Arts

In the current pandemic, there is much at stake for the Nepali art scene

The uncertainty of these times will have a lasting impact on the art ecosystem of the country—one that it might take years to recover from.

Srizu Bajracharya

Just a few days before the first Covid death in the country, a virtual exhibition titled ‘Tangential Stress’, organised by the Museum of Nepali Art, went live on May 14. In the exhibition, one artwork was of a pregnant woman, protecting her womb with her hands.

“It was almost like the artist, Ranju Yadav, was making a prediction,” said Sangeeta Thapa, director of Siddhartha Art Gallery, commenting on the poignant artwork, which drew attention to how the current pandemic could prove to be threatening to pregnant women.

Amid the nation-wide lockdown, the art world too has now fallen silent—with art exhibitions, discussions and openings all called off, all galleries closed, and events postponed indefinitely. The virtual exhibition ‘Tangential Stress’ is one of the few initiatives that’s keeping the country’s art community breathing.

“In every crisis, the art community has always suffered gravely,” said Thapa.

The Nepali art sector had only just begun to gain some momentum, after a slow recovery from the 2015 earthquakes that had devastated the country and the art community too. “And now, with the pandemic, we will be going 10 steps back and perhaps, it will take us at least two years or more to revive,” she said.

As the Covid-19 spreads across the globe aggressively, social distancing has become key to combating it, but gatherings and networkings are what keeps the art community thriving. And even after the lockdown is lifted, it is unlikely that things will return to be the same for the art community. “With no sales and exhibitions, many art galleries will probably be at risk of closing down,” said Thapa. “And it is understandable as art isn’t a necessity right now, even though it’s for me.”

The Museum of Nepali Art (MoNA), slated to be the only contemporary art museum in the country, is Rajan Sakya’s ambitious project. Given that the country has never had such a space, Sakya, an avid art collector, believes such initiatives will bring in art investment into the country and give more power to Nepali artists. “Around the world, Nepal is mostly recognised for its traditional art and crafts. But our potential is so much more,” says Sakya, who is the CEO of KGH Group.

With the lockdown, his plans for the museum and future investments have now been put on hold. But continuing forward with his project to establish Nepali artists as household names, Sakya soon after the lockdown started reaching out to 19 artists through artist Asha Dangol. The idea was to make a statement about the challenging time people are going through. Ranju Yadav’s ‘Pregnancy during Pandemic’ was also a part of the same exhibition.

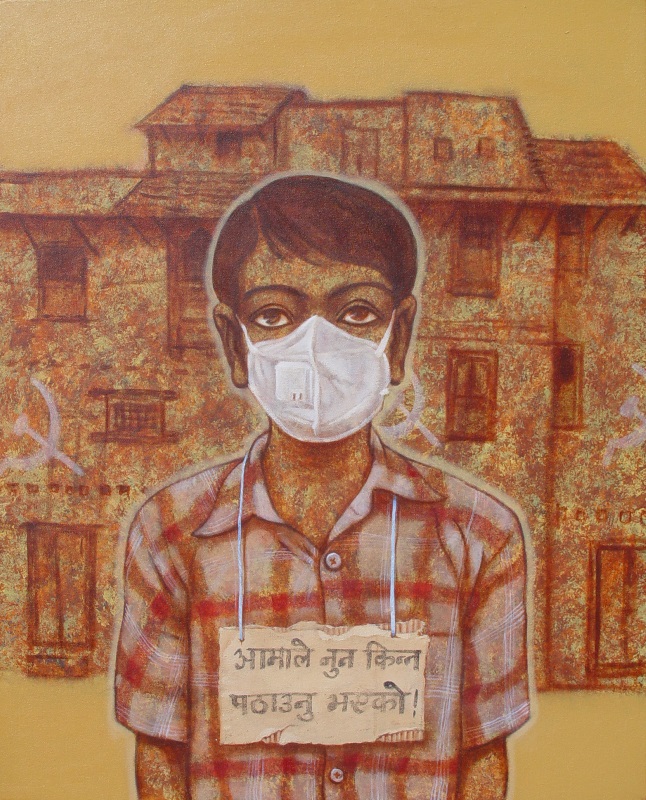

In another one of the paintings at MoNA’s virtual exhibition, by Bhairaj Maharjan, we see a boy wearing a mask outside his house, with a placard that reads, “Aama le noon kinna pathaunu bhayeko” (My mother sent me to buy salt).

“Art is significant in voicing the realities of society, and I wanted to portray through art the struggles people are facing during this pandemic,” said Maharjan. “But art isn’t a basic need, like salt, which means the trade of art is going to be difficult after the lockdown. For artists, sustaining could become an issue,” he said.

And with the global economy plunged into a crisis, the art sector has been pushed to an edge. The commercial art sector for a while will have no investment, and galleries—old and new—will be at risk, says Sharareh Bajracharya, an arts educator and director of Srijanalaya. And with unexplored online avenues, the foreseeable future of the art sector looks more uncertain than ever.

“The virtual exhibition that MoNA is doing is commendable,” says Bajracharya. “But for the art community, this is going to be a challenging time, as we haven’t established an online presence in the first place,” she says. Internet access is still problematic in most parts of the country and digital archiving is still only a concept. Furthermore, effectively grabbing audiences’ attention virtually is another challenge altogether.

There is also the question of limiting art’s reach if exhibitions were to go online. Over the years, there have also been discussions about the disparity between the Nepali contemporary art and the public. But now as the artists move their work to the online platforms, artists and curators are worried that artworks perhaps may not find their audience, or be able to give an experience that people get from visiting an exhibition.

“But at a time like this, we have to accept the only option we have. I have also realised in the past few days, manoeuvring art in the digital space is not something impossible. The virtual world has a lot of possibilities, and it is more diverse and opens the art world more,” she says. Many art galleries and institutions around the world have also turned to hosting virtual exhibitions and discussions.

Beyond art in galleries, even for art students, who will take forward the art community, problems persist. Virtual classrooms are proving to be problematic. “Online learning isn’t easy for art students, as we also depend on tactile experiences and practical courses. And virtual learning is limiting as we are demonstrating and giving discourse through the screen,” says Sujan Chitrakar, associate professor at KU Art+Design.

But despite the shortcomings of virtual learning, KU is planning to finish its course by July. “The current time will definitely make an impact on the lives of these students too because the art sector can only thrive when the economy of a country is strong,” he says.

While the business side to art has been put on hold amid the lockdown, art has become much more personal for many. Around the world and in the country, people are turning to painting and other artistic endeavours as therapeutic and recreational tools. And this role the arts plays in people’s lives is something that the art community can work with in the coming future, says Chitrakar.

“Maybe we will have to see how we can help people in these times through art. We can work around art as therapy or see how art can be a part of learning in schools. We can holistically approach this problem and reinvent our ways of making and communicating to people through art,” he says.

Keeping in mind the uncertainty of current times, the future of the art community is grim. But artists have to be patient and rely on the passion of art to keep continuing on their journey, says Chitrakar.

“Despite everything, artists must do what they do, they need to keep making art,” says Chitrakar. “Besides, it’s just the commercial value of art that has fallen down; art as life still continues and artists must learn to give back to society with grit, while the society recovers from the damage of the pandemic.”

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)