Culture & Lifestyle

Sujan Chapagain dreams of a grand concert someday

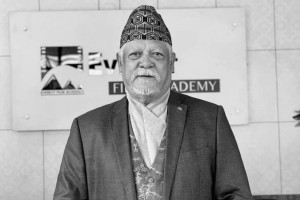

The ‘Teenpatey’ singer speaks of how folk roots, long training, and unexpected virality shaped his career.

Sanskriti Pokharel

During the Covid-19 lockdown, Sujan Chapagain’s debut song, ‘Teenpatey’, was first shared on TikTok. It slowly became popular, and many regarded it as a form of therapy. This led Chapagain to understand that music is more than just awards and applause; it can also heal and bring people together.

Chapagain’s story starts modestly, which adds to its appeal. His first public singing was at his school mass in fifth grade, where he performed Udit Narayan’s ‘Malai Yo Jindagile Chot Diyo’. The heartfelt performance moved many, even making some cry, and he won first prize, confirming early on that his voice mattered.

Despite the applause, Chapagain’s path to music was not straightforward. He completed his +2 in science in Chitwan, where family and friends nudged him towards agriculture. Chitwan is home to the Agriculture and Forestry University and remains a vibrant hub for these fields. Initially, he did not consider music a career; instead, he viewed it as a passion and craft to pursue alongside a traditional profession. When Nepal Idol’s first season aired, and he was selected in the early rounds, he chose not to participate. The audition was in Kathmandu, and with exams nearing, he decided to focus on his studies. Looking back, he says he has no regrets. “If I had continued, I might have gained fame faster and received more invitations, but taking a break allowed me to deepen my musical skills instead of seeking quick fame,” Chapagain explains.

That practice was deliberate and demanding. Chapagain studied under several gurus over five years, learning the basics of classical singing in Chitwan for two years before moving to Kathmandu to pursue eastern classical training for another three years. He absorbed the technical rigour of semi-classical traditions and cultivated a voice to carry the ornamentation and discipline those styles demand. His songs are technically complex, requiring long hours of rehearsal to shape phrasing, tone and breath. ‘Ghumi Ghumi’, a folk piece, pushed him to develop a folk tone he did not yet possess.

He explains that immersing oneself in the emotional essence of a song can be beneficial. Sometimes, performing a heartbreak song makes him feel sad. For a singer, acting and genuine expression often merge.

The breakthrough didn’t come from a reality show but from a pandemic. ‘Teenpatey’, his first song, premiered in 2020 as the world went into lockdown. Originally uploaded to YouTube, it gained new popularity on TikTok, where users incorporated snippets into their daily videos as background music. The song’s fresh sound and unique style resonated quickly and broadly. “People were stressed during Covid-19. They needed therapy, and music became therapy for them,” he said. What started as a modest release unexpectedly opened the door to a larger audience. TikTok’s viral loops transformed a local singer into a recognisable name.

The new visibility influenced his decisions significantly. Becoming independent gave Chapagain artistic liberty, enabling him to compose and arrange music without conforming to industry standards. However, this freedom also brings operational and promotional hurdles that a label typically manages. He openly discusses the trade-offs involved. While independence fosters creative risks, it also requires learning about marketing, collaborations, and logistics. His strategy strikes a balance: he aims to continue creating independently while also entering the film music scene to reach broader audiences.

Chapagain credits Chitwan for much of his musical identity. He says, “I grew up surrounded by Gandharva traditions, rivers and jungle edges, small towns where local sound and rhythm are woven into people’s daily lives. I feel nature’s energy in my work, and it has become a source of inspiration.” His music’s textures reflect that attachment to Chitwan.

Live performing has been a relatively recent chapter. Chapagain admits he has not done many shows yet. He first wants to increase the quantity of his songs, and further strengthen his band. His first international experience was an Australian tour with his band at the time, Sujan Chapagain and The Infinity, where they played in seven cities. Before that, there were performances in Kathmandu, Pokhara, and Chitwan. Fans sometimes react with an intensity that surprises him. On one occasion, a fan threw a phone onto the stage, eager to get a selfie, and the phone hit his body. The incident is now told with laughter, but it highlights the ardour his songs inspire.

Some of the responses have been quieter and more profound. A fan who had been paralysed for several years told him that his music aided the recovery process. He observes that men have become a significant part of his audience despite popular belief that men are less emotionally expressive. Messages arrive saying his emotional songs make listeners feel romantic or help them through difficult nights.

The song ‘Eklai Bhayeni’ became emotionally linked to a couple’s story. Srijana Subedi and Bibek Pangeni were among the listeners. After the song was released, Bibek, who was critically ill, passed away a few days later. Fans now associate that song with the couple. For Chapagain, this shows how music can develop its own life and hold meaning well beyond what was initially intended.

Creative collaborations have become a consistent element of his work. The band Sujan Chapagain and The Infinity, officially formed in June 2022, have performed across Nepal and abroad. Their music seeks to blend traditional Nepali folk elements with contemporary sounds, maintaining the authenticity of folk instruments while making them resonate with modern audiences. Hark Saud, the band’s lyricist, provides the lyrics that underpin Chapagain’s melodies, and Nabin Chauhan enhances their sound with evocative visual storytelling. Together, they strive to craft music that feels generational.

Beyond singing, Chapagain is broadening his musical skills. He is learning tabla and often travels during his free time. He says travel energises his imagination and keeps his life balanced; dedicating all hours to a career can sap the joy from creation. For now, travel, tabla practice, and composition make up the other half of his daily routine.

Chapagain also aspires to create films. His team, which produced ‘Teenpatey’, worked on ‘Oon Ko Sweater’, where he performed most of the soundtrack. Transitioning from music to film felt like a natural progression for a group eager to tell stories too vast for a music video. “Our dream was to make a musical movie,” he explains.

Chapagain dreams of a grand concert someday, but he is patient. He wants to strengthen his band and build a broader repertoire before staging a large-scale show. For Chapagain, the work is cumulative: every guru’s lesson, every competition in school, and every practice adds up to a musician who knows both craft and consequence.

“Music comforted people during the hardest days and gave me my path. I want to keep learning, make songs that touch people, and one day give a big concert with my band when we are ready,” says Chapagain.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu