Entertainment

Birendra Pratap Singh A Master Artist

Singh’s skill in his preferred medium of pen and ink is apparent in the range of his work available for everyone to see, for a month, at the Nepal Art Council in Babarmahal

Sophia Pande

Yet the term “Master” can certainly apply to artists of our time, particularly, again, if we look at certain people through the traditional lens of art history, which insists on placing artists and their works in context with the times in which they are working, and also, of course, granting them this title based purely on their skill.

My argument is fairly simple, in the trajectory of the Nepali history of art, and considering contemporary artists working today, there are a few undeniable masters, among whom, Birendra Pratap Singh, in light of his current retrospective, now firmly holds a place.

Singh’s skill in his preferred medium of pen and ink is apparent in the range of his work available for everyone to see, for a month, at the Nepal Art Council in Babarmahal. The man is able, just as Raphael or Titian were, to convey forms, animate or inanimate, with just a few strokes of the pen, making the sureness of his hand and the alertness of his eyes apparent in his diverse drawings.

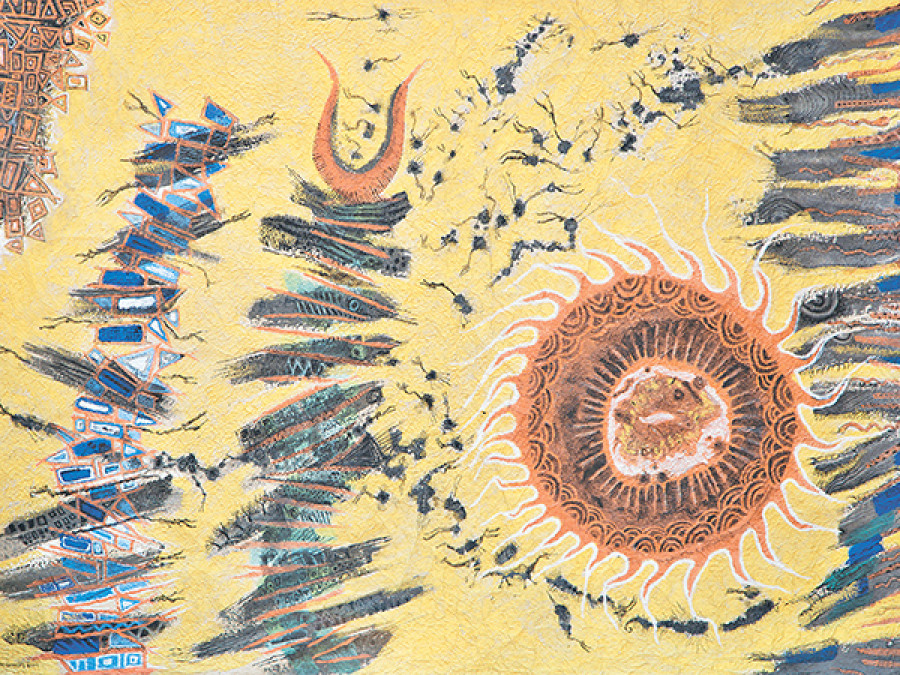

Even while Birendra Pratap Singh’s drawings may vary from the surreal to the quirkily figurative, his ability to delineate whatever he wants exactly as he pleases is apparent in each of the drawings on display. In the more cryptic drawings you can see the evidence of pure psychic automatism—a phrase the artist has coined himself, for his method of putting pen to paper and producing whatever forms his brain desires. These drawings are markedly bizarre, but, to my mind, as powerful as his more famous works, such as the pen-and-ink drawings of cultural heritage sites, in their rawness and their ability to convey a man’s innermost imagination.

The retrospective itself, which I have written about before from a curatorial perspective, is markedly different in its method of display. The linear structure that marks most such shows is absent. Instead, for the most part, the curators have put together Singh’s work in aesthetically pleasing groups as well as in themes that complement each other.

The grouping together of Electrocardiogram, a series of mixed-media works, from an underseen exhibition at the Kathmandu Contemporary Arts Center (KCAC) in 2010, is a rich example of the amalgamation of Singh’s virtuoso subliminal technique melding with his thought processes, resulting in a complex disturbing series on how disease affects the human body and mind. The series was inspired by a heart attack that Singh’s elder brother suffered around that time.

There are many ways of interpreting the more confounding works of highly skilled artists. We can look for clues in their lives. Hence the clever, essential timeline at the entrance to the retrospective that depicts major events in Singh’s life simultaneously with the evolution of the history of art in Nepal over the course of those years.

Viewers can, therefore, glean what they can from some of Singh’s works, either interpreting them from the timeline, or just from the expressionism of the pieces themselves, most of which, the artist freely states, have some connection to the environment, both natural and artificial—a subject he returns to time and again.

This retrospective may be mysterious to the layperson; there is not a lot of explication, yet I doubt that any one would walk away without a measure of awe. Above all, though, the show is most significant because it highlights the lifeworks of a man who, even at the age of 15, would walk all over the Valley to visit the other masters like Manuj Babu Mishra, Shashi Shah, and Ratan Rai. These men were in their twenties at the time, but more solvent than a poor aspiring teenager, and willing to lend their minds, their books and their conversation to a thirsting brain.

The story of Birendra Pratap Singh is ongoing, this exhibition provides us with the chance to see the breadth of his works and to appreciate a certain kind of genius in real time instead of posthumously, which happens in the case of most old masters. Let us be grateful for this opportunity.

22.05°C Kathmandu

22.05°C Kathmandu