Entertainment

It’s time to rethink the arts

In my uninhibited foray into art, I have descended down the chaotic labyrinth of my untamed madness and, like Gibran, felt an urge to throw off my masks, put to test my inadequacies and fears, to breathe, to survive, to be. My madness has become my freedom.

Ayushma Regmi

And so it goes.

Four words have already been written. Each word carefully chosen, weighed, chiselled and polished to produce the right effect. An effect in the way of thousands of effects that have already been sanctioned, executed, succeeded. This is the legacy of the written canon. I drape it around myself and plod along, carrying nuggets of the past knowing, into the knowable future, producing predictable outcomes. I send my writing to my editor, who—not being a man of many words—gives me the most understated of applause. Good piece, thank you.

Immediately, I swell in the safety of what I have done. I wait for the work to get published. Anticipation rising. Knowing that each compliment I receive will keep me rising in my own ranks.

And then, in a random conversation with a friend, this line by Gibran comes up, and frankly knocks my socks off, leaving my knees hobbling and my mind in a jelly-wiggle: “And I have found both freedom of loneliness and the safety from being understood, for those who understand us enslave something in us.”

And then, in another time, in another room, I remember. My being had felt that shattering freedom of loneliness. And in not being understood, I had let my inner child roar to pieces of paper. How I had smudged delight on them, pierced them with my pain. Sometimes, there were no more than scratches that, together, spoke one word: rage! What did it matter that I was depraved, or tender, or petty, or generous, or naïve, or wise, or cruel, or fraudulent? What did it matter that there was nobody to read any of it, let alone understand? Those who understand us enslave something in us. And so, as a teenager, perhaps I was saved, at least temporarily, as I galloped through galaxies, printing word after word after word on stars whose light had no scope of ever reaching my world.

As I brought my writing closer to the order of this world, to the consciousness of my people, I let their reactions arrest me. Even the most earnestly shared response, an uninhibited smile, a look of wonder, a hand pressing mine effusing feelings of gratitude, a verbal accolade, an emoji heart, all got me beaming and healthy. But every compliment brings with it a shadow reaction, lurking, unsaid, but volatile, and just as powerful. This dreaded criticism could potentially badger a fragile ego, and in order to avoid it, I too, set about shaping and reshaping my words, mutilating my process and hanging my writing for others to see, now pretty, but also grotesque, as if birthed by an alien and not me. That desperate desire to fit in, to belong, to be acknowledged and validated, haven’t we all felt it? Art can easily become a sinister means of pursuing that.

But then, there’s also this thing I now do with my body. Which I realise I have done for as long as I can remember. Which is basically to move about, arms flailing, limbs jerking, torso twitching to the movement of whatever auditory rhythm is available. And then, I have to chuckle at the memory of just how bad I was as a student of dance, how resistant I was to the order of regulated, premeditated movements. How my body just wanted to do its own damn thing and how learning it from some expert only served to cause a separation between me and what I was doing. I became a terrible student. I should say I failed. It is only now that I am struck by the importance, nay, the indispensability, of failure in just letting us live with the arts. Because there is nothing more corruptible than success.

So now, I inhabit my body, let it move, and groove, and sway, and glide, cherishing these imperfect movements, revelling in my smallness as an ‘artist’. I sing, too, mostly alone. And it is while I am belting out squeaky tunes, or drawing sketches on the edge of non-sketch books that will forever remain unfinished that I find that art is my toy, and I can use my body, my mind, this material world around me to play with. It is what lets me access the deepest, darkest, loneliest, but also the lightest, brightest, loveliest parts of myself. It is art that I use to live, to breathe, to survive. In the midst of such rampant institutionalisation and standardisation of our souls, how else? Art, my private act of care. My own.

And then, I see kids today. With parents who send them off to dance classes or art classes, or numerous other self-improvement classes from as little as age three. How easily interest leads to submitting kids to a history of codified knowledge, with the unconscious intention of making them experts, eventually. So they fall into it like a grind that is to churn a perfect product out of them. And they begin to think of themselves as either good or bad, both feeling the need to get better. Trapped in a continuum of time where the future prematurely presses its ugly, orderly, practical, profitable, reasonable, constructive agenda on their frail and nebulous beings.

Is there no space for spontaneity or play in our lives anymore? Adults will scoff at the thought of playing. But what about children? Couldn’t the arts be something for them to explore in the here and now, without precedence and promise of future fortunes? Every human being engaging with art can be the first one to do so; that is its beauty and it’s magic. Collectively, I see how afraid we have become to claim something for ourselves entirely. How small and inadequate we’ve been made to feel that it seems inappropriate to seize and celebrate ourselves through such unfettered engagement, through unrestrained play.

And then, of course, I think of toys, those products of corporate machinery that pile on another layer of standardised bullshit on our young ones. Patented toys come with the implicit assumption that children need guidance, assistance, externally enforced rules and ready-made materiality in order to play. It is brutally disempowering to the inherent capacity for play that children are born with. It is callously depriving kids of nature, of freedom, of spontaneity, and of the grit and gift of their own devastating loneliness.

In my uninhibited foray into art, I have descended down the chaotic labyrinth of my untamed madness and, like Gibran, felt an urge to throw off my masks, put to test my inadequacies and fears, to breathe, to survive, to be. My madness has become my freedom.

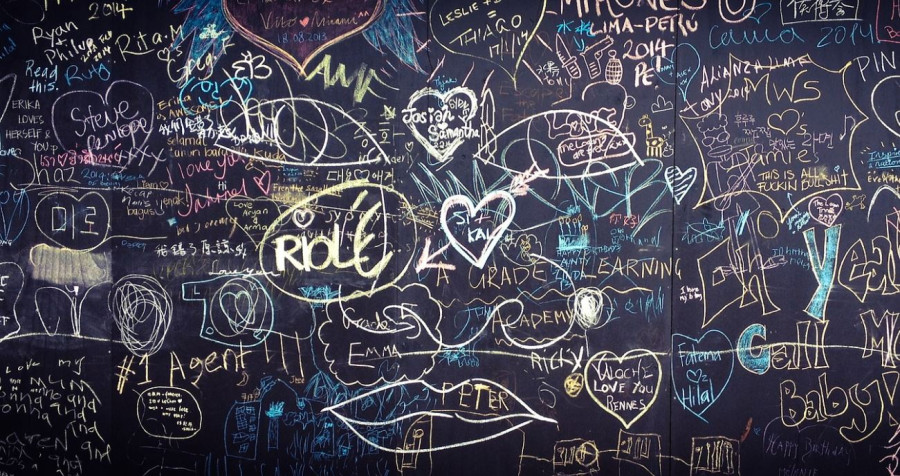

As festivals of art, literature and music loom about us, where ‘artists’, ‘writers’ and ‘musicians’ sit stiff and unsmiling, canonising art with their rigid presence, and where curators dole out their preferences and prejudices in the name of expertise, we run the risk of forsaking some of the most primitive pleasures and wholesome health that art can afford us. Isn’t there something in the politics of the individual to reclaim the arts, to find it okay to exercise absolute agency in the act of creation? To meddle, to destroy, to play, to go insane?

14.24°C Kathmandu

14.24°C Kathmandu