Culture & Lifestyle

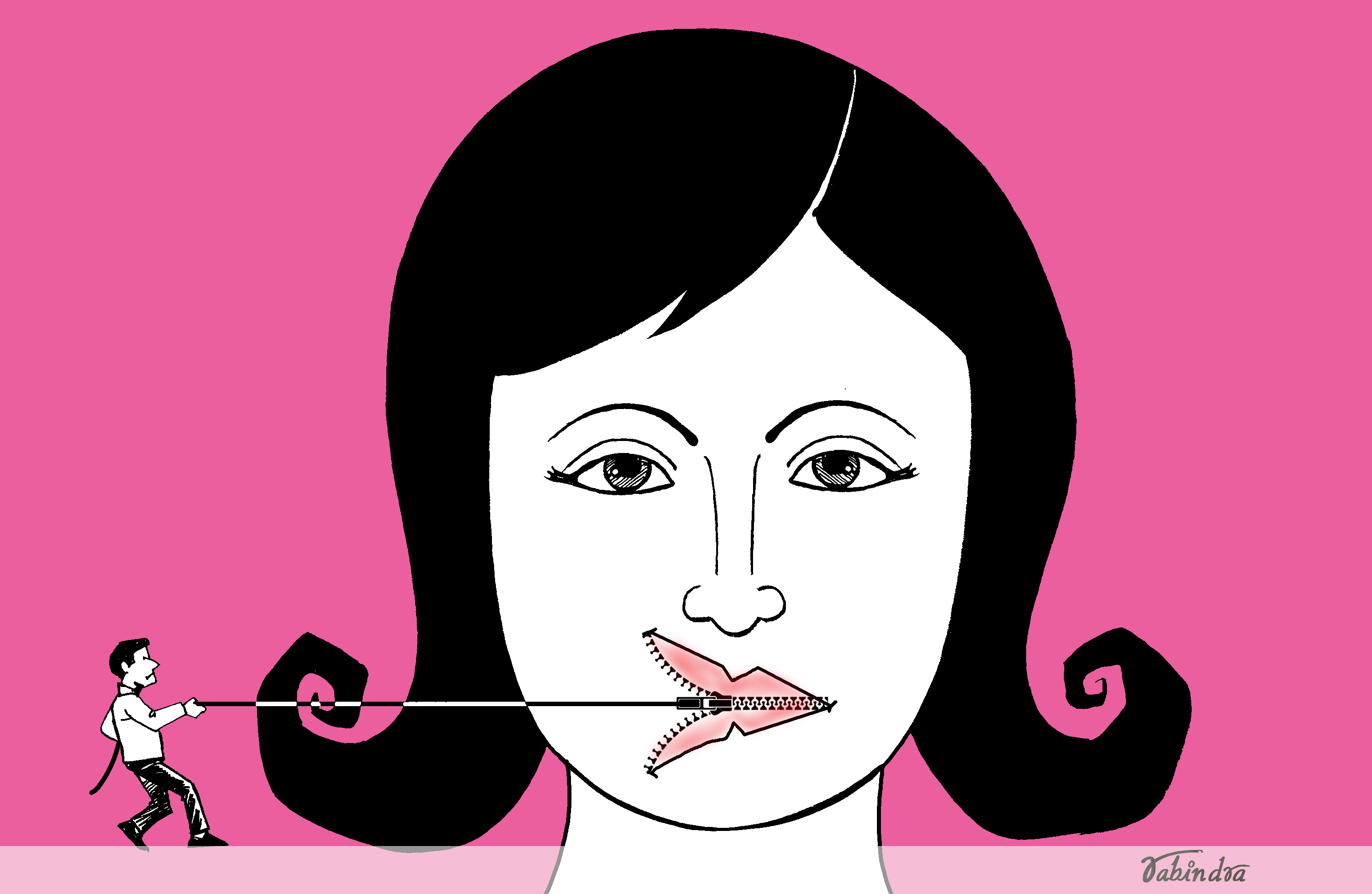

Less than a year later, Nepal’s men of #MeToo are back to work

When women came forward to share stories of sexual harassment, there was hope that powerful men were finally going to be held accountable. But today, it’s business as usual.

