Entertainment

A Defense of The Freedom of Expression

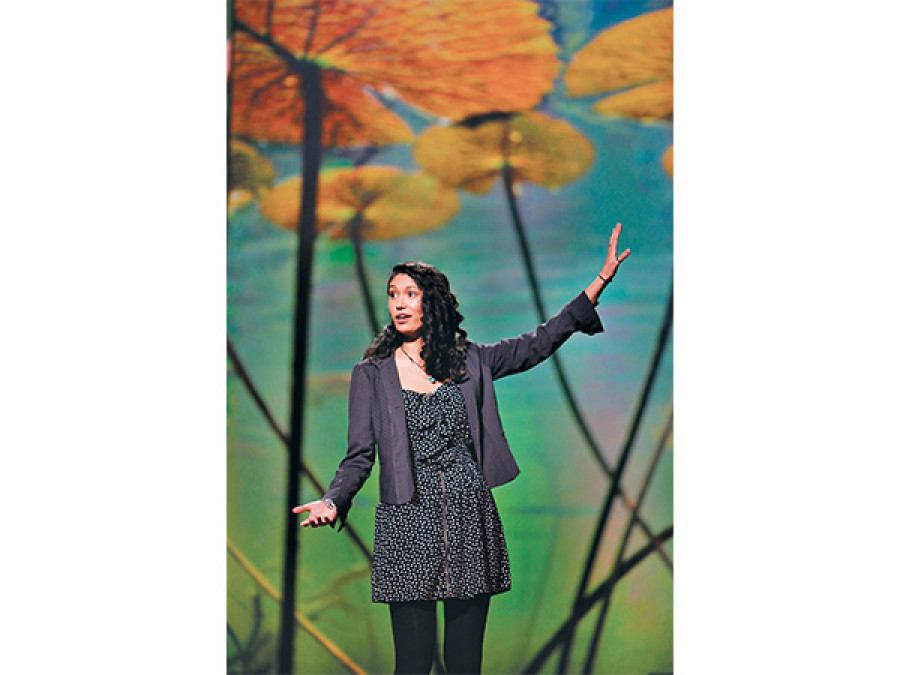

Last month, on December 27, a young American poet named Sarah Kay filled out around 700 seats at the Alliance Française in Kathmandu.

Sophia Pande

Accompanying Kaye were a few of Nepal’s own spoken word aficionados, members of the Word Warriors: Nayan Pokhrel, Ujjwala Maharjan, Samip Dhungel, Gaurav Subba and Yukta Bajracharya, all young, most reciting in their native Nepali language, dealing with issues like their love for this city, sexual harassment, and parental expectations.

Writing good poetry (if you can’t write poetry, you most certainly can’t write spoken word) is exceedingly difficult, and performing it out loud is possibly even more challenging; so the fact that these artists had their audience riveted is a testament to their talent, and also to their bravery, because poetry is a bonafide art form, sure, but to speak out as a Nepali woman about certain injustices still requires pure guts.

The reason why spoken word in Nepal and the world over is such a resounding success is that it allows for people to rant, at establishments, at people, at life’s bigger and smaller unkindnesses. Sarah Kaye’s main impact that day, at least in my mind, was revealing, albeit very charmingly, the idea that almost any thing can be turned into art, so don’t be afraid to express yourself, no matter how daunting the potential response. Perhaps this kind of thinking is considered a given in liberal circles in the Western world, but here in Nepal, where we still say “Didi” and “Bhai” to strangers and are often more wont to swallow our words rather than possibly insult either an elder (or anybody really), it is a refreshing breath of air to see people unafraid to express their views on controversial subjects.

My point is this: in a world where everyone is currently talking about the targeted, cold-blooded assassinations of those satirists who worked at the weekly French newspaper Charlie Hebdo in Paris, killed for their often times incredibly politically incorrect cartoons, is there a line to be drawn?

Everyone I know, and possibly every writer on the planet has now published their views on this subject. Friends and public intellectuals have ranged from being furious at the perceived homophobia and Islamophobia of the Charlie Hebdo founders and staff, to being confused as to whether freedom of speech ought to include the right to extreme views, satirically represented or not.

Personally, to be honest, I was a bit confused too. Normally, in instances such as these, if you are really a liberal, you stand on the side of freedom of speech no matter what because you believe that once establishments take it upon themselves to curtail this inarguable democratic tenet, then where does that kind of censorship end, right?

Well, yes. But, as Teju Cole argues in his incredibly well thought out piece in the New Yorker magazine today, one can continue to support the freedom of speech and still acknowledge that some of it can be incredibly ugly.

I leave it up to you to decide if you find some (or most) of the Charlie Hebdo cartoons offensive, or perhaps shocking but still funny. The point is, you must decide for yourselves. Just as long as you don’t think that being insulted entitles you to pick up a gun and kill the people you are angry with.

This is an important discussion the world over, especially right now in Nepal, where we are even now drafting a constitution that ought to represent all these democratic values (some values are inarguably democratic wherever they originated from). So now is the time for people to start speaking out, to read different viewpoints and try to understand for oneself, what you think is “right” and “wrong” without resorting to violence and ugliness. Otherwise, we will be relegating ourselves to a pre-conflict era Nepal where it would be impossible to imagine a woman like Ujjwala Maharjan standing up on stage and giving the world her middle finger.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu