National

Three of Nepal’s largest public libraries were badly damaged in the 2015 earthquake. Only one has risen from the debris.

The Kaiser Library, one of Kathmandu’s few public libraries, is part of the larger Keshar Mahal palace complex and a work of art. Built in 1907 by Chandra Shumsher for his son, Kaiser (Keshar) Shumsher, the library holds over 50,000 books—25,000 of them donated to the Nepal government by Kaiser’s wife after his death in 1965.

Alisha Sijapati

Inside the stately Kaiser Library, HS Wagle is sitting on a wooden bench, bent over a newspaper—one of just eight visitors.

Wagle, a 50-year-old sociology lecturer at VS Niketan College, first came to the library as a teenager. More than three decades later, he’s still a regular visitor, not just to read the papers but also for research and the library’s large collection of interesting books. He also admires the architecture and decor of this 112-year-old former Rana palace, adorned with old photographs and ancient artefacts.

The Kaiser Library, one of Kathmandu’s few public libraries, is part of the larger Keshar Mahal palace complex and a work of art. Built in 1907 by Chandra Shumsher for his son, Kaiser (Keshar) Shumsher, the library holds over 50,000 books—25,000 of them donated to the Nepal government by Kaiser’s wife after his death in 1965. It is a grand old building, built in the neoclassical style so popular with the Rana prime ministers.

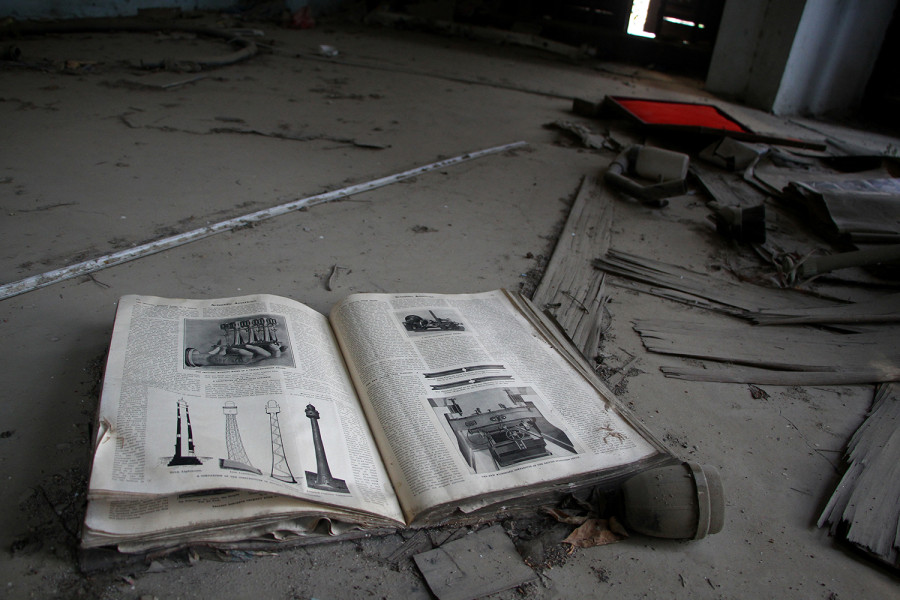

This historical landmark, however, is in a distressing state of disrepair. After the earthquakes of 2015, the building was given by a yellow sticker by the Nepal Engineers’ Association, meaning that it wasn’t damaged beyond repair but needs retrofitting if it is to stay in use. The library had to temporarily transfer its collection of 50,000 books from the building’s first floor to the ground. In the past four years, no retrofitting has been carried out.

“When I entered the Kaiser library for the first time, I was mesmerised by the exotic artefacts, handcrafted ceilings and larger-than-life portraits of the Rana family. But now that charm has died,” said a disheartened Wagle.

The Kaiser Library is not the only library that suffered in the 2015 earthquakes. Most of Kathmandu’s large public libraries suffered, and little has been done to retrofit or rebuild them.

Kaiser Library was built in 1907 by Chandra Shumsher for his son, Kaiser (Keshar) Shumsher. The library holds over 50,000 books. [All photos: Beeju Maharjan]

The Nepal National Library in Pulchowk’s Harihar Bhawan is another beautiful neoclassical building that was converted from a Rana residence into a library. This building, too, was built for one of Chandra Shumsher’s sons, Shanker Shumsher. It was converted into a library in 1961, with a donation of more than 7,000 books by Hem Raj Pandey, who served as the royal preceptor between 1904 to 1951, according to Upendra Mainali, the chief librarian.

