Opinion

Library blues

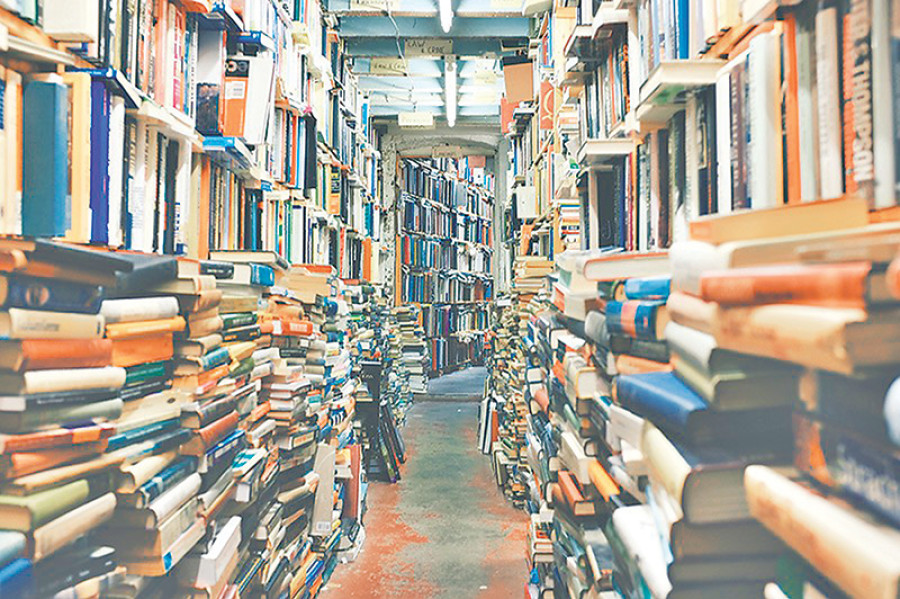

Public libraries are a treasure. We must learn to see them for what they are

I received an invitation from a young scholar named Rishi Raj Adhikari to speak on the theme ‘Why is the book journey needed?’ in Kathmandu on February 8, 2019. I had met Rishi and his friends in Delhi when I was attending a colloquium at the South Asian University in May 2017. Interestingly, these university students had approached me to discuss diverse subjects, from literature to philosophy . A government minister, police chief, a dynamic publisher, a novelist, and a woman film actor were Rishi’s other invitees. Triggered by that, I am briefly discussing here the historicity of libraries in Nepal.

From palaces to libraries

I have spoken about libraries and written articles and delivered seminars on the relationship between readers, space, and books on a number of occasions. But the reality has changed. Speaking or writing about libraries at Nepal Mandala after the April 2015 earthquake the subject of library has catapulted into memory lane with a jolt, as it were. There remain only blues to narrate about books and spaces here. The greatest irony about books in Nepal is that collecting books remained a passion either of individuals associated with the aristocracy, or of those people who could afford to buy books to keep in good numbers. That they were also scholars holds special significance.

One such person who combined passion with scholarship was the late Hrishikesh Shaha. He was also a writer. What struck me every time I visited him was the sight of the skin of a big tiger put aslant his huge book racks. That minuscule melange of aristocracy and scholarship explains my theory here. Shahaji—I addressed him by that name—moved me to tears one day at Mandala Book Point where he wanted to buy a book, but for some reason he did not have money. He was not well at that time, which I knew because I had visited him a couple days earlier. It became evident afterwards, that very book had pulled him out of his bed. He offered Madhablal Maharjan a gold coin or asarfi for that book, which Madhab declined saying pay me when you have money, otherwise I give this book to you, sir”. I cried when I saw Shahaji’s eyes steaming owing to the bookseller’s gesture. Such was the passion of the person who had a huge library at home. Most possibly, that was Shahaji’s last outing. He passed away a few days later.

How personal libraries arose up and how much was the collectors’ passion responsible for this phenomenon is difficult to assess. But huge collections of individuals were responsible for creating big libraries in the metropolis. I would like to allude to a few of them here.

Kaiser Shumsher Rana had a great collection of books, which he housed in his palatial building known today as Kaiser r Mahal. As a library, it gained shape after Kaisar’s wife ‘Her Highness Krishna Chandra Devi Rana’, to cite the appellation, donated 50,000 books, documents and pictures to the Nepal government in 1969. The same Mahal space was used for the library. This library had impressed both Nepali and foreign scholars. Nehru too had visited the library earlier, and admired it. I got to know this library very well when my friend Saket Bihari Thakur of Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS) was cataloguing the stocks of this library for the first time in 1973. A lithographed catalogue was brought out. Thakur’s catalogue covers books about Nepal studies. Two years after that, Thakur catalogued similar possession of the Rastriya Pustakalaya of Harihar Bhawan.

Both libraries are in a dismal state post the Gorkha earthquake 2015. But it has been four years since the disaster struckand yet no significant efforts have appeared to have been made to restore the space and properly catalogue the books. A report produced by Ganesh Rai of Kantipur on October 7, 2017 says, the Rastriya Pustakalaya’s possession of 15,000 books and magazines packed in sacks and hauled up in stacks, are kept in different places. He found them open to hazards when he visited them in Mahendra Bhawan of Gyaneshwor, where they are stockpiled. This library, instituted by the government of Nepal by buying initially the huge personal collection of Guru Hemraj Pandey of the court, in 1956, and housed in the spacious palatial building called Harihar Bhawan, was considered Nepal’s major library.

The Central Library located in Kirtipur university premises, which remained a centre of study for students and teachers of Tribhuvan University alike, has a similar story too. This library too was badly hit by the earthquake. Books which have tumbled out of the racksas the structures collapsed, are not yet properly placed back in their respective spaces.

A report says, the Nepal National Education Commission, appointed in 1954, recommended the establishment of a strong central library to serve as the centre for study and research and greatly enhance knowledge. Accordingly, an agreement was reached between the Government of Nepal and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) on April 30, 1957 to establish a Central Library in Kathmandu. It was housed at the erstwhile Rana palace called Lal Durbar under the guidance of Dr E.W. Erickson. After the Tribhuvan University Act was passed in July 1959, the university central library came into existence. It was later moved to Kirtipur.

The narrative of personal initiative does not end there. Madan Pustakalyaya, created and managed by Kamal Mani Dixit, is another example of a personal collection. Similarly, Dilli Raman Regmi’s centre was his personal dream, a space of covenant, but unlike the latter example, it was a scholar’s working desk which employed a book rack system.

Apathy towards books

To make some intervention from the public sector to start a public library, Tirtharaj Wanta, Narayan Khadka and a few others—I was also a member—formed Society of Kathmandu Valley Public Library in 2003. Now, inundated by huge number of books all around, a few staffs can be seen managing the library in a narrow space in Bhirkuti Mandap. But this collection could be turned into the most needed public library with proper space, management, and finance. But the same is not likely to happen anytime soon considering the the modern state of Nepal’s ongoing apathy towards books.

22.11°C Kathmandu

22.11°C Kathmandu