Culture & Lifestyle

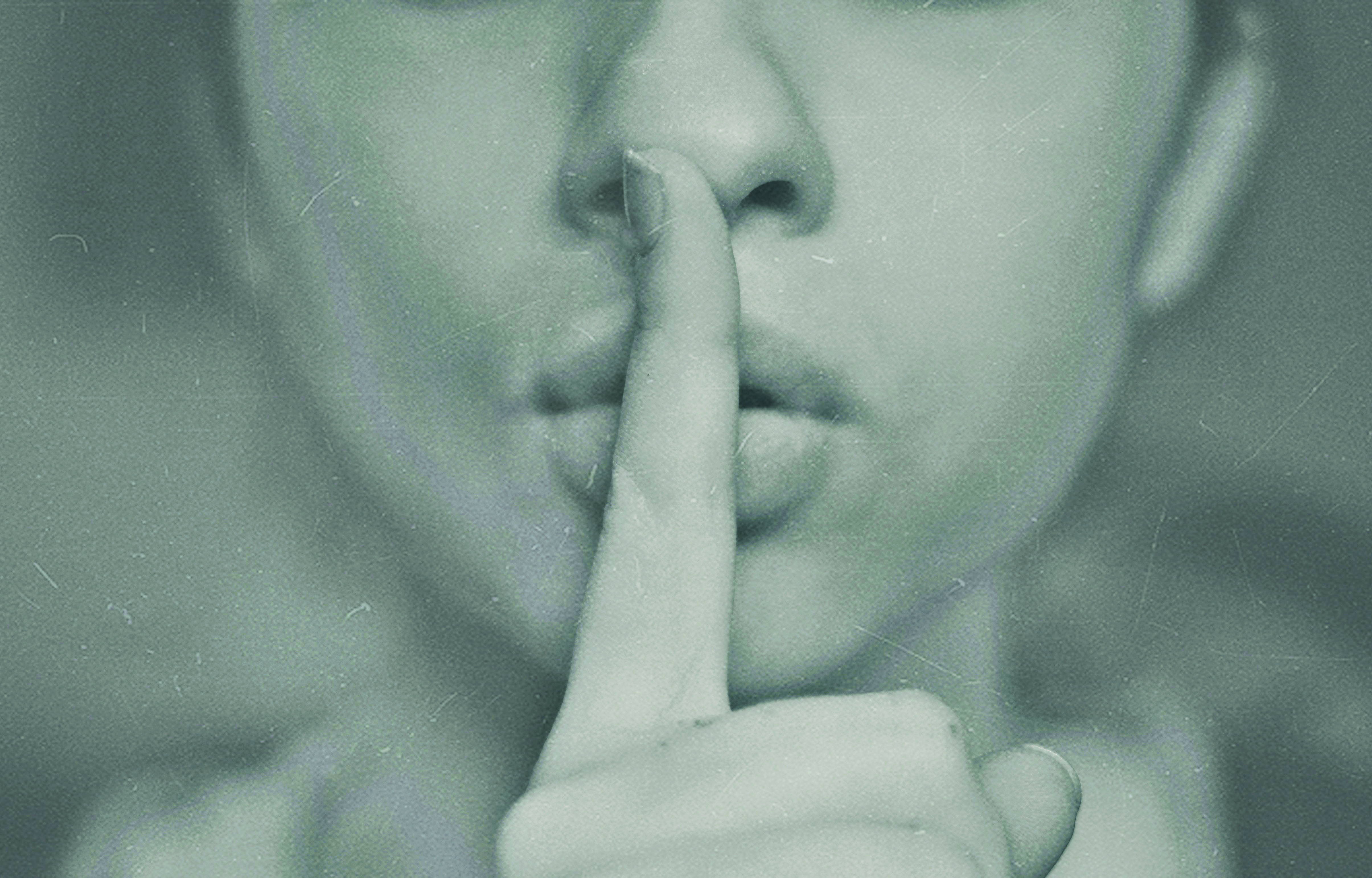

Still spoken in whispers: The obstacles of opening up about menstrual experiences

A woman’s menstrual cycle is the most normal reality of her life, but menstruation health and hygiene are still treated as a taboo subject.

Srizu Bajracharya

Rushed steps and hushed whispers are how Munu Maya Sherpa remembers most of her early period days as, in her village Baluwapatti Deupur, in Kavrepalanchok. Approaching puberty felt frightening and confusing, she says.

“I remember how I used to hurry down to the riverside to wash my menstrual clothing because we were told no one should see us washing or drying it. There were no sanitary pads in our days; we used old clothes and held the cloth together with our patuki, which we wrapped around our stomach,” says Sherpa, who works as a domestic helper in Lalitpur.