Bhrikuti Rai

Earlier this year, when reports about sexual harassment in the Kathmandu theatre community became public, there was a flicker of hope that Nepal’s MeToo movement was finally taking off. Unlike MeToo stories from Nepali academia or politics, which had led to more counter-accusations than introspection, Nepal’s theatre fraternity publicly came out with statements condemning sexual harassment, and said they were in solidarity with the women who decided to speak out.

Even the men who were accused of harassment—Raj Kumar Pudasaini of One World Theatre and Rajan Khatiwada of Mandala—apologised and released remorseful statements. But Sunil Pokharel, the venerable founder of the now-defunct Gurukul Theatre, remained silent, despite also being accused of impropriety. Mandala and One World Theatre went a step ahead and suspended Pudasaini and Khatiwada from several of its projects for a year.

It was a rare instance of men being publicly held accountable by their own institutions. But just a few months later, Khatiwada and Pokharel had already found a stage and an audience at Mandala. According to at least half a dozen people who saw Khatiwada’s apology post on Facebook in April, the post is no longer available. Allies of the MeToo movement, who had initially cheered on the efforts made by the theatre fraternity to address sexual harassment, are now calling out double standards, saying the space being given to the accused is a huge blow to whatever little the movement had gained in the past year.

“These men continue to get space, if not here then there,” said writer Anbika Giri, who was one of the few people to call out Mandala Theatre for casting Rajan Khatiwada in its most recent production Mahabhoj. “It is infuriating and also disappointing to see how institutions are complicit in enabling these men to get away with their abuse of power, without stern repercussions.”

Allowing powerful men make a comeback without any repercussions or without losing their social capital has implications for women who come forward with their stories, and also those who might want to tell their stories in the future.

[Read: Fed up by harassment, women are going online to share their stories]

“I cannot imagine how some of the women who said they were harassed by Khatiwada must have felt when they saw him on stage,” said Giri. “It’s easy to get disheartened because it does seem like nothing happens when you speak and you only become a source of gossip among your peers.”

But Mandala has defended its decision to cast Khatiwada in the play. The theatre company’s director Srijana Subba, who in April had released a statement expressing solidarity with the MeToo movement and vowing to investigate allegations of sexual harassment against Khatiwada, said Mandala did what they could by accepting his resignation as general secretary of the company for a year.

“We let him go from his official position at Mandala and he hasn’t been involved in anything, but we cannot keep an eye on what people do outside of work,” said Subba. “Does the MeToo movement have a rule that says perpetrators need to be boycotted from everywhere?”

Subba further said that the women who had accused Khatiwada of sexual harassment didn’t come forward publicly, making it difficult for them to take further action.

Speaking to the Post in May, Somnath Khanal, another actor with Mandala, had said the theatre company would formulate guidelines to make it clear that it would not tolerate harassment. Nearly five months later, Mandala still doesn’t have much to show, although it has said it will put together a gender and diversity workshop in the coming weeks.

“We are working towards formulating a mechanism in Mandala to ensure that victims know where to go to take action,” Srijana said, without getting into the details.

Subba, who is also one of the actors in Mahabhoj, said that sharing the stage with Khatiwada post the allegations and his apology didn’t feel any different.

“We’ve always worked together and this was no different,” she said tersely. “We needed an artist, he was there and we approached him.”

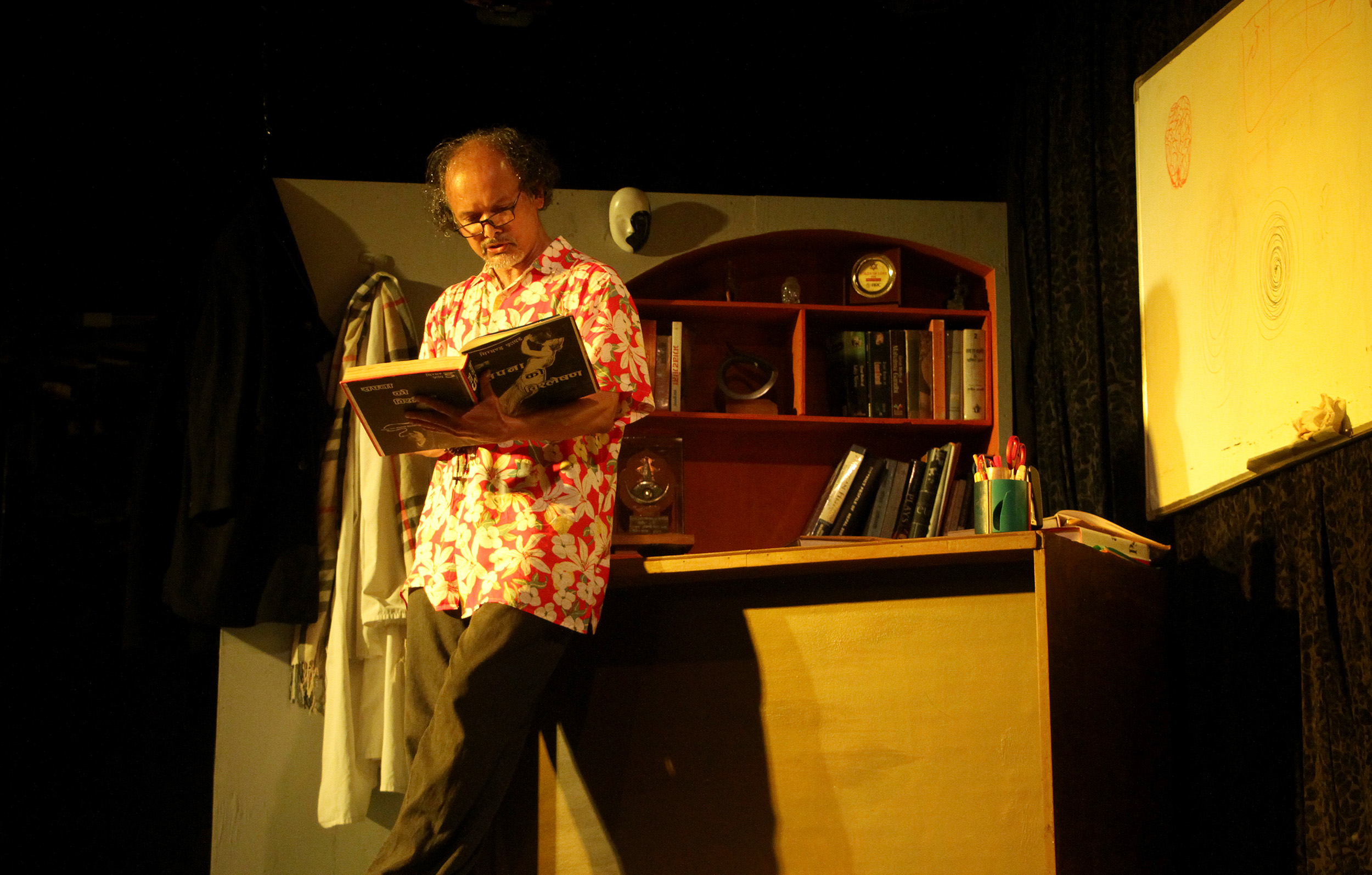

Subba isn’t the only one in the theatre community to not shy away from working with alleged perpetrators of sexual harassment. Raj Kumar Pudasaini and Sunil Pokharel, who, according to a report in Shukrabar weekly, showed up drunk for rehearsals and touched women inappropriately, recently starred in a play called Mimansha. The play was also shown at Mandala.

Mimansha’s director Prabin Khatiwada defended his decision to cast Pokharel as the lead actor in the play, saying that while he thinks it’s important to keep the conversation about sexual harassment in the workplace alive, it’s not his responsibility to judge or hold people accountable “based on rumours.” He said that news reports about sexual harassment allegations against Pokharel didn’t cross his mind at all when he was working on the play.

“I am just a theatre person who wants to work with good actors, and that’s what I did by casting Sunil Pokharel in my play,” said Prabin, who was also Pokharel’s student at Gurukul several years ago.

Unlike some of the criticism towards Mandala for casting Khatiwada in Mahabhoj, Prabin’s play Mimansha escaped scrutiny. And this lack of questioning is what Prabin frankly says is the reason he doesn’t regret casting Pokharel in his play, and would happily continue working with “good actors” like him.

“All I can do is do my job sincerely,” he said. “Nobody questioned me, if they had maybe I would’ve thought about it.”

Questions about redemption after MeToo—should they? can they?—have been a conversation not just in Nepal, but around the world where powerful men have attempted to make a comeback. In the US, where the MeToo movement kicked off two years ago with explosive investigative reporting that led to the downfall of several powerful men, like Hollywood heavyweight Harvey Weinstein, have faced legal consequences. But others, like comedian Louis CK and American journalist Charlie Rose, who also faced multiple accusations of sexual harassment, are already plotting their return.

Next door in India, well-known actor Nana Patekar and filmmaker Vikas Bahl, who were accused of sexual harassment, have already returned to work. The MeToo movement in India hasn’t just been marked by a lack of accountability from institutions, but also by the strong pushback from the accused men. Former minister of state for external affairs, MJ Akbar, who was accused of sexual misconduct by journalist Priya Ramani, stepped down from office last year to pursue a defamation case against her.

A lack of sincerity

Subba, in her defense of Khatiwada’s comeback, said that apologising and moving on should be the way forward for perpetrators of sexual harassment.

“If an artist apologises for their behaviour and wants to work, I don’t think we need to boycott them from all public spaces,” said Subba.

But vocal champions of the MeToo movement say it is the very nature of Nepal’s limited public space—comprising of a handful of influential men—which has pushed back on MeToo stories and the ripples it could create in shifting attitudes towards sexual harassment in the workplace.

Writers like Sabitri Gautam, who has been one of the most critical voices in pushing forward conversations around Nepal’s MeToo movement, feel that people with influence don’t want to poke the issue because they fear reprisals from powerful men.

“These people who endorse the work of perpetrators on social media and in real life are implying that they aren’t supportive of the MeToo movement,” said Gautam, referring to the praise heaped by the who’s who of Nepal’s literary and intellectual circles on the Mahabhoj play. “These endorsements weaken the overall movement.”

And the media has been just as complicit, she says, continuing to give prominent space to men who have been accused of sexual harassment.

“For the media, these stories of sexual harassment are just occasional scoops, because the kind of space they give these men is symptomatic of how the media continues to perpetuate structures, which then give leeway to such behaviour,” said Gautam.

While a handful of social media users have called out organisations like Mandala and a section of the Nepali press on their silence and inaction in addressing harassment, for others, not much has changed. Gautam points towards recent examples of how men—like former Tribhuvan University lecturer Krishna Bhattachan and former Kathmandu mayor Keshav Sthapit, who were accused of sexual harassment but dismissed the allegations, continue to be invited and honoured in public forums.

The allegations against Bhattachan, an influential academic and indigenous rights activist, ranged from him making lewd remarks to inappropriately touching students during advisory sessions at his residence. After the Post reported on these incidents last January, Bhattachan accused the women of trying to attack the indigenous people’s movement with “baseless allegations”. After keeping a low profile on social media when the allegations began surfacing late last year, Bhattachan’s social calendar has remained full in recent months. Just last week, he spoke about indigenous rights at an event in Kathmandu, sharing the stage with some of Nepal’s most progressive writers and thinkers.

“The fact that these organisations working for marginalised groups invite Bhattachan speaks volumes about how these perpetrators’ actions are swept under the rug by powerful individuals and groups,” said Gautam. “How do we get to take this movement forward when there is a dearth of sincerity?”

People from within and outside the theatre community who have witnessed the MeToo movement spark a debate—only to see it fizzle without any concrete action—say pressuring corporations and donor agencies that extend support to theatre groups like Mandala could lead to some accountability. The play Mahabhoj, currently being shown at Mandala, has a number of sponsors and supporters, with GIZ, the German development agency, leading the pack.

GIZ, which has supported many arts and culture initiatives in Nepal, including extending different kinds of support to Mandala Theatre, adopted a zero-tolerance policy on sexual harassment in the workplace back in 2013. In an email reply to the Post, GIZ said that it ensures its zero-tolerance-policy on sexual harassment also applies to the activities and partners it supports, and a non-fulfilment leads to the termination of the contract. However, it refrained from commenting on Mandala’s decision to give space to the accused Khatiwada and Pokharel in plays the company has produced and showcased, citing their contract’s timeline.

“The cases Mr. Khatiwada was accused of and which were covered by the media happened years before GIZ-CPS partnered with Mandala Theatre and they were revealed after the partnership had started,” Elke Foerster, country director of GIZ Nepal told the Post. “Mandala Theatre dealt with the case in transparent ways and in close and sensitive dialogue with the affected person.”

But some in the theatre community say this issue has been anything but transparent. Earlier this month, Akanchha Karki of Kausi Theatre shared a message on Twitter about the bullying and threats some theatre actors are facing for raising the issue of sexual harassment.

“We’ve been asked to stay quiet for a few days because there is a conspiracy to exclude anyone in the theatre community who speaks up about #MeToo,” she wrote. “Where are the responsible seniors in our fraternity at a time MeToo has been politicized to such an extent?”

Others say GIZ as donors need to do more to ensure the projects and organisations they choose to work with adhere to the same policies when it comes to sexual harassment.

“If organisations supporting places like Mandala have zero tolerance for sexual harassment, they better find ways to implement it,” said Manushi Yami Bhattarai, a leader of the Samajbadi Party, Nepal. “They can’t get away with double standards.”

Light at the end of a long tunnel?

Less than a month into his new job as coordinator of Annapurna Post’s Saturday supplement, Bimal Acharya decided to do something unusual last March. Instead of focusing on major events in politics and entertainment reported in the media for the Nepali New Year special, he did something unusual by Nepali newspapers’ standards—he dedicated the entire supplement to MeToo stories.

“Stories about sexual harassment were making noise, if not on mainstream media, then on social media and beyond for sure,” said Acharya. “For me, this was the biggest story of the year.”

There weren’t any reported stories in the supplement, just personal narratives from women who spoke about the countless times they had been touched, groped, and felt humiliated and helpless. Since then, Acharya has received countless stories about similar episodes, which he says have been pushing forward conversations about sexual harassment in public and private spaces.

“Maybe it’s reading these stories and experiences of other women which has encouraged others to talk about their own,” he said.

And among readers who found the courage to share their own stories of experiencing harassment was writer Shivani Singh Tharu. Before the MeToo movement kicked off, and personal accounts of harassment gained space in Nepali newspapers, Tharu thought her story wouldn’t be relatable to others because of the shame she had been conditioned to associate it with. So she was pleasantly surprised by the response her widely-read personal essay, 34 inch D, received. In the piece, Tharu writes about her relationship with her body, shaped by the harassment she endured as a young woman in different stages of her life.

“Even men reached out to me for sharing this story, which was something I hadn’t anticipated,” said Tharu. “But these stories need to go beyond helplessness, and hopefully in the future, we will hear stories of women who fought and won these battles of sexual harassment.”

But Tharu says that isn’t possible unless the media changes the way it writes about woefully underreported stories of sexual harassment. She says the media, and the male readership, need to stop treating these stories as sensational pieces.

“Since these stories are about taboo subjects like sex, people’s reading of these stories might contain an element of voyeurism, which will not take the conversation forward,” said Tharu.

Acharya says he is aware of how Nepali newsrooms have shied away from investing time and resources to report these stories. But he admits it might just be a matter of self-preservation.

“Maybe there is a sense of fear in our media and our newsrooms that if we start writing about harassment, similar stories might come back to bite us as well,” he said. “There are skeletons in our closet, too.”

After Annapurna Post published stories of women speaking about being harassed, Acharya says many of his male colleagues and friends have mocked him for “only publishing women’s stories,” but he says such remarks don’t bother him.

“For years, we didn’t have that space or the vocabulary to talk about these violations to our body and dignity, but now we finally do,” said Bhattarai, who has been talking about the need for structural reforms to address sexual harassment head on. “It’s time we make strategic use of this momentum to make tangible gains.”

Some progress is slowly being made.

More than six months after a programme was first held at Tribhuwan University to start the conversation about sexual harassment in the wake of reports about continued harassment in its sociology department, the university finally formed a committee to set up a mechanism to deal with these concerns earlier this month.

“While we wait for structural changes to address sexual harassment at the workplace, we need to do whatever we can on a personal level,” said Gautam, the writer. “We need unity among the few allies we now have.”

9.83°C Kathmandu

9.83°C Kathmandu

.jpg)