Climate & Environment

Forests, parks and ponds can help cool Capital by up to 1.6°C, study finds

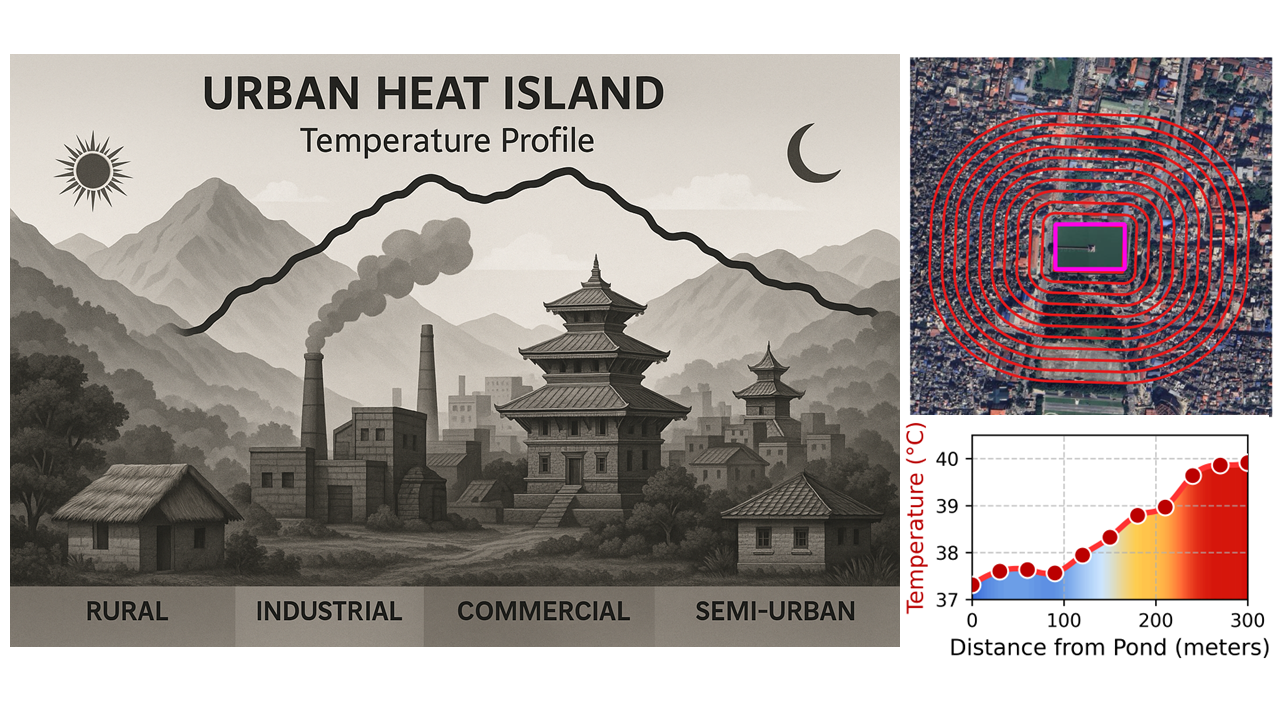

Scientific analysis of 301 parks, 130 forest patches and 26 ponds in Kathmandu Valley offers practical solutions to combat rising urban temperatures.

Sangam Prasain

Urban forests, parks and ponds could reduce temperatures in the Kathmandu valley by as much as 1.6 degrees Celsius if they are strategically managed, according to a new study published in the journal Urban Climate.

This is the first study to examine how different types of blue-green infrastructure contribute to cooling effects across the Valley’s urban areas.

An international team from seven institutions used satellite-based data and machine learning algorithms to analyse 301 parks, 130 forest patches, and 26 ponds within densely populated parts of the Valley.

The study finds that temperatures rise notably as one moves away from blue-green spaces such as forests, parks and ponds. For instance, the Swoyambhu forest recorded a temperature of 31.9 degrees Celsius, compared to 36.0 degrees in adjacent built-up areas—a difference of 4.1 degrees Celsius.

UN Park remained at 34.3 degrees Celsius while nearby areas climbed to 38.2 degrees, showing a 3.9-degree difference. A traditional pond, Na Pukhu in Bhaktapur, registered 39.6 degrees Celsius, while the surrounding urban zone hit 42.5 degrees.

These figures—captured from satellite data over five summers—represent the highest recorded cooling impacts, demonstrating the crucial role these natural features play during peak heat periods.

Although the temperature estimates need to be confirmed with on-ground measurements, relative differences point to clear patterns of urban heat mitigation.

