Entertainment

Bringing stories to life through theatre

In modern theatre, everyone is a stranger. I liked the intimacy I witnessed in cultural shows when living in Nepal. So the design of playback theatre is small audiences in community settings. And we tried to recreate a little of that kind of intimacy

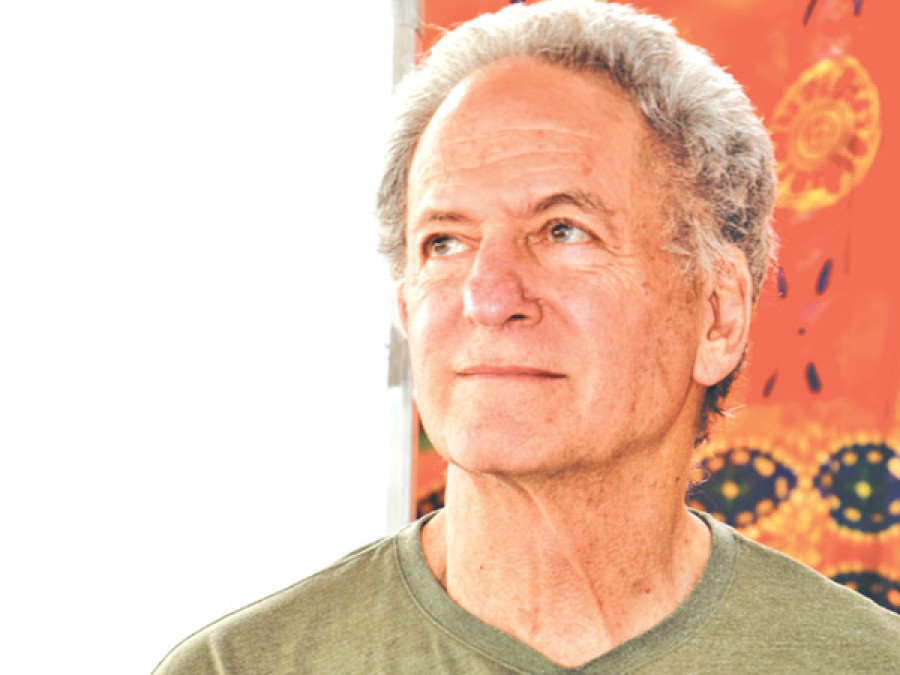

Playback theatre is an original form of improvisational theatre in which the audience contribute stories from their lives, choose the actors to play the different roles, and witness their stories come to life, as they are adapted theatrically on the spot. Performances are a joint effort of a team of actors, a musician and a conductor whose role is to converse with the audience and to engage them in dialogue. In the absence of a predetermined script or a score, playback theatre relies on voluntary contributions from the audience promoting the right for any voice to be heard, orchestrating intimate exchange, and allowing for catharsis through drama. What has today expanded into a medium for activism, justice, and education was originally a concept conceived by Jonathan Fox and Jo Salas. In an interview with the Post’s Kripa Shrestha, Jonathan Fox shares the origins of playback theatre and how his experience as a Peace Corps volunteer in Nepal in the 1960’s influenced the birth of its concept. Excerpts:

What was the original concept behind playback theatre?

The idea for playback theatre came from an image I had. It was an image of an audience, a stage and actors sitting, facing the audience. And the stage had a warm colour, and I knew that the actors who were there would act out the real stories of those people. So, that was the basic idea. I was already involved in experimental theatre but this was a little bit different. It was improvisation. But it was very personal, and was also very intimate. I didn’t know what it might lead to; I didn’t know if it would work—but I knew I wanted to try.

Having co-founded playback theatre with your wife, Jo Salas, could you shed light on what’s it like working together?

Of course, it’s a challenge to have your work life and your personal life so integrated because it’s hard to keep them separate sometimes. But it’s also very satisfying when you can both join your creativity with someone else, but also complement your strengths and your weaknesses. It can’t be done without being in good communication with each other— and that’s a constant effort. But it’s now forty years later, and we’re still together and we’re still doing it.

What was the reception like when you first introduced playback theatre?

Well, I would say that in many ways, the reception was reluctant. Or, it wasn’t received so easily or so well. For example, government art councils said that, “This isn’t theatre. We can’t read the script. It’s too process-oriented.” Various agencies and organisations said that this is too psychologically dangerous or too emotional. On all sides, people said this is not good. And yet, from the beginning, people raised their hands and they told stories and they seemed to be very pleased and satisfied when they saw us act out the stories. So it worked with audiences, even though our skills were not so great because we had to build it up; we had to learn what to do; we had to learn many things about it. So at the beginning, it was very, very crude. Yet, even from the beginning, people would say, “I have something to tell.” It’s an individual who tells his or her stories, yet what’s amazing is that when you do an evening of performances, the stories are so connected. This means that people are unconsciously listening to and responding to each other. It took us a long time to really appreciate this. But people have a dialogue through their stories. I think we learned how to do this very, very early in our human existence. And now in many ways, in modern life, we’ve forgotten. So playback theatre is a way to reconnect with certain ancient ways of communicating that I believe people need.

Could you elaborate on how your experience as a Peace Corps volunteer in Nepal was a source of inspiration that eventually led to the birth of playback theatre?

Sure. I think the most important part is living close to nature. So when you’re in a village in Nepal, you live so close to nature and everything that happens, happens in relationship to nature—the weather, the animals, the cycle of the seasons, the crops. And you have to adapt to the conditions. So most theatre creates the conditions for the audience; they create an artificial atmosphere. But our theatre is the opposite. We go into the community—it may be a school, it may be an organisation, it may be a community centre, and we have to attune or adapt to what’s there. This element of attunement, of connection, was I think the most important thing. And it’s something I didn’t learn while growing up in New York City. Another thing I would like to mention is, because I was living in a small village, when there was a cultural show or dance or some kind of cultural activity, it took place in a very, very intimate setting where the dancers would dance in something that was traditional but, of course, everyone knew them and they knew everybody. And so you can do your performance on two or three levels at the same time, and they weren’t strangers to each other. In modern theatre, everyone is a stranger. And I liked the intimacy I witnessed in cultural shows in Nepal. So the design of playback theatre is small audiences in community settings. And we tried to recreate a little of that kind of intimacy even though it’s in a modern context.

Can you tell me about your experience volunteering in Nepal as a Peace Corps?

I was sent to Nepal in 1968 for two years to work in agriculture, to help Nepali farmers begin to use modern methods of agriculture like improved seeds, fertilisers and insecticide. Of course, I knew nothing about this. So, this was awkward, to say the least. And at that time, in Nawalparasi district, where I was, the fertiliser, the insecticide, and the seeds never got there. So I actually had very little to do and I don’t think I gave very much or taught very much. But I learned so much.

What brings you to Nepal again after nearly fifty years?

What brings me to Nepal is theatre work. Playback theatre is now being practiced in Nepal. And one of the projects based on playback theatre invited me to come and teach the practitioners. So I was able to come back to Nepal actually doing the work that I love to do. And it’s so exciting to me that it’s being used in Nepal by Nepalis in a project that I think is important. So it’s been wonderful.

Given the application of playback theatre in political activism for human rights and education, how do you see it fitting into Nepal at present?

Storytelling can be very powerful. The extent to which playback theatre invites everyone’s stories, not just the big shots but the little people as well, and invites people to listen to each other in a way that seems to work somehow because of the theatre part, because it’s not just talking. Embodying the story with music and drama somehow creates a context where people become engaged. So my hope would be that playback theatre can play a positive role in Nepal especially after years of conflict so that people can appreciate each other.

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu