Culture & Lifestyle

Meet Dorje Dolma, the first female writer from Dolpo

Twenty-five years ago, Dorje Dolma was living in a remote village of Dolpo, battling a life-threatening disease. Now, she’s a speaker, artist, and one of the first people from Dolpo to write a memoir.

Ankit Khadgi

As the oldest of 11 siblings, Dorje Dolma spent most of her childhood taking care of her younger brothers and sisters as well as herding yaks and goats. This was in the early ’90s, when Dolpo had just started seeing visitors. Rich local city dwellers and foreign travel enthusiasts had started to travel hundreds of kilometres just to witness Dolpo’s pristine beauty, faraway in a corner in western Nepal.

While such changes were taking place for the country’s tourism industry, 10-year-old Dolma was deprived of basic health and educational facilities. She would also be defending her cattle against predators, like wolves and leopards, she says. Almost three decades on, not much has changed for the people of Dolpo.

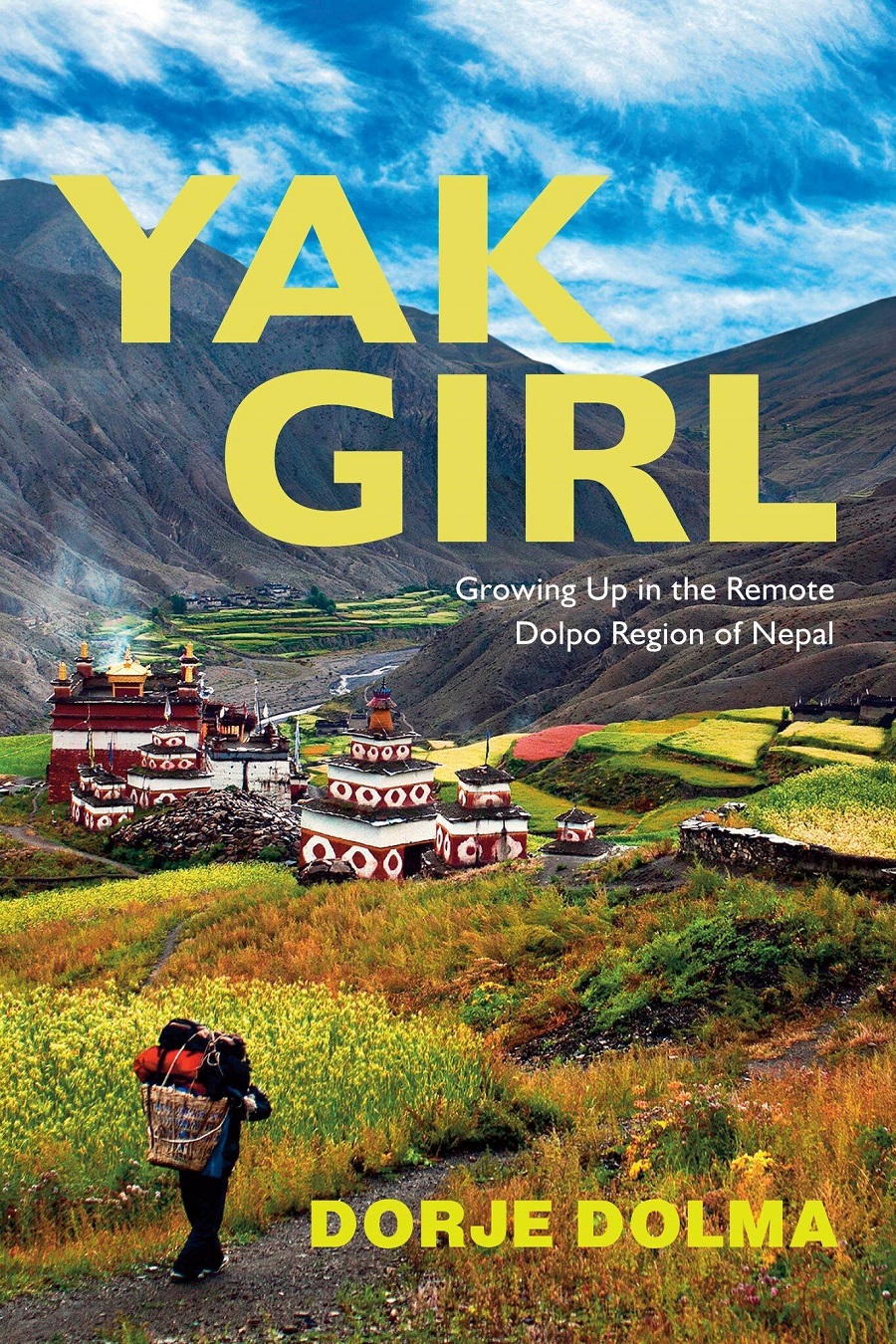

Recalling all her bitter-sweet childhood memories, Dolma, in 2018, published Yak: Girl, Growing up in the Remote Dolpo Region of Nepal, a memoir, which became the first-ever book written by a woman from Dolpo. The book talks about the first 10 years of Dolma’s life in her village, Karang.

“Although I was inspired by several factors, my main mission was to inspire and educate others about the unique Dolpo culture through my personal stories,” says Dolma, who’s currently living in Boulder, Colorado, working as an artist and a speaker

Living in a remote area, that too without any facilities, was tough for Dolma and her family. Neither did her village have a school, where she could enroll herself, nor were there any health clinics, which the locals could use when they were sick. The nearest health post would take weeks on foot to reach, she remembers.

