Culture & Lifestyle

You’re all right, Mr Mukhiya

Tek Bir Mukihya, the man behind Sajha Prakashan’s iconic book covers, is the Nepali arts’ unrecognised hero whose experimental approaches were ahead of their times.

Urza Acharya

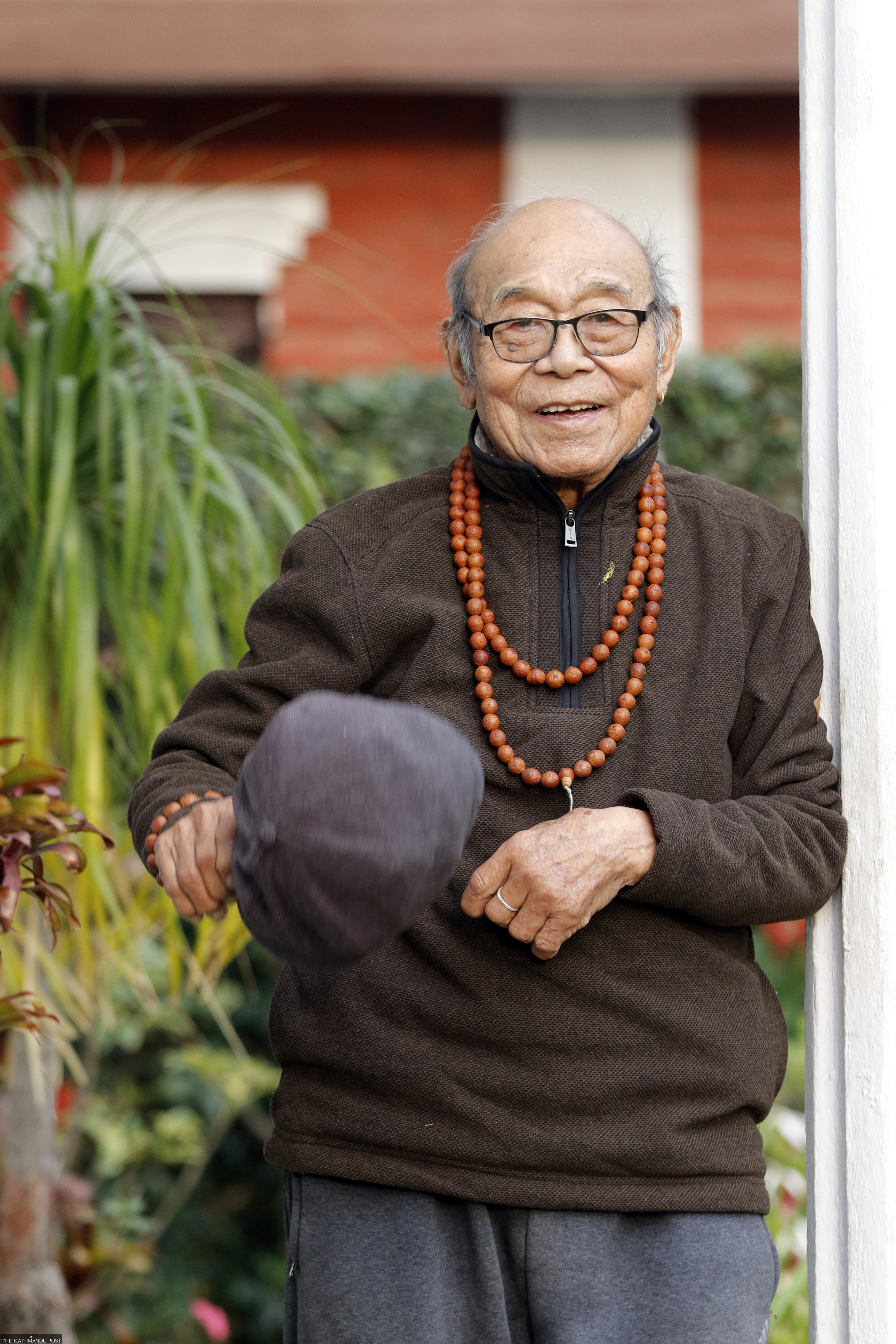

Even at 90, Tek Bir Mukhiya is going strong. “Look, I still have all of my teeth,” he says. Surprisingly, he does. Strong ones too. We are seated in the living room of his house in Bhaisepati. It is a beautiful room adorned with paintings by Mr Mukhiya and his son, Samridh. “I’m hard of hearing. You’ll have to be louder,” he tells me. “Is this okay?” I speak louder and louder till he gives me a pleasant nod.

