Entertainment

Feminism through art

Studying Art History at what can only be described as a hyper-liberal arts institution in the US exposed a young brain to two people who changed the way I perceived the world.

Sophia L Pandé

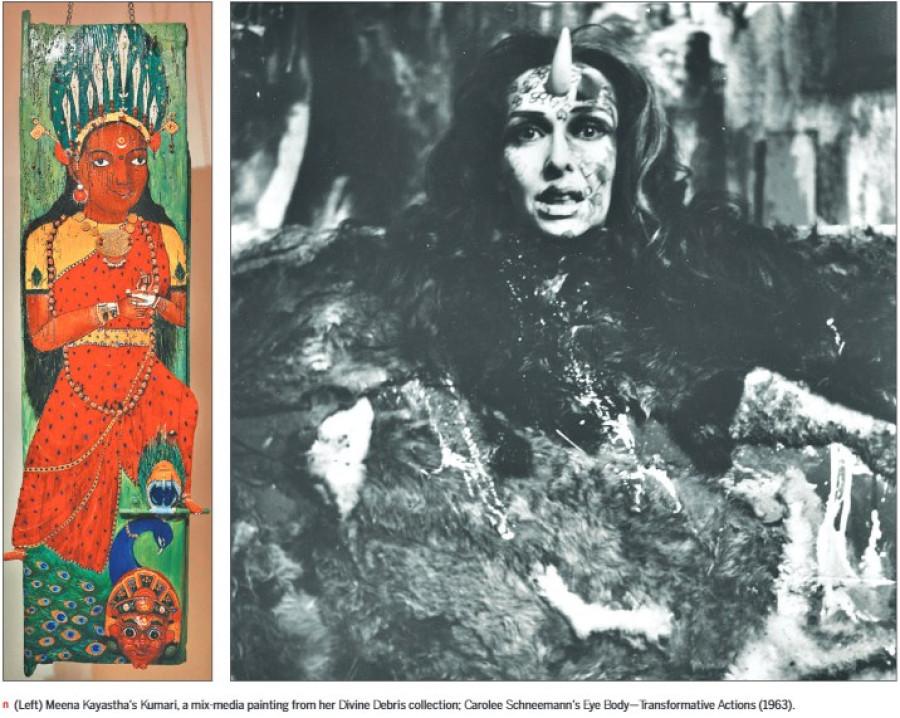

Studying Art History at what can only be described as a hyper-liberal arts institution in the US exposed a young brain to two people who changed the way I perceived the world: Ann Steuernagel, a video artist and my professor in our eccentric, experimental film-making classes, who in turn introduced her awe-struck group of students to the avant-garde artist Carolee Schneeman, in person, an already towering figure then in artistic circles, but only now beginning to come into her own with a retrospective at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg in Austria in 2016, and a two-part show at Gallery Lelong and P.P.O.W. in New York.

In the 1960s, when Schneeman started off, the very famous people in art, ie the artists and the critics, were men. Schneeman trained as a painter but very soon her very particular instincts towards upsetting the status quo won and she embarked on her now remarkable career in which she has broken every boundary imaginable, making the most profoundly irreverent, shocking, moving, mixed media work, in particular video art, that paved the way for many artists today from the likes of Tracy Emin to Ragnar Kjartansson who owe her the debt of having taken on the flak from art critics who viewed her work as pornographic (because she is almost always in her own work, nude), and first wave feminists who perceived her as provocative (not in a good way) and a narcissist.

It is Schneeman who strove to cast aside the forced boundary between women and what is considered “high” art. Women were depicted in fine art by painters who were men; women could not, however, make fine art according to men. Schneeman sought to be both image and image-maker, controlling herself how her body was depicted by making her own work and inserting her person within them.

More than 50 years later, in a “modern” world that considers itself post-feminist, there is still an urgent need for gender politics in art, particularly in Nepal where so many women’s voices are still unheeded.

On the heels of two women dying in menstrual huts in remote Western Nepal due to the chhaupadi practice, where women are barred as being unclean and bringing ill-luck during their cycles, in an ongoing practice deemed illegal by the Supreme Court in Nepal, there is still an impassive, most of the time utter, rejection of the issues that affect women, from the denial to give citizenship to their children to rape, sexual harassment, emotional abuse, and just plain gaping imparity perpetuated by both men and women who turn away from acknowledging and addressing these issues head-on.

It is in this world that Meena Kayastha, a Bhaktapur native, artist, wife and mother, who saw her hometown in shambles after the earthquake, made her mixed media pieces for the show Divine Debris, which will end shortly at the Siddhartha Art Gallery.

Working from a very particular point of view, Kayastha draws on her personal experience as a woman growing up in Nepal watching other female figures around her struggle with the limits imposed upon them. Human experience does not always allow for much empathy, and so the lived experiences of women who struggle with puberty, menstruation, childbirth, child-rearing, taking care of multiple family members including their husbands and in-laws is rarely seen as anything extraordinary; this kind of role juggling is taken for granted by the world without much compassion for the physical and emotional toll.

The show consists of deities depicted on narrow, old wooden doors salvaged from the ruins of traditional, Newar Bhaktapur homes. These mixed media works, adorned with found objects and other unexpected embellishments, are symbolic of the women in Kayastha’s lives who have transcended the ordinary in their quotidian, domestic struggles, moving into the arena of the divine, the doors signifying the paths and openings that some of them were never able to take.

Ultra feminist art often makes people uncomfortable, making itself exclusive. Life is enriched by access to one’s emotional intelligence, and empathic concern; stepping outside that which makes you comfortable will afford one with the opportunity to understand something new.

The Schneemans of this world went through trial by fire to allow people like me to write a column like this, where I can protest about inequality, somewhat able to control my own narrative, just as Meena Kayashtha can now control her image to tell her story. Both would have been impossible in Nepal 20 years ago.

With artists like Kayastha working in contemporary art today, Nepal is moving towards its own sort of catharsis. There may come a day when women are liberated from the shackles of superstitious insularity, and callous unconcern, but the road is long and hard, and many brave voices will have to speak their minds before we move into a world of real equality.

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu