Entertainment

Interpreting unfamiliar cultures

David Best, of Burning Man fame, strung together available scraps to create a piece foreign to his culture, as did the Nepali edition of Hamlet currently being staged at Theatre Village

Kurchi Dasgupta

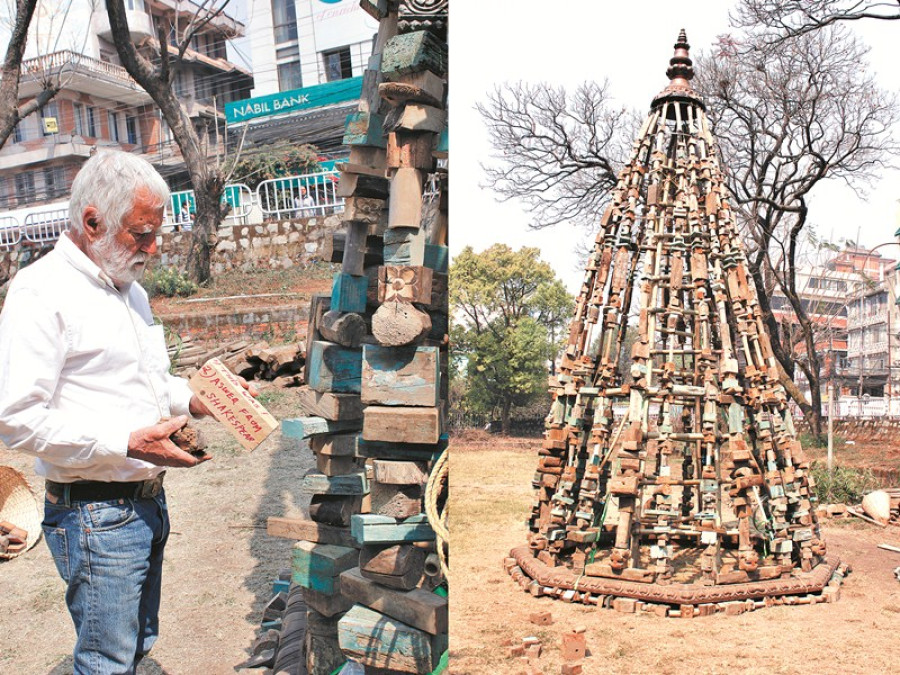

Walking past the back wall of the Nepal Academy in Kamaladi, an intriguing pyramidal structure draws your eyes. I was lucky to have witnessed its construction a month ago, during the World Wood Day festival. David Best, of Burning Man fame, and his team of volunteers was putting it together when I walked in to take a peek at the amazing array of wood carvings being exhibited there from around the world.

Best had apparently been approached by residents of the Bungamati village to rebuild either the Rato Machindranath or Bhairav temple that they had lost to the devastating earthquakes last year. Responding to the call, Best and his team flew in, partially funded by the International Wood Culture Society. The situation on the ground was not exactly what they had expected and the project soon morphed into the exciting, creative process of building a large scale art installation instead of the originally intended rebuilding of a collapsed temple. Best’s team, including the young architect Steven Brummond, settled in with the residents of Bungamati before setting about taking stock of their actual needs. They spent a lot of time with the community, listening to their experience of the devastation before deciding that it would be ethically wrong to direct resources towards rebuilding a temple when people were lacking homes and essential structures like schools. The neatly planned blueprint of a seismically designed temple was scrapped and Best and Drummond instead decided upon creating an art piece from wood scraps to commemorate the thousands of lives lost.

The group of volunteers began scavenging for pieces and beams of wood from the earthquake debris, before painstakingly cutting these up and drilling holes through to create wood blocks that could be strung together with rebars. Their new aim was to make the process as low impact as possible on the country’s already scarce resources and be able to build a structure reminiscent of the fragile beauty and massive scale of a Best temple at Burning Man. The main structure we have at Nepal Academy is 20 feet tall with a base diameter of 10 feet, with a smaller alter accompanying it. The approximate number of the recycled wood pieces coincided with that of the number of victims, but unlike Burning Man, the Nepal Temple project will not go up in flames but will instead remain in situ as a symbolic vehicle for healing. A few blocks had messages written on them by random visitors, and Best picked one up as I poised my camera and it uncannily read, ‘Answer from Shakespeare!’.

