Culture & Lifestyle

No country for bookworms

The lack of public reading spaces and well-maintained libraries is hindering the reading culture among Kathmandu’s new generation of book lovers..jpg&w=900&height=601)

Arya Mainali & Diya Rijal

At his primary school in Thailand, Riyush Ghimire remembers being encouraged to read books—a habit that stuck with him when he moved to Nepal.

Once in Kathmandu, to feed his reading appetite, he borrowed books from his school library. Then his search for more variety lead him to the AWON library in Kupondole. But it’s been around two years since he stopped going to public libraries altogether.

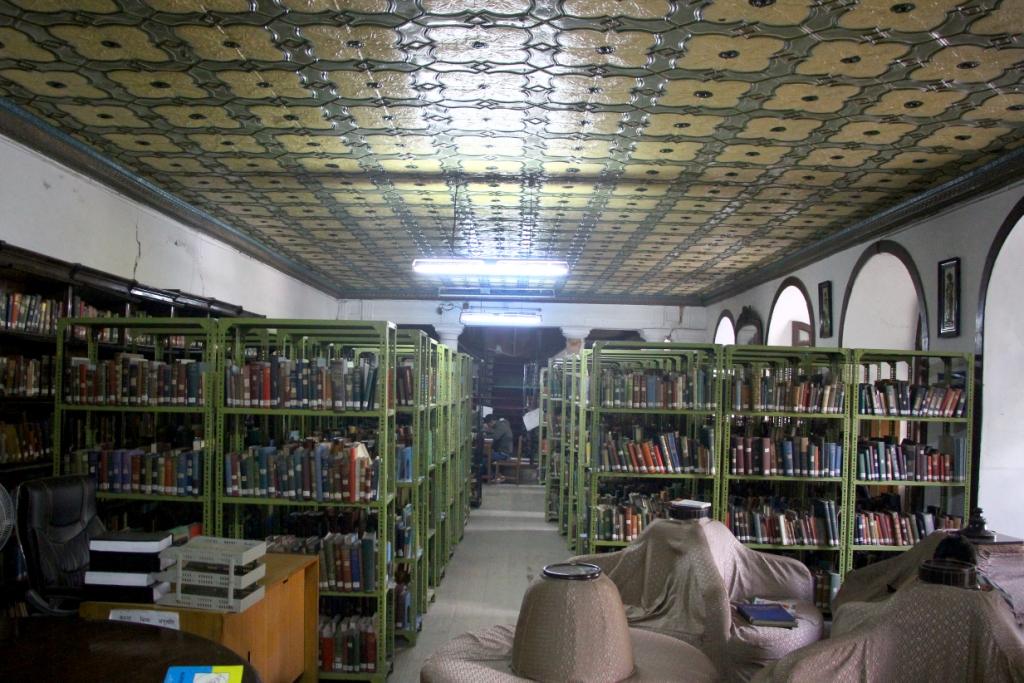

Ghimire stopped going because they did not have clean and comfortable reading spaces, nor enough books. And although in recent years e-books have become a book lover’s best friend, there are people like Ghimire, who prefer reading physical books. But the libraries in the Valley are not resourceful or well-maintained.

AWON library, run by Active Women of Nepal, was one of the most popular public reading spaces among the residents of the Kathmandu Valley. Before the 2015 earthquake, the AWON library operated on a two-storey building in Kupondole with about 10,000 members. The library now runs as Rotary AWON Library in the Rotary provided space in Thapathali. According to its online database, Rotary AWON now has 537 active members—a massive drop from the 10,000 members it once had.

“Compared to the space in Kupondole, AWON in Thapathali wasn’t aesthetically pleasing. The new space did not support a reading environment,” Ghimire says.

Since many libraries do not stock newly released books, readers are forced to choose from the old books that have been sitting in the library shelves for decades. “I visited libraries in Jhamsikhel, Thapathali, and Patan, and they are all in a bad state,” says Rea Mishra, another 19-year-old. “The limited books that are available are covered in dust, and the environment is not reader-friendly at all.”

According to Mishra, she has never borrowed a book from public libraries in Kathmandu. Having spent her childhood in London, she says she was never out of books to read and when she later moved to Nepal 10 years ago, her school library provided her with the same privilege. But after graduating from her high school, she had to look for alternatives. So, she visited libraries in the Valley but found them lacking, even the ones operating for decades and receiving funding directly from the government.

The lack of public reading spaces specifically hit her when she started preparing for her SATs. “My friends and I used to go to cafes in order to study as a group,” Mishra says. “Had public libraries been kept in a better state, we would have gone there to study.”

Besides being a place of learning, public reading spaces, especially for young book aficionados, can be a place of sanctuary, says Professor Dr Kedar Bhakta Mathema, former Vice-Chancellor of Tribhuvan University.

