Culture & Lifestyle

Chinese envoy to Nepal during the Cultural Revolution

In spite of Yang Gongsu’s role as the ambassador to three different countries, his role and experience in Nepal were particularly special.

Born and raised in turbulent times in China, Yang Gongsu, a local of Chongqing City, was originally named She Yizhe. He participated in the student movement during his early years of schooling and indulged in communist ideologies. When the anti-Japanese war broke, he worked underground in the 93rd Army of the Kuomintang, and then retreated to the headquarters of the Eighth Route Army in Taihang mountains as a secretary. Later in June 1941, he worked as a secretary to evade the investigation of the Kuomintang. Due to such circumstances, She Yizhe eventually borrowed the name of his old friend, Yang Gongsu, who disappeared during their schooling days, potentially due to political reasons.

She Yizhe knew his friend and his family well enough to answer any question he encountered in an interrogation. In November of the same year, he officially joined the Communist Party of China. While his friend, Yang, was never found, his other friend, Xu Chi, became a well-known contemporary reporter in China. He once wrote in an article: “She Yizhe has eloquence! He pays great attention to world affairs and talks about international relations, as if he was born with a global perspective, and his words are fascinating. He has a favorite phrase before starting any conversion: ‘So far as it is concerned’ [in English]. He always starts with this sentence, and then he talks endlessly. Everyone knew at that time that he would become a diplomat or an expert on international issues in the future.”

After the founding of New China, he decided to keep his borrowed name Yang Gongsu and engage in diplomatic work. Yang successively served as deputy director of Tianjin Foreign Affairs Office, director of the Foreign Affairs Division of the Tibet Autonomous Region Preparatory Committee, deputy director of the First Asian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Chinese ambassador to Nepal, Vietnam, and Greece, etc. He was among the first generation senior diplomats of our country.

Yang’s experience with Nepal from Tibet

In spite of his role as the ambassador to three different countries, his role and experience in Nepal was particularly special due to various aspects such as the political backdrop of the time and Cultural Revolution in China. Moreover, when Yang was appointed Chinese ambassador to Nepal in 1965, it was his first time abroad as an ambassador, but not the first time in Nepal. In 1956, he was a member of the Chinese government delegation to Nepal to negotiate and sign the Sino-Nepal agreement.

Yang was in charge of foreign affairs in Tibet and was in close and frequent contact with Nepal, and later in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he was in charge of dealing with Nepal. During the Sino-Nepali border issue settlement, Yang supervised the survey teams of the two sides during the boundary demarcation and setting up of boundary poles. As the person in charge of the Chinese border demarcation, he took care of the Nepali people in the upper bounds, not only technically (all materials and technologies needed for the border stumps were provided by the Chinese side) but also in terms of daily life. Yang recalls the difficult conditions of having to work in mountainous topography and confirms not taking advantage of the Nepali side and completing the task sincerely.

In order to help with construction in Nepal and resist the harsh conditions of aid from India and Western countries, China provided interest-free, low-interest, donated loans and projects to Nepal in accordance with the eight principles of China’s foreign aid at that time, and dispatched experts to help Nepal build small factories, such as tanning, brick and tile, etc., which could immediately be implemented, and also build roads for the Nepali side that foreign countries were unwilling to undertake.

With such ground-level experience, he was well informed and familiar with Nepal and China-Nepal relations, and was considered an expert on Nepali affairs at that time. He believed that the Central Government and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs must have taken these factors into consideration before appointing him the ambassador to Nepal.

Being the Chinese ambassador to Nepal

When he was appointed the ambassador to Nepal in 1965, Yang thought of himself as an ambassador not only from a friendly neighbor but also from a country having an extraordinary relationship with Nepal, and expected warmer, friendlier and a special treatment. However, that wasn’t exactly the case. He recalls internalizing that the king of Nepal cared about the image of the country’s sovereignty and avoided prioritizing any country over the other. Yang recalls King Mahendra as a “shrewd and capable king” who “was embraced by his people”. He wanted to win the support of China and other countries to fight Indian control, but his country had to rely on India at that time for reasons such as access to sea, transportation, economic support, etc. Yang admired King Mahendra’s policy of unity and balancing India at that time.

Any grand meeting attended by the king and queen would see the attendance of ambassadors of various countries. This type of meeting was ceremonial and carried out in accordance with the international priority practice. Priority indicated that regardless of the size of the country and the relationship with the host country, they will all be received in the order of the date of when the respective credentials were presented. Naturally, the Indian ambassador was the first in line as India was the earliest to send an ambassador to Nepal at that time and Yang was the last in order, but before other countries’ Chargé d’affaires or representatives of other international organizations.

When meeting the king and queen, each ambassador had about 10 minutes. Knowing well that he could not go against the diplomatic protocol and practice, Yang was downhearted when he was reminded of his time limit. Yang believed that being able to directly contact and talk to the king would not only enhance understanding and friendship, but was also extremely important in resolving major international relations issues. In an open and formal diplomatic setting, it is difficult to talk to the king long and so Yang was determined to find other ways.