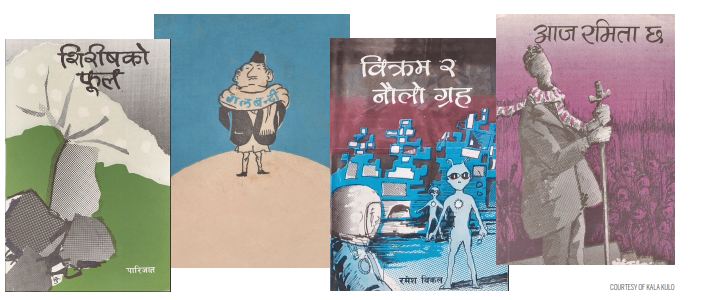

Tek Bir Mukhiya was the chief artist for Sajha Prakashan for several decades, from the late 60s to the 2000s. The iconic cover designs of old Sajha books—some abstract, others surreal—were all born out of the mind of one individual: Mukhiya ji. If you look closely, the covers of Sajha’s publications of Parijat’s ‘Sirish Ko Phool’, Ramesh Bikal’s ‘Bikram Ra Naulo Graha’, BP Koirala’s ‘Doshi Chashma’ and ‘Sumnima’, they all have a mysterious ‘Mu’ written somewhere, like a fun little easter egg. That’s him. An individual that shaped the very course of Nepal’s literary and art history but is yet not very known to the populace.

Humble beginnings

Getting information out of a 90 year-old-man is not an easy task. But still, Mr Mukhiya was kind enough to indulge my constant barrages of questions and his wife, Shukra, was kind enough to feed me tea on a rainy April noon. Born in Kurseong in Darjeeling, not much is known about Mr Mukhiya’s childhood except that his ancestors moved to India from Okhaldhunga.

“From the anecdotes he’s told me, I think he was very mischievous as a child,” says his son Samridh. Mr Mukhiya tells me he once had a pet monkey as a child. “One day, the monkey bit my sister, and my father gave it away to a monk,” says Mr Mukhiya. There’s no way to fact-check this, but somehow, I believe him. Because from what I can piece together, he was an eccentric man. A lover of cinema (pulp ones at that), photography, books and philosophy, Mr Mukhiya pursued unusual interests—some seven or eight decades ago. He shows me a collage of black and white photographs, and in all 20 photos, he’s making silly faces. In today’s Snapchat filters era, it’s commonplace. But back then, it must’ve been pretty cool.

At some point in his childhood, he came to Calcutta with nothing. “My father used to sell whatever drawings he made to make enough money to watch a film,” says Samridh. “But what exactly happened in Calcutta is a mystery. We only know what he wants us to know.”

Sometime around 1965, Mr Mukhiya finally came to Kathmandu. His contemporaries include writers Bijaya Bahadur Malla and Ram Kumar Panday and artists Kiran Manandhar and Lain Singh Bangdel. He shows me photographs with several known figures, even writer and playwright Bal Krishna Sama. The photos prove that Mr Mukhiya was a part of the growing art circle of the past, rubbing shoulders with some of the biggest names in Nepali art history. This begs the question, why isn’t his name as well known as the others?