“The school education system is still very much ‘exam-oriented’ that focuses more on facts than opinions,” he says. “The schools usually forces students to limit their thoughts and knowledge to what they learn inside the classroom, which diminishes already scare reading culture.”

Many schools in Kathmandu may have allocated space for libraries and have assigned ‘library periods’. But these assigned reading hours that are supposed to help students learn outside of their classroom usually ends up being extra-time for students to stay out of the rigid classroom system.

“We did have library period once a week in school. But most of it was spent gossiping with friends,” Ghimire says. “It was ‘uncool’ to go to the school library to borrow books.”

Ghimire says his school schedule was always filled with classes. Visiting the library once a week was like an escape—40 minutes away from academic books meant 40 minutes to have fun with friends. For Ghimire, the school library was not the space he wanted to be in. Although the library was filled with books, they never catered to his interest.

“I started going to AWON because the library in my school was not very flexible with the kinds of books we wanted to read,” Ghimire says. “If they says we had to read Nepali literature from a certain section, we had no choice but to do it.”

But some schools have taken steps to change such rigid structure says Heeramaya Tamang, co-ordinator at DPS School, Kuleshwor. She herself initiated such a step, by organising a trip to Ekta Books for primary school children to buy books for the school library. Although DPS School has a library, the books there are limited.

“I thought of bringing the students to pick up books for the library because they will have the liberty to choose the books that they would like to read,” Tamang says. She wishes for her students to visit the library more often to develop a reading culture.

Tamang herself has never been to a public library in Kathmandu, however. She prefers the bookstore because the books are organised, easy to find and the atmosphere is pleasing. But she would rather take her students to a well-maintained library than a bookstore to read books.

But going to a bookstore is not the same as borrowing books from libraries. Apart from providing a favourable reading environment and diversity of reading materials, libraries are an inexpensive means to access books.

.jpg)

To help fellow readers pick better books, Aashruti KC, 24, posts reviews of the books she has read on her Instagram page. She had initially created the page as a platform to discuss books, but later moved to reviewing books instead. In the two years of reviewing books, KC has gained over 1,300 followers who wait for her reviews to decide which book to read next. However, not everyone can afford to buy expensive new books to support their passion for reading.

“Most of my young followers often tell me that buying books are expensive,” says KC. “If libraries here were maintained, it would help young readers access books, which inturn would encourage a reading culture."

Furthermore, the government's decision to impose customs duty on imported books has become a bigger financial burden for students and readers alike. “It is absurd that there is a tax on foreign books, which will only further be a disincentive for people to read books,” says Professor Mathema.

Not only will the tax be a burden on book buyers, it will also be an obstacle for libraries to invest in recent publications. And, since libraries depend on donations to update their stocks, new books often do not make it to the shelves.

The public libraries of Kathmandu that run under the government are in even worse shape. After the 2015 earthquake, the Nepal National Library building at Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk, suffered massive damage. As a result, the building was forced to shut down. The books were shifted into a storage space, and the library was reopened with selective books available to the public.

As plans to rebuild the library undertake, the Chief Librarian, Upendra Prasad Mainali, says the main focus of the new library will be to promote the reading culture.

“A library is not supposed to be racks and racks of books only,” Mainali says. “We want the new library to have facilities like a cafe or cafeteria, washrooms, music room or dance studio that will encourage people to spend more time here.”

For now, the national library is working on digitising their old books. But some book lovers have taken upon themselves to foster the culture of building public reading spaces.

Jagannath Lamichanne and his wife Bidushi Dhungel, opened Bodhi Books and Bakes, a small cafe, four years ago to provide a quiet, yet lively space for people who would like to do their work without being disturbed. The walls of Bodhi has bookshelves filled with books from Lamichhane’s personal collection. Customers have the option to bring their own books or read the books there.

Lamichanne believes the reading culture in Kathmandu needs a new direction for youths to invest more time reading books other than those required for class. Bodhi welcomes customers to a creative space where they have the freedom to read or work.

“Most people who visit Bodhi ask for the WiFi password as soon as they sit down,” Lamichhane says. “We need to utilise technology and alternative media to get the youth excited about books.”

Lamichhane believes using media in public reading spaces is a very important in the digital era. As the world shifts from traditional print to digital media, reading spaces like any other should utilise alternative media to keep readers entertained.

The new generation book lovers agree with Lamichhane. “People aren’t going to visit libraries if they keep operating as it is now. Authorities have to create a new aesthetic and a new environment,” says Mishra. “If libraries work to achieve this, more people will definitely visit libraries.”

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

22.37°C Kathmandu

22.37°C Kathmandu