The fact that Best’s team responded to the situation on the ground with humility and empathy as they tried to interpret an unfamiliar culture without compromising their own eco-conservationist values is a point of departure for me. For I now connect their project to yet another effort at adaptation, this time by an acclaimed and local theatre group comprising Nepali actors. Theatre Village is currently staging a Nepali adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and like Best, they do so with empathy for the original text ensuing from a culture that is distant both in time and space. Part of a global project initiated by Globe Theatre to commemorate the playwright’s 400th death anniversary, the Nepali Hamlet is directed jointly by Bimal Subedi and UK’s Gregory Thompson and will happily be presented in London in May, right after the show closes in Kathmandu—a rare honour indeed!

As Best had strung together available scraps to create a new piece, so has the Nepali edition of Hamlet. The play being staged does away with nearly a third of the original Shakespearean text, though aptly translated by Shristi Bhattarai, and sometimes brings to question the justification of tampering with the structure classic texts. Shakespeare, like classic Bollywood films, had a knack for coming up with a perfect balance of emotive scenes with strong narrative continuity and symbolic nuances and taking away from these inevitably puts a production at risk. I particularly missed the ghost walking scene at the ramparts at the very beginning for its ‘in medias res’ impact, the exclusion of Laertes aka Lalitjung adeptly played by Sandeep Pokhrel from the earlier scenes, for narrative continuity and the shortened ‘churchyard’ scene in Act V that dealt with the inconsistencies of social norms and laws.

Divya Dev towers—literally and figuratively—over the rest of the cast with his brutal engagement with Hamlet’s confrontations with his own subconscious and the outer world. Clothed as a Buddhist monk and adequately shorn, Divya Dev brings the play its rare moments of glory, and unfortunately spotlights the production’s need for proper pacing. For it is indeed unfortunate that Hamlet’s monologues sounded hurried and less felt than more redundant moments like Ophelia’s breakdown. The play is after all about Hamlet and not Ophelia’s gendered interpretation. Which brings me to the next stellar performer, an unlikely but very lively Shristi Shrestha as Ojaswi or Ophelia. She carried herself with grace and lovable impunity throughout. I remember writing last year about the Globe Theatre production, ‘Phoebe Filoes’ Ophelia came across as strangely apt in her raw, youthful energy and awkward insanity’. Shristi Shrestha actually lives up to this accolade.

Like the sculptural piece I talked about earlier, Nepal’s interpretation of Hamlet strung together wonderfully crafted moments or blocks in time to build an edifice that speaks for the cast’s commitment if not the finesse of the overall production. I felt somewhat deflated by Aruna Karki’s brilliantly played but insular Gertrude/Gyaneshwori—as a mother of an adolescent son myself, I did not quite empathise with her self-absorption. A trait that seemed to beset most of the actors, whose craft was otherwise brilliant. It seemed as if they had rehearsed their roles to perfection in the seclusion of their own spaces and not quite learned how to respond to each other. Hamlet as a play is in fact well known for this trap, as I have already said even ‘earlier in the season, the play opened at Barbican in London with Benedict Cumberbatch of Sherlock fame in the lead. The actor had been critiqued for his distantiation from the rest of the cast and action.’ It is warning we should heed. Some texts are like quick sands and can easily engulf a perfectly brilliant cast. For Kamal Bikram did play Claudius to perfection but again fluid in the same insularity. Rajkumar Pudasaini comes across as wasted in his Ghost and other roles given his gestural acumen but his casting no doubt reflects more upon directorial acumen. Lord Polonius played by Bholaraj Sapkota did not leave a mark, neither did Horatio played by Shrawan Rana till his last monologue when he steals the show. Rarely have I witnessed a stronger recuperation by an actor, almost like four sixers in a game of cricket in the last over!

Sujan Oli’s lights were adequate and added little more than expected. The craft of stage production fell lower than what I would expect of Theatre Village but this is a show not to be missed for it will be showing and in Nepali in London next

month. I do hope we will see some resonances of Nepal in the Burning Man experience this year!

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)