“I lost five siblings and many relatives from simple illnesses, such as the common cold,” she says. However, regardless of their struggles, they kept on living their lives, doing their daily chores, which kept them busy all day.

While her parents would be occupied with growing food for the family, it was Dolma, who from the age of five, undertook the responsibility of taking care of the cattle, which she took to graze every day from morning to evening. While the cattle fed, she would keep herself busy, observing the mountains, the rivers, the clouds, which according to her, built the foundation of her creativity and imagination.

“I often was on my own in the mountains, up as high as 18,000 feet, surrounded by vast mountains, valleys, and rivers. I found it very mysterious being out in the middle of nowhere in complete silence, experiencing peace and freedom—just me and limitless nature,” she says.

Likewise, unlike the children of the town and urban areas, most children of Dolpo like her didn’t have the privilege to play with dolls. And that’s when she started using her imagination and played with rocks, stones, sticks, and created playthings from what was around her, which helped her develop an imaginative mind, which later became instrumental in pursuing nature art.

However, life changed for her when she was 10. Her mother detected a lump on Dolma’s back and after traveling for a month, when she reached Kathmandu, she was diagnosed with a life-threatening disease, severe scoliosis.

The treatment wasn’t economically viable for them as a family, as they lacked financial resources or any support. But fate had a different plan: an American family sponsored her treatment and took her to the US, where she had to undergo four operations for her spine.

But even after arriving in the land of opportunity, things weren’t easy for Dolma. “When I first arrived in America, I was embarrassed to wear my traditional clothes and jewellery because there weren’t that many people that looked or dressed like me. Also, people in the West, and also back in Kathmandu, were critical of my body because of how scoliosis affected my back,” says Dolma, who had to face discrimination because of how she looked, physically and racially.

While it took some time for her to accept herself and adapt with all the changes that were happening in her life, with time she started embracing her Dolpo culture as well as the American culture, which she credits various forms of arts for helping her.

However, very few books were written about her homeland Dolpo, that too written by a Dolpo native. The ones that have been written often have a romanticised view of the place, forgoing the everyday struggles of the native people. And that’s why she decided to write a memoir, 15 years back, so she could write and share with the modern world the unique cultural heritage as well as the struggles of the Dolpo people, who are isolated from the rest of the world, she says.

For writers, spending 15 years on a single book—comprising only 300 pages—could be taking too much time. Dolma says it took her time because adjusting to English, a language vastly different from her mother tongue, was difficult, as she only got a chance to learn it after she came to the US, when she was already over 10 years old.

Likewise, her academics and work also kept her busy. But regardless of her busy schedule, she always took time out and never gave up writing, which itself was emotionally consuming. “As the oldest of eleven siblings, I stayed strong for my family and myself and hardly cried, but I did cry more when I was writing because I was trying to tell the little child in me that it's okay to cry, or feel angry, scared or sad,” says Dolma.

Regardless of her struggles in writing as well as her personal life, writing the memoir was one of the most therapeutic things she has done in her life, she says, as it not only helped her to share her personal story, which is being used as an educational resource, but it also brought her close to Dolpo culture and Nepal in general, she says.

Released in January 2018, her book was well received by the people, leading her to travel in Europe, Canada, Nepal and in different states of America, where she was invited to speak about her book.

But Dolma’s creative endeavours aren’t limited to writing only. A graduate of Fine Arts from the University of Colorado, she also finds solace in art. “Art for me is not about being perfect or controlled. It is about experience, exploration, and liberty. When I make art, it empowers me and helps me cope with the overwhelming amount of suffering in the world,” says Dolma, who creates mix-media artworks, as well as sketches, paintings, and jewellery as well.

In her artworks, she constantly incorporates motifs of Dolpo culture, be it adding a fragment of a handwoven Dolpo blanket or traditional jewellery or using nature as the underlying theme. Likewise, she also frequently uses stones in her mix-media artworks and creates necklaces as well. According to Dolma, this is because of her close association with nature, she says.

While Dolma may now have spent more years in America, almost 25 years, her connection with her homeland is still embedded deeply in her mind. To stay connected with her native land and to contribute to the welfare of the people of her homeland, she contributes a certain portion of her sales for educational and medical support regularly.

And while, over the years, Dolpo has been gaining attention from both local and foreign visitors, who are mostly visiting the place to witness the breathtaking turquoise coloured lake Phoksundo, the culture of Dolpo people, their needs and struggle are hardly covered by the mainstream media, with much focus being only tourism-driven.

And this is why Dolma believes more and more people from Dolpo should be encouraged to write their own stories so there’s an alternative space for the local point of view to flourish.

“People often write about the breathtaking landscape of Dolpo, which is very beautiful for sure, but it’s important to write about the challenges of traveling, harsh weather conditions, and the day-to-day life of the people who live there which requires lots of listening and respect for the people’s culture and religion,” she says.

As an artist and writer, while Dolma plays with her imagination and doesn’t want to limit herself, for her cultural identity and her memories of her childhood, in Dolpo, always serves an inspiration in her artworks, and serves a medium of expression and self-reflection

“I get goosebumps sometimes knowing I can read and write now, to voice my thoughts and ideas. Twenty-five years ago, forget about getting education, I didn’t know if I would live to be 11,” she says.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)