Sherpa stepped into puberty with little knowledge of why menstruation happens, she says, aside from her mother privately explaining to her that it was a sign she had become an adult and the monthly cycle would happen every month. “It was an uncomfortable subject to bring up among friends too,” she says.

Years later, it was her young daughter who introduced her to the how-tos of using a sanitary pad or absorbent clothing and the menstrual hygiene she should follow during periods.

But Sherpa is not the only woman who is uncomfortable speaking about her experiences of menstruation. She is not the only woman who has felt the need to cover menstrual pads in a piece of a newspaper when getting a packet from a medical shop. And she is not alone in feeling guilty, even ashamed, for going through her monthly cycle.

Although a woman’s menstruation cycle is the most normal reality of her life, society around her, just as she is, has remained mostly apprehensive and quiet about their vaginal bleeding every month. And as a consequence, speaking around menstruation has not been an easy and open conversation. This silenced culture has eminently contributed to how women see their natural cycle.

“Menstruation conversations still fluster people: it's awkward, uncomfortable and an experience people are reluctant to discuss,” says Durga Sapkota, a youth health advocate and co-founder of Youth-led Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights Advocacy Nepal.

“In urban settings, we find that women—to some extent—do talk about menstrual health although they have internalised the negative connotation of period related to purity and impurity, but in far off regions, women do not even know the basics of menstrual health and hygiene,” adds Sapkota, who works with adolescent girls, teaching them about menstrual health and hygiene, safe abortion, family planning while also talking about gender equality, domestic violence, and rape. Till date, Sapkota has provided training to 700 girls across Nepal.

Rashana Bajracharya, a 30-year-old artist based in Kathmandu, has also time and again found herself questioning her beliefs, although she has been vocal about menstruation and the woman’s body. In 2018, Bajracharya in an exhibition had displayed a huge canvas in the shape of a sanitary pad with red swashes and a three-headed woman surrounded with lotuses portrayed as a creator—the title of her artwork was ‘Purity of Impurity.’

“I wanted to question purity and put across the point that menstruation is the very cycle that makes a woman capable of procreating as people think menstruation is impure, but what is purer than the fact that she is the one creating the world,” she said. Bajracharya’s work boldly confronted the idea of purity and awkwardness surrounding the topic of menstruation.

“A lot of people might have felt uncomfortable when facing the artwork but the work felt significant to me because all our lives women are made to feel embarrassed and uncomfortable about their menstruation when it is nothing to be ashamed of,” she says.

“But even yet, I find myself barring myself from visiting temples during my period. If I do, then I think it will have a bad implication on my family. Such thinking has been ingrained in us," she says.

Radha Paudel, a menstrual rights activist and the author of ‘Dignified Menstruation is Everyone’s Business’, believes that one of the primary reasons the stigma of menstruation trails throughout the life of a woman is because a girl child, from the onset of puberty, is taught to believe something is wrong with her.

“She is denied her dignity, and made to feel anxious and insecure about herself right from her first period,” she says. “You have to understand that the way we treat a girl or a woman during her menstruation plays a vital role in the construction of power, affecting her self-esteem for the rest of her life,” she says.

Paudel has been at the forefront of the menstruation discourse, and she has been advocating for dignified menstruation before menstrual health and hygiene to break the silence around menstruation. “If we don’t talk about dignity first, we won’t be able to root out the idea of impurity that is entrenched in our culture. Moreover, when we miss out on talking about dignity in menstruation, the advocacy of health and hygiene will fail because the cleanliness it addresses will proliferate the belief that menstruation is impure and dirty.”

“So we need to create a society that is open to talking about menstruation—girls, boys, husbands, men everyone needs to be able to talk about it openly,” says Paudel.

Sapkota too affirms that men need to be part of the menstruation conversation because the stigma surrounding menstruation is rooted deep in the patriarchal system and for women to interrupt the system they need everyone’s support. “It takes everyone to bring a change in society—this isn’t just about women but a structure that obstructs dignity and equality,” she said.

According to Sapkota, most girls and women still don’t understand the term ‘mahinabari’, the Nepali term for menstruation, when talking about menstruation health and hygiene. “And the reason is the private discourse terms menstruation as ‘na chhune’; women and girls in families are taught they are untouchable and shouldn’t touch communal or cultural objects during their periods and that is the concept they carry around with themselves, making them more uncomfortable to talk about their menstrual experiences. The knowledge of menstruation instead of being an open education and reality becomes a private matter where no one knows if they are taking care of themselves in the right way,” she says.

