Entertainment

I Have to Feed Myself, My Family and My Country

In 2013, the young, protean, conceptually sophisticated artist Hit Man Gurung started work on a piece titled Kumai Went to Arab, which was the beginning of a powerful, emotionally hard-hitting series of paintings

Sophia Pande

In 2013, the young, protean, conceptually sophisticated artist Hit Man Gurung started work on a piece titled Kumai Went to Arab, which was the beginning of a powerful, emotionally hard-hitting series of paintings, installations, and collages that is titled I Have to Feed Myself, My Family and My Country.

The title words encapsulate a powerful sentiment that both comments on and is an indictment of the current situation of Nepali workers living abroad in the Gulf countries, Malaysia, Indonesia or elsewhere, where they are at risk of the kind of exploitation and careless treatment of human life that is both illegal and absolutely ought not exist in the 21st Century.

Hit Man’s two latest pieces for the series have been selected for the 8th Asia Pacific Triennial (APT8)—a prestigious art event held every three years in Australia to highlight

the works of contemporary artists from Asia, the Pacific region and Australia. The selection precipitated the four-day-long show that was held this past week at the Siddhartha Art Gallery so that people would be able to see the series in its entirety before the selected works are shipped off to Australia.

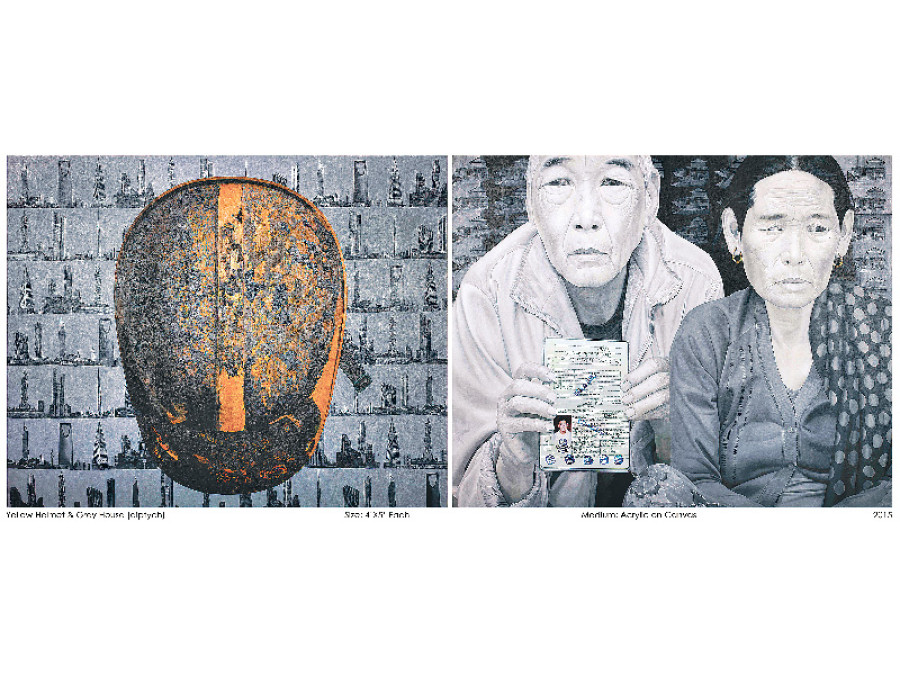

The first piece is titled Yellow Helmet & Gray House, a diptych on acrylic, which consists of two paintings that are 4ft by 5 ft each. The diptych portrays a yellow helmet against a grey pallet backdrop of famous skyscrapers in the Middle East juxtaposed next to a photorealistic portrait (very much Hit Man’s style of painting) of an elderly Nepali couple holding up the passport of their son, Raju Gurung, who was found dead wearing a yellow helmet in the cement factory he had been working in—the victim of an industrial accident that took his life six months after he left Nepal to try and earn a living to support his aging, increasingly feeble parents.

Behind the couple is another grey background, this time depicting iterations of the house that they were able to build (previously they had lived above their cowshed) with the insurance money they received.

The second piece is another large congruous two-panel canvas titled 9:11 am—the ominous corresponding time in Qatar when the earthquake hit at 11:56 am Nepal time on April 25. An equally searing piece counterpart, this painting shows a man (a self portrait of Hit Man himself actually, another signature of his personal style) holding a football with the words “Bidding Nation Qatar” written on it. The man’s face is covered in drops of sweat, he wears a yellow safety helmet, his eyes are red, behind him is a canvas print backdrop of the houses that have been shattered in the earthquake in Nepal, and the message is clear: our Nepali workers were forced to remain in the Middle East to build stadiums, not allowed to return home to rebuild their own destroyed houses, and they were forced into that situation because they DO have to feed themselves and their families; without the remittance they send home, the country wouldn’t stay afloat.

Hit Man is an artist with a social and political conscience that is focused on a subject that haunts us all: the existing situation of our fellow compatriots who migrate to other countries in search of work. His art is not the kind that you hang in your house; you could not look at it without flinching.

This kind of art is a clear-eyed, almost forensic examination of a human situation that involves research, detective work (Hit Man and his friends needed to sift through massive amounts of paperwork to find Raju’s parents in their Lamjung village) and finally, a great deal of thought regarding the medium that will best represent the message.

Hit Man’s methods and modes of execution involve a wealth of minute details. In his striking, heart-wrenching 5ft by 6ft acrylic and multimedia work Mom Has Tragic Story, a Nepali woman holds a coffin in her lap, an iconic reference to the ‘Pietà’— a well-known subject in Christian art perhaps most famously realised in a sculpture by Michelangelo of the Virgin Mary holding her dead son in her lap. In Hit Man’s interpretation, the coffin is a symbol for the three bodies that arrive on average per day from the Middle East. The bereaved but stoic woman is surrounded by real life photos of visa applicants that the artist has painstakingly collected along with letters written by these very migrants.

Another piece titled Every Day At The Airport is a real coffin—one that actually brought back the body of a man who died in the Middle East. Measuring 6ft by 4ft by 1ft, the coffin, covered with copies of migrant’s passports, is an authentic artifact and a gruesome reminder of the worst outcome of mistreatment at the hands of the criminally negligent and willfully cruel.

An exhibition like this is more than just a show of artistic skill; it is an indicator of a shift in our society, spurred by outspoken thinkers, towards understanding (forcefully so) the dire realities of the people who suffer on a daily basis but have thus far been largely ignored by their very own government —one that extorts the very labour class upon which it depends to keep their ugly realpolitik alive and thriving as they turn their faces away from the people they are duty-bound to defend.

4.91°C Kathmandu

4.91°C Kathmandu