The king used generals, who did not necessarily serve in the military but wore military uniforms, to associate with the ambassadors of various countries as a means of winning them over. One of the generals was in contact with the military attaché of the Chinese embassy and often visited as a guest. Yang soon became friends with him. He often set up small family banquets in his villa to invite some royal dignitaries, palace secretaries and others. At his home, Yang met the chief secretaries of the palace, and these men sometimes revealed a bit of the king’s thoughts and intentions, hinting at how foreign countries could cooperate with Nepal. The general also met the king’s second and third brothers, known as the second and third kings. The second king was also in charge of some royal affairs, while the third king was in charge of national sports and had married an American.

Sometimes the king and queen also attended private gatherings where they didn’t have to pay much attention to their royal etiquettes. Hence, they communicated with foreign dignitaries entirely in their personal capacity. The atmosphere was relaxed and lively, and the conversation ran free and extensive. The king was very concerned about the internal situation of China and the Communist Party, the international activities of the Party, and even more interested in China’s attitude towards some major international issues at that time. Yang recalls that the conversation between them was not between the king and the ambassador, but a small talk between friends, where exchanging views happened naturally, enhancing understanding, and promoting friendship.

On this occasion, Yang also met the current Crown Prince Birendra who was studying in the UK. He noted that Birendra was interested in China and immediately invited him to visit China. After returning from his China visit, Birendra hosted a special banquet for the diplomats of the Chinese embassy and talked about his impressions in China. Therefore, Birendra had contacts with China long before he became king.

Yang would specially invite the king, queen and important members of the royal family to visit the embassy to taste Chinese food. They ate Chinese food with much gusto. Yang was always mindful about the situation and avoided talking about serious topics, but the king sometimes asked about China’s attitude towards international affairs, especially the situation in Tibet. Yang also often entertained the Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Kriti Nidhi Bista. He recalls being pleasantly surprised with Bista's friendly gesture of allowing him direct access without having to go through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on important matters.

Cultural Revolution’s waves in Nepal

After the opening of the China-Nepal Highway, the Tibet Autonomous Region sent three entertainment troupes to Nepal to express congratulations and gratitude. This troupe was composed of Han and Tibetan youths, and brought the song and dance element of the “Cultural Revolution” and “extreme left” thoughts from back home. Yang first held an audition in the embassy, and invited the officials in charge of Nepal's diplomacy and culture to watch it. Yang requested them to review the show. After watching it, they praised the performance and approved the troupe to perform in Nepal. The only objection was that some programs, such as those opposing American imperialism and Indian reactionaries, were not suitable to be performed here.

Yang agreed and negotiated with the head of the troupe to adjust accordingly and they agreed. However, during the performance, they still shouted slogans in Tibetan language, which the Nepali officials and the public, and the foreigners who visited, including the Peace Corps of the United States, could not understand, so there was no dispute, but this practice of the troupe made Yang very dissatisfied. When they performed publicly in the square, Nepali and foreign tourists overcrowded the area. Yang intervened to shorten the performance and have the troupe return to Tibet as soon as possible. At this time, he recalls having realized that “the wave of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ in China was too great”, and Yang was completely powerless against the “Cultural Revolution” that came from China. In July 1967, Yang returned to China for medical treatment. After recovery, he participated in the “Cultural Revolution”. It was not until 1969 that Yang officially resigned as the Nepalese ambassador.

In 1982, Yang Gongsu, who was already in his seventies, voluntarily resigned from his post at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to recuperate. He spent his later years as an adjunct professor at Beijing Foreign Affairs University and the School of International Studies of Peking University teaching diplomatic history related courses, and tutoring graduate students.

In March 2015, Yang Gongsu passed away of illness in Beijing at the age of 105.

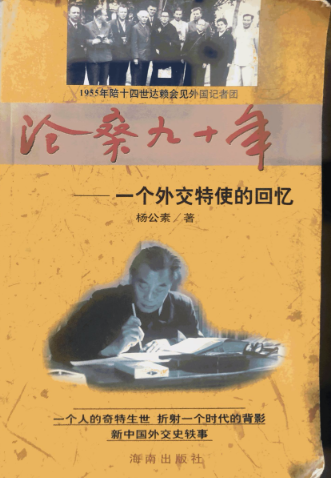

This piece is a translated compilation and condensation from selected chapters of Yang Gongsu's book, ‘Ninety Years of Vicissitudes: A Diplomatic Envoy’s Memoir’.

Pictures taken from the article ‘Forty years of diplomatic career, fulfilling the wish of serving the country all his life——Records of the first generation of senior diplomat Yang Gongsu’ [https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/4WrBoX9wvqVmz7lIqN_zuw]

Translated and compiled by Raunab Singh Khatri and Aneka Rebecca Rajbhandari for The Araniko Project

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)