This is true for Sherpa as well. No one really taught her or the women in her village the right way of taking care of themselves during their menstruation, she recalls. It was a hushed affair, where mothers or sisters taught their girls the best they knew about the monthly cycle. And tied deeply to the whispered teachings was the stigma attached to menstruation, where girls would be introduced to their blood as an impure experience that they must get through every month.

“They made it apparent that what I was going through was something embarrassing, unclean that needed rinsing off for purity,” says Sherpa, remembering the insights the women in the family shared discreetly with each other.

“The instructions that I was given were more about what we shouldn’t do during periods, like we shouldn’t go to religious places, we shouldn’t run too much, we should sit carefully. We were told to be cautious and not talk about it—that’s why it was ‘nachhune’,” said Sherpa.

It was the same for Kajal Jha from Janakpur. One of the foremost lessons she was taught by her sisters and mothers was to keep the experience to herself and avoid religious settings. “When I had my first period, I remember waking up to see my bed sheet covered with splotches of blood. I was scared and remember feeling embarrassed to ask my own mother what was wrong with me,” says Jha, who works with an international non-governmental organisation.

For Jha and many girls, menstruation was something they understood over time, with their own personal experiences. “It was more like a ‘learning-as-you-grow’ experience; no one really took the time to explain to us what exactly happened within our body, we learned about the premenstrual syndrome and period cramps when it happened,” says Jha. “The knowledge of the cycle was limited back in the day,” she says.

Most women are still unaware that the vaginal bleeding that occurs every month is the release of the uterus lining that prepares for pregnancy, says Sapkota. “They just know it is something that happens every month and it is to do with womanhood,” she says.

A few years back, Sapkota found herself shaken to the reality of how women saw and experienced their menstruation in Province 5 during one of her menstrual health and hygiene advocacy programmes. “The women there believed that undergarments themselves were a menstrual product used for periods. And many women shared it among themselves, and as a result, they all had gonorrhoea,” says Sapkota. “Menstruation hygiene still remains a big problem because we have not been able to open up discourse around menstruation: the problem is its education still remains a private issue.”

For women across the country, communicating about menstrual cramps or asking for leave due to menstrual pain is still awkward. “We may assume that in an educated setting, communication around menstruation would be easier, but sadly no one really understands what a woman goes through during her menstruation. Toilets will not have water or even dustbins and during urgency, there will be no menstrual pads, so the acceptance is only a deception. We have a long way to go,” says Jha.

And because conversations around menstruation, even among women, have not opened up, the challenges transman and intersex people go through is double, says Sudeep Gautam, a transmen activist.

“You wouldn’t expect a society who doesn’t understand women’s menstruation to understand what menstruating means for a transman. We as a society have not even come close to addressing our issues, from products related to menstruation to understanding our menstrual health, no one has really made an effort to think of what we go through,” says Gautam.

Gautam today has already had his ovary surgery meaning he no longer menstruates, however, the reality of menstruation for others in his community is still a hard-hitting reality that forces them to see that society has not accepted them.

“Even hospital caregivers don’t understand our problems when we tell them we have menstrual cramps. Although I don’t menstruate today, the awareness that transmen also menstruate is very minimal. And so it is difficult to reveal our problems as their prejudice is visible,” says Ghimire.

“If a trans man needs to change their menstrual pads they cannot use the women’s washroom, and then men’s restroom does not have the necessary privacy, or toilet commode, dust-bin or pads available. So, the discrimination starts right from asking for access to using one of the most basic human need,” he adds. “And I don’t know if we will ever reach that understanding any time soon with people still shying away from talking about menstruation.”

Moreover, menstruation discrimination is also tied deeply to violence and discrimination against women. “By excluding women’s natural menstrual experience, our society is giving men more power and creating environments where the men feel the privilege to ostracise women—and as a result, we inculcate a culture of violence against women and hinder women’s strength,” says Paudel.

Even though times are now changing, and menstruation-related awareness is picking up, there is still an impending fear that young girls will carry the insecurity and anxiousness of menstruation with them into their future.

“I hope when my three-year-old will have her menstruation, society will be more open. And I will make sure that she gets the necessary education to liberate herself from the negative thoughts that still hold us back,” says Jha. “But I am scared that she will learn that fear too, as change has been slow, and society is still not open.”

For Sherpa, however, despite knowing that menstruation is a natural process she has not been able to get rid of the idea of sin and purity related to menstruation. “The absurdity of it all is that the belief is now ingrained in me and perhaps in my daughter and sisters. Say what you may, I still am afraid that I will make the gods angry,” said Sherpa.

9.15°C Kathmandu

9.15°C Kathmandu