However, Prakash A Raj, grandson of Hem Raj Pandey, said that the Pandey family had sold books to the Nepal government after the latter’s death in 1953.

The National Library, part of the Harihar Bhawan complex that houses several government offices, was given a red sticker after the earthquakes, meaning it had been damaged beyond repair and is dangerously unstable. Following this designation, the National Library, which is Nepal’s first public library, moved to a small corner of Harihar Bhawan.

“The earthquake did great damage to our library and books. Many were ruined during the rainy season,” said Upendra Prasad Mainali, chief librarian.

The Nepal National Library, which has over 150,000 books of all genres, now hosts about 12,000 children’s books in its new location. The rest of its books are now in storage at the Mahendra Bhawan School in Sano Gaucharan and the Mahendra-Ratna Campus in Tahachal. The Library plans to move into the premises of the Mahendra-Ratna Campus by mid-April but that too will be temporary.

Although Mainali is disheartened to leave the historic building behind, he is happy that the library is not only moving to a temporary space but also for the fact that the library has managed to acquire seven ropanis of land in Jamal, opposite the Rastriya Naach Ghar, for a permanent location. However, there is no telling how long it will take for the new library to be built.

“I feel pity for those books that have not got to breathe out here in the open, but something is better than nothing,” said Mainali.

The Kaiser Library too is set to move to a new prefab building within the premises of Keshar Mahal by mid-April this year, and then move back to its old building after retrofitting and renovations are complete. The plan is to complete renovations by Dashain this year, but realistically, it might take at least a year or two longer, said Dashrath Mishra, chief librarian at Kaiser Library.

“It’s unfortunate that the charm of Kaiser Library vanished after the earthquake,” said Mishra. “But recent developments have come as a relief.”

Since the earthquakes, the number of visitors have slowly dwindled. “Earlier, we had over 400 visitors signing in and out everyday, but now it has dropped by half to 200,” said Mishra.

Traditional libraries like theirs are not able to compete with the internet, social media and e-books, says Mainali, who has also seen waning numbers at the National Library.

An anomaly of a library

Patan’s Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya, however, stands in stark contrast to the state of Nepal’s two largest libraries.

Within a year of the 2015 earthquakes, the formerly three-storeyed library, established by Kamal Mani Dixit, was completely rebuilt. A beautiful modern structure—made out of rammed earth and bamboo, built by the architecture firm Abari—now houses the library’s full collection.

“Although we are a government entity, as a public trust with efficient board members, our library didn’t suffer as much as others,” said Deepak Aryal, a researcher at Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya.

Unlike the Nepal National Library and Kaiser Library, which have books in both English and Nepali, the Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya only holds books in the Nepali language—over 40,000 of them, with the oldest being a Nepali Bible printed in 1820. Along with acting as an archive and repository, the Pustakalaya also works to digitise books and pictures, in order to preserve knowledge and information should the physical copies ever be destroyed, as has happened with the National and Kaiser Libraries.

Interior of Patan’s Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya.

“The amount given to us by the government varies on a yearly basis but this year, we received about Rs 3 million which was fully invested in digitising our books,” said Aryal.

While the Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya received Rs 3 million this year, the Nepal National Library and Kaiser Library both receive roughly Rs 8-9 million every year. These funds are for everything—from new acquisitions to library maintenance and employees’ salaries.

“It takes a lot of money to maintain a library, especially now, when we are in a temporary base where it is difficult to take good care of the books and we have to digitise them,” said Mainali.

Unlike the Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya, the National and Kaiser Library both remain hopelessly behind when it comes to digitisation. Their libraries have yet to adapt to the digital age, despite their old books being in dilapidated states, with fragile bindings and infestations of silverfish, said Mishra.

“We are small government entities and maybe lowest on their list of priorities,” said Mainali. “It’s tiring to fight with the government all the time, but who else is there to support us?”

Update: This article has been updated to state clarify that according to Hem Raj Pandey's grandson, the books were sold to the National Library. An earlier version of this article said that the books were donated, based on the interview with the library's chief librarian.

13.58°C Kathmandu

13.58°C Kathmandu