Sajha Prakashan days

The answer may lie within the office space of Sajha Prakashan in Pulchowk, Lalitpur. At some point in the late 60s, Mr Mukhiya took up a job at one of Nepal’s oldest publication houses. His job was to come up with cover designs that best suited the book—be it fiction or non-fiction. “I used to read the book entirely before starting the cover,” he says. “Nobody, not even the writer, could tell me what to draw.” Mr Mukhiya says this with conviction. He clearly enjoyed autonomy with his book covers. This is possibly one of the reasons why his cover designs are so attractive. They hint at the story but can stand alone like full, complete pieces of art. One particular cover for a book called ‘Galbandi’ features a man dressed in daura-suruwal and dhaka topi. There’s also a shawl wrapped around his neck, with the words ‘Galbandi’ written inside it. It’s so simple yet sophisticated. Other cover designs by him are more complex and abstract in nature but carry a lot of depth and foreshadowing.

I reached out to Hom Nath Bhattarai, a senior officer at Sajha Prakashan. His voice lit up when I asked him about Mr Mukhiya. “Mukhiya dai was a gem; it’s rare to find people like him,” he says. “Once he started working, he would forget himself. Hot water would turn cold, but he never stopped.” Bhattarai reckons he designed covers of over 6600 for Sajha. The staff, at least those who remain, remember him as a simple man—he never smoked or drank and came to the office every day on his bicycle until his retirement in 2009.

Kala Kulo, an art initiative, has taken up the project of archiving and researching his cover designs, mainly from the 60s to the 80s. When asked about why they chose to archive Mr Mukhiya’s work, Kala Kulo member Dipti Serchan reveals that the “self-taught nature of his work” as well as “the experimental and creative practices he displayed at the time” are what drew the team to him.

“We also wanted to subvert the notion of what high art is and show through Mr Mukhiya’s book cover that even within a more institutionalised setting, an artist was experimenting and practising his craft,” she says. Unlike his peers who were busy doing just ‘art’—painting or sculpting, he was fully employed in Sajha, churning out one cover after another. His image grew more as a graphic designer than an artist. This was both rewarding yet limiting. Yes, it proved to be a stable source of income, but at the same time, it boxed him inside the ‘designer’ tag.

At Sajha, Mr Mukhiya experimented with collages, woodcuts, block plates, zinc plates and even dot matrix printmaking. Despite limitations in technology and colours, Mr Mukhiya tried out and eventually mastered working with colour gradients to create a unique set of cover designs every single time. This creative labour and willingness to stray away from conventional art standards of the time placed him as an auteur ahead of his time. But because his most well-known works are his book covers (and not ‘high-art’), Mr Mukhiya never got due credit.

Mukhiya, the artist

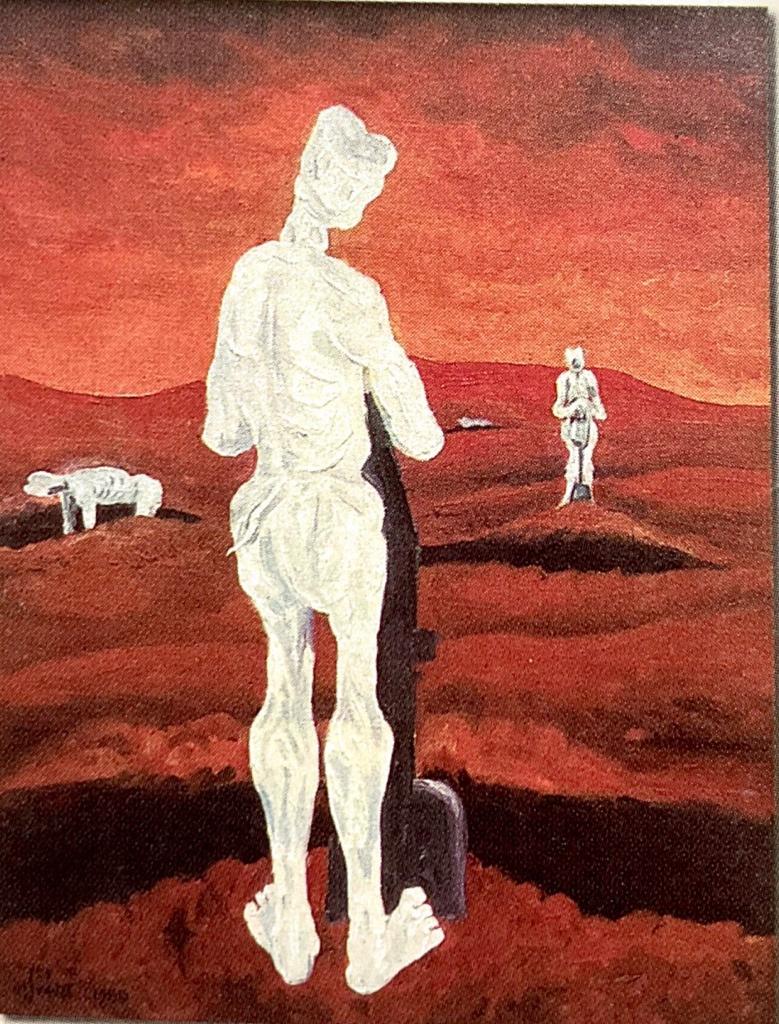

But Mr Mukhiya isn’t a remorseful man. “My father was too kind for his good,” says Samridh. Besides working on covers, Mr Mukhiya also painted—landscapes, portraits, you name it. He also participated in several exhibitions by the Nepal Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), the 1981 Asian Art Biennale in Bangladesh, and the 1980 Contemporary Asian Art Show-Fukuoka Art Museum in Japan, among others. There’s no way to bracket him as one type of artist—there’s dynamism in his works. Some are still life; kids playing outside and a mother carrying her child, while others are impressionistic scapes of various regions of Nepal, mainly Khokana. Some are symbolic—abstract figures of gods from all religions dance about on the canvas, while others are bound to realism. And he sold a lot of these paintings.“The good ones are all gone. He was too generous with them,” says his wife.

According to Samridh, at one point in his career, Mr Mukhiya also had to make a choice between painting what he truly wanted vs painting what would sell. “Though my father was a sole earner, we never felt deprived of anything,” he remembers. People would commission portraits, and religious paintings, which Mr Mukhiya created diligently. But in between, there were moments of introspection. Especially his moody self-portraits, which his son is fascinated by, lend a window into his psyche—their dim colours and his sullen look perhaps hint towards the turmoils inside. But these are simply speculations, as Mr Mukhiya was never one to verbalise.

In his paintings, he also displayed a sophisticated understanding of styles and colours. If the subjects in his painting are suffering, like one where he painted a man sitting beside the rubbles of his house, the palette carries weight; it has a sense of gloom. Mr Mukhiya was also extremely well-read; he had books on Dali and Monet in his library. Moreover, his frequent travels to Japan—as a cartoonist—influenced him as he mingled with artists from all over the world.

His legacy

In all fairness, Mr Mukhiya isn’t necessarily an unknown figure. He won the order of Prabal Gorkha Dakshin Bahu in 1981 and has painted countless paintings and designed logos for the Nepal government (like Aayo Nun), some credited while others not. In 2020, Tek Bir Mukhiya was asked to design a badge for parliament members. “He was given very little time to come up with the badge, but he did it anyway,” says his wife. “But they approved the draft without consulting him, which led to the fiasco.” The badges were ridiculed for being tacky and flawed. This was the first time Mr Mukhiya’s name was brought negatively into the limelight. But this incident reflected the government’s incompetency rather than question Mr Mukhiya’s prowess.

“You should call him ‘the king of book covers’,” says Bhattarai, reflecting on the sheer volume of cover designs he produced over this lifetime. But the book covers only scratch the surface of what Mr Mukhiya is. Listening to anecdotes from his family, co-workers and others, one can see that he was an incredibly hardworking, kind-hearted, thoughtful and, at times, even an eccentric man whose goal wasn’t fame or money but the tireless pursuit of perfection in his field.

Mr Mukhiya still paints. His current muse is the Pashupati Temple which he has been drawing over and over again. The lines are still sharp, and the colours still blend. Though he’s a little forgetful now, he’ll tell you an anecdote from his younger days in great detail. He’ll show you a metal stamp he made of his face. There’s still an aura of enigma around him. Even at 90, he’s all right.

17.56°C Kathmandu

17.56°C Kathmandu