Visual Stories

Inside Patan’s Golden Temple, guthiyars painstakingly restore an 898-year-old manuscript

This year, ten guthiyars took 25 days to restore the Pragyaparamita, a sacred Buddhist text, with gold ink.

Sanjog Manandhar

The essence of Kathmandu Valley’s heritage is that it is still dynamic and breathing. Unlike museums elsewhere, which are often devoid of life and turned into relics used to assume matters of the past, the temples, vihars and stupas in the Capital—despite being hundreds of years old—are still frequented by people, not just to observe, but to practice, worship and thus, keep alive.