At Ranipokhari, for example, the central water body measured 37.1 degrees Celsius, while the surrounding streets were at 39.8 degrees, hotter by 2.7 degrees.

The study found that the cooling effect of ponds generally extends up to 150 metres from the edge, with the most noticeable impact within the first 100 meters.

In Bhaktapur, Siddha Pokhari recorded a temperature of 36.0 degrees Celsius, compared to 38.5 degrees in nearby urban areas.

Pimbahal pond in Lalitpur showed a cooling effect of 2.1 degrees, with its surroundings at 40.4 degrees, while the pond stayed at 38.3 degrees.

The effect extended up to 300 meters from the water’s edge.

On average, urban forests delivered the strongest cooling, reducing temperatures by up to 1.2 degrees Celsius. Parks followed with a cooling impact of 0.9 degrees, while ponds lowered temperatures by up to 0.85 degrees.

However, the cooling capacity depends heavily on the surrounding landscape. In vegetation-dominated areas, blue-green spaces can reduce heat by as much as 1.6 degrees Celsius. However, in densely built zones, the cooling effect falls between 0.3 and 0.6 degrees.

Lead researcher Saurav Bhattarai, a PhD candidate at the Jackson State University, Mississippi and an ORISE (Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education) fellow, said the findings show that simply adding green spaces is insufficient. “Cooling strategies must be adapted to the local context. Green spaces need to be well integrated into the urban fabric to be effective,” he said.

The study comes amid a steady warming of Kathmandu. Since 1976, average temperatures in the Valley have risen by 0.38 degrees Celsius decade on decade.

Today, core city areas are typically 2–3 degrees hotter than surrounding regions.

Adding to the concern, the researchers found that soil moisture levels across the Valley have declined by an average of 2.1 percent in the past 10 years. In some central areas, the reduction has been as high as 35 percent.

Dr Rocky Talchabhadel of Jackson State University stressed the urgency of urban climate planning. “Our study shows that Kathmandu’s densely built areas are especially vulnerable to extreme heat. Without immediate intervention, these heat islands will grow,” he said.

Urban forests showed the strongest correlation between size and cooling impact: when forest area doubles, the cooling effect increases by roughly 30 percent.

Parks, on the other hand, showed that cooling effectiveness depends more on internal design than size. Tree canopy coverage was the single most important factor.

In small parks, a 1 percent increase in high canopy coverage led to almost a 1-degree increase in cooling. In large parks, the same increase brought a 1.76-degree drop in temperature.

“This isn’t just about planting more trees,” said Professor Vishnu Prasad Pandey at the Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering. “The ratio of tree canopy, grass and paved areas within a park influences cooling more than size alone. Well-designed parks can be powerful tools against heat, even in space-constrained cities.”

The study offers tailored recommendations for different urban contexts.

In dense urban cores, the priority should be preserving existing mature trees and introducing water features and rooftop-based solutions like cisterns, reflective pools, green roofs and rooftop farming.

In transitional areas—those between urban cores and vegetation-dominated zones—the focus should be on expanding forest patches and designing parks with large, continuous tree canopies for maximum shade.

In greener zones, protecting existing forests and establishing buffer areas can help prevent the future emergence of heat islands.

Dr Prajal Pradhan of the University of Groningen, Netherlands, said the methodology and results have global implications. “Cities around the world can learn from our Kathmandu-based study. We offer a practical framework that can be replicated to evaluate and improve urban climate resilience anywhere,” he said.

Dr Nawa Raj Pradhan from the US Army Engineer Research and Development Centre warned that the health impacts of unchecked urban warming could be severe. “If no action is taken, rising temperatures will strain public health systems, drive up electricity demand for cooling, and disproportionately impact the most vulnerable communities,” he said.

The study estimates that integrated cooling strategies could reduce energy demand for cooling by 15–25 percent in urban areas, potentially saving significant electricity costs while improving public health outcomes.

The researchers encouraged residents to get involved in heat tracking and climate adaptation. Comparing temperatures in city parks and nearby roads during mornings and evenings using simple thermometers can help people understand local heat patterns.

The team recommends avoiding outdoor activities between 12:00 and 15:00, choosing shaded or tree-lined routes, and recognising symptoms of heat stress such as excessive sweating, dizziness and fatigue.

Practical personal strategies include wearing light-coloured, breathable clothing, carrying water, and using hats or umbrellas for shade.

Residents are also urged to join municipal tree-planting campaigns focusing on native species such as peepal, banyan, and nim, participate in pond-cleaning drives, and report illegal pond filling to authorities.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu