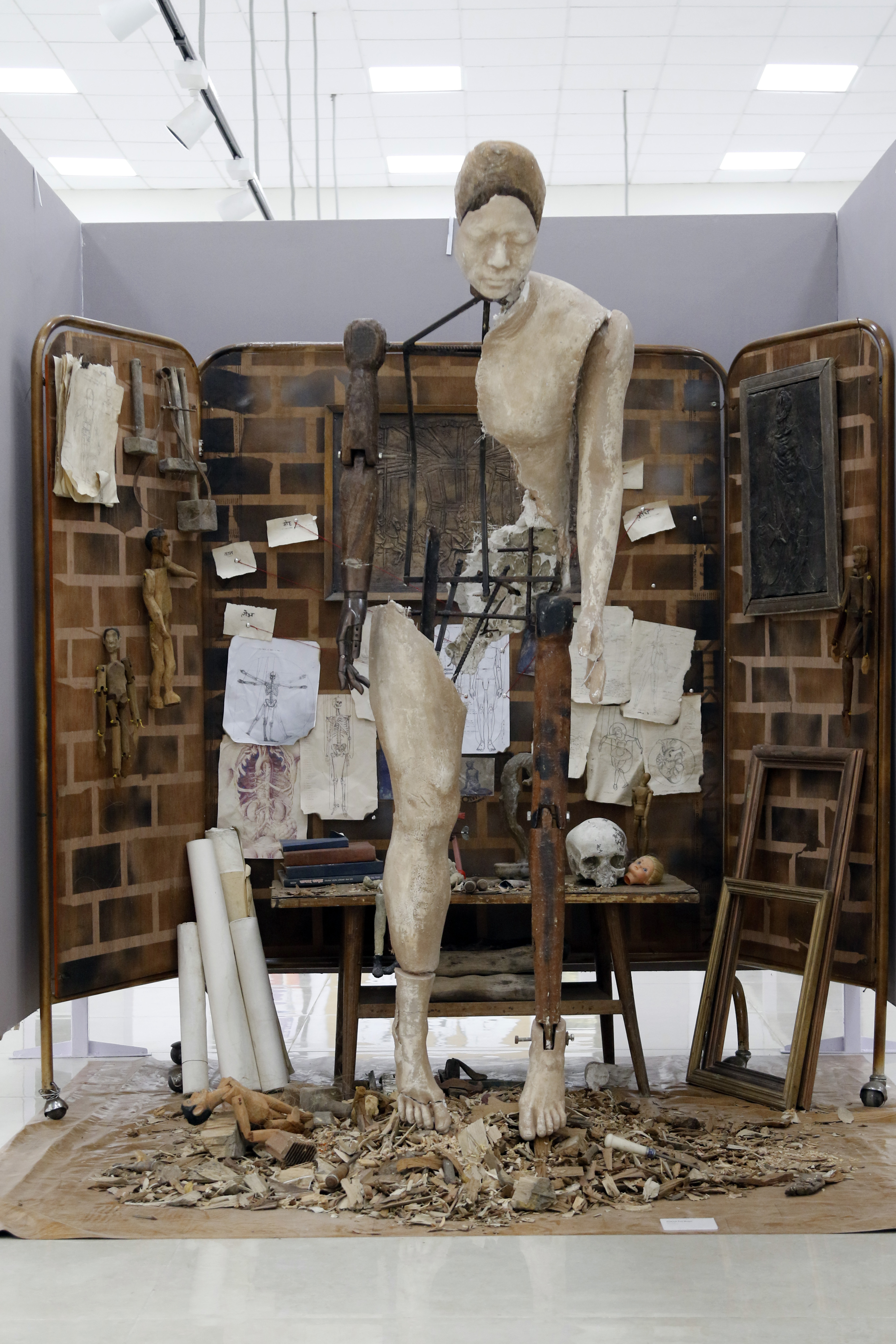

The Metamorphosis

Prakash Pun Magar

This dystopic installation features a figure, perhaps an artist, as hinted by the rolled canvases and paints spread about on the table. The body is seen in transition—either disappearing or manifesting—depicting change.

Ma Ko Ho

Namrata Singh

Acrylic

123X153cm

Drawn in Mithila style, this artwork depicts women performing various tasks—driving a motorcycle, working on their laptop, going to school, among others.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)