Entertainment

‘Folk music is the soul of Nepal’s agrarian history’

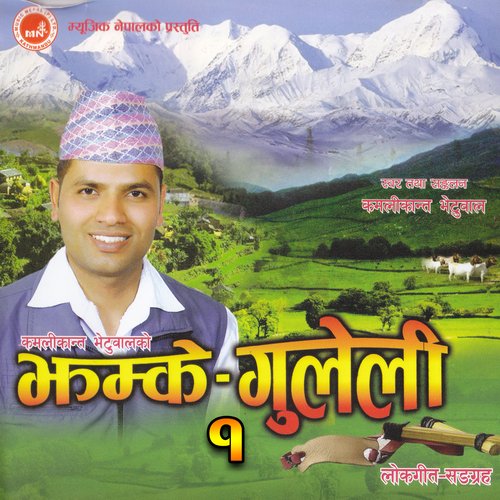

Kamali Kanta Bhetuwal’s song ‘Jhamke Guleli’ struck a chord with many because of its purbeli tone, accompanied by earnest and imaginative lyrics.

Urza Acharya

Kamali Kanta Bhetuwal grew up in the hills of Sankhuwasabha. His was an agrarian family—deeply entrenched in the labour of soil. When he was only nine or ten, Bhetuwal accompanied his grandfather to the fields. As his grandfather walked the soil with halo (plough), he sang. Some of his tunes were hopeful, others were melancholic—but all reminisced about the perils of the agrarian life. “I could’ve spent hours hearing him sing,” he says.

Even as an adult, he still hasn’t been able to give those songs up. But now, he isn’t just a listener. He also sings, collects and composes tunes in the Purbeli bhaka (tunes from eastern Nepal), hoping to preserve them for future generations. One particular song, ‘Jhamke Guleli’ found notability after Bhetuwal first recorded with Radio Nepal in 2009. Purbeli bhakas are known for their mellow, soft music and sombre lyrics, featuring allusion to nature, religion and romantic love. Songs like ‘Jhamke Guleli’ and the iconic ‘Wari Jamuna’ by Khem Raj Gurung have become synonymous with Eastern folk music practices and have garnered a lot of devoted audiences.

Bhetuwal was drawn to lok geet (folk songs) because he finds them calming and honest. “Village elders used to sit under the Peepal tree and hum tunes about their hardships. But somehow, the tunes were always hopeful,” he remembers.

Bhetuwal was introduced to aadhunik geet (modern songs from the 1970s) when he came to Dhankhuta after his SLC (now SEE) exam. “Back then, Radio Nepal was the single most influential medium,” he says, remembering how he became enamoured with the songs played there—tunes by Narayan Gopal, Kabita Ale and the like. Even then, perhaps because of his upbringing, he was still drawn to folk tunes rather than the then-experimental music of musicians from the Valley.

By the time he entered Kathmandu, Bhetuwal had already collected several local tunes and verses from his hometown. “I realised I needed to document these tunes before they became obsolete,” he says. So, surviving on the money his father sent him, he began frequenting the premises of Radio Nepal, hoping to have one of his songs recorded. Of many songs he pitched to Radio Nepal, his mentors liked the novelty of ‘Jhamke Guleli’, which became his first recording.

The chorus and tune for ‘Jhamke Guleli’ isn’t his, Bhetuwal admits. With folk songs, it is often difficult to point out one person as the sole creator, as the tunes are usually picked up by multiple people and modified according to their experiences. “I first heard it through my maternal uncle, Guru Prasad Subedi, an incredibly talented man with a voice smooth as honey,” he says. “When I asked him if I could borrow the tune from him, he gave me his blessings.”

As the recording began, the song caused a bit of controversy. A part of its now iconic line, “Ma auda chai oi bhana hai, jhamke guleli,” (When I arrive, call me over by yelling ‘oi’) was deemed inappropriate by those in Radio Nepal. Originally, the ‘oi’—an exclamatory phrase used to attract someone’s attention—was actually ‘poi’, an informal slang for a husband or male lover.

“I was told ‘poi’ rendered the song vulgar. But that was part of the song's original lyrics, and I didn’t want to change it,” he says. In a way, the lyrics was sanitised for the Kathmanduite ears—and according to him, he was asked to abandon the essence of what made the song so entrenched in folk culture. “Eventually, I decided that ‘oi’ would be the best replacement,” he says.

After its release, ‘Jhamke Guleli’ became a hit. Bhetuwal’s eastern dialect, accompanied by imaginative lyrics, struck a chord with many Nepalis—especially those reminiscing about their village life from the city. The comments under its YouTube release—which has over 1.3 million views—are evidence that the mellow tone of the song brought back memories of childhood and a simple time. After the song’s success, he recorded ‘Maga ma Maga’, ‘Jhim Jhim Pareli’, and ‘Pathhar Koila’, among others.

For his recording of ‘Jhamke Guleli,’ Bhetuwal reveals he was given Rs400 as an artist fee. “I wasn’t worried about money at the time; I just wanted the song to reach the masses,” he says. Fearing that the song’s original recording might get lost, he eventually digitised and sold it to Music Nepal for a meagre fee. “I was told I would get 60% royalty whenever my song was used. I received around Rs15,000 during the early years, but they haven’t called me for the past few years,” he says.

Music Nepal, one of the largest music distributors in Nepal, has been accused by artists of depriving them of royalties—especially those earned through digital platforms. For instance, in 2014, Music Nepal uploaded a playlist of Bhetuwal’s music titled ‘Jhamke Guleli Jukebox’ with over 900,000 views. However, he now has little to no distributing rights to own songs and doesn’t receive compensation for any songs uploaded online or played at events.

“Every time I ask them about TikTok and social media, they act clueless,” he says. “As long as they continue providing these unique folks tunes to the masses, I’m willing to live with the compromise.”

Bhetuwal reveals that he was also approached by Music Nepal to re-record ‘Jhamke Guleli’ and modify the song to fit the modern context to make it more palatable for the budding audience. However, he refused. “They wanted me to add quirky one-liners and lyrics with innuendos, which I declined,” he says.

Bhetuwal feels that folk songs are currently facing a crisis—one of vulgarity and sensationalisation. Perhaps to compete with the saturated market, modern folk singers have abandoned the soft and melancholic tunes of the past and adapted a more commercial approach—borrowing local tunes to sing about sex and physical attraction. This phenomenon, termed by one writer as ‘cringe/vulgar folk’ or ‘chaada lok’, garners millions of views despite scrutiny. Moreover, it is also marred with misogyny, colourism and overt sexualisation of its female dancers and actors.

“Folk songs are getting a bad rep because of how misused they are. It has come to a point where it’s embarrassing to associate with lok geet,” he says. “That is truly heartbreaking.”

Despite hardships, Bhetwal’s love for raithane bhaka hasn’t diminished. He has travelled to almost all districts in the East—from Sindupalchowk to Tanahun and Bhojpur and has collaborated with and collected local tunes from villagers.

“I have hundreds of recordings and verses saved in my phone. Right now, I don’t have the resources to record them all. But eventually, they will be brought to the audience,” he says.

Along with singing and composing, Bhetuwal is currently doing a PhD in folk songs—studying the phenomenon of ‘code mixing’ in folk music. In the context of his research, code mixing refers to the use of non-Nepali words—say Sanskrit or Hindi—in Nepali language folk songs. “I’m trying to figure out ways through which new words are added to the folk lyrics,” he says.

Bhetuwal reveals that he is eternally thankful to his grandfather and village elders who instilled in him a love and pride for folk music. “These songs were a way to come together and share our feelings at a time where talking openly about things wasn’t common,” he says. “Folk music is the very soul of Nepal’s villages—especially how it celebrates agrarian lifestyle.”

13.25°C Kathmandu

13.25°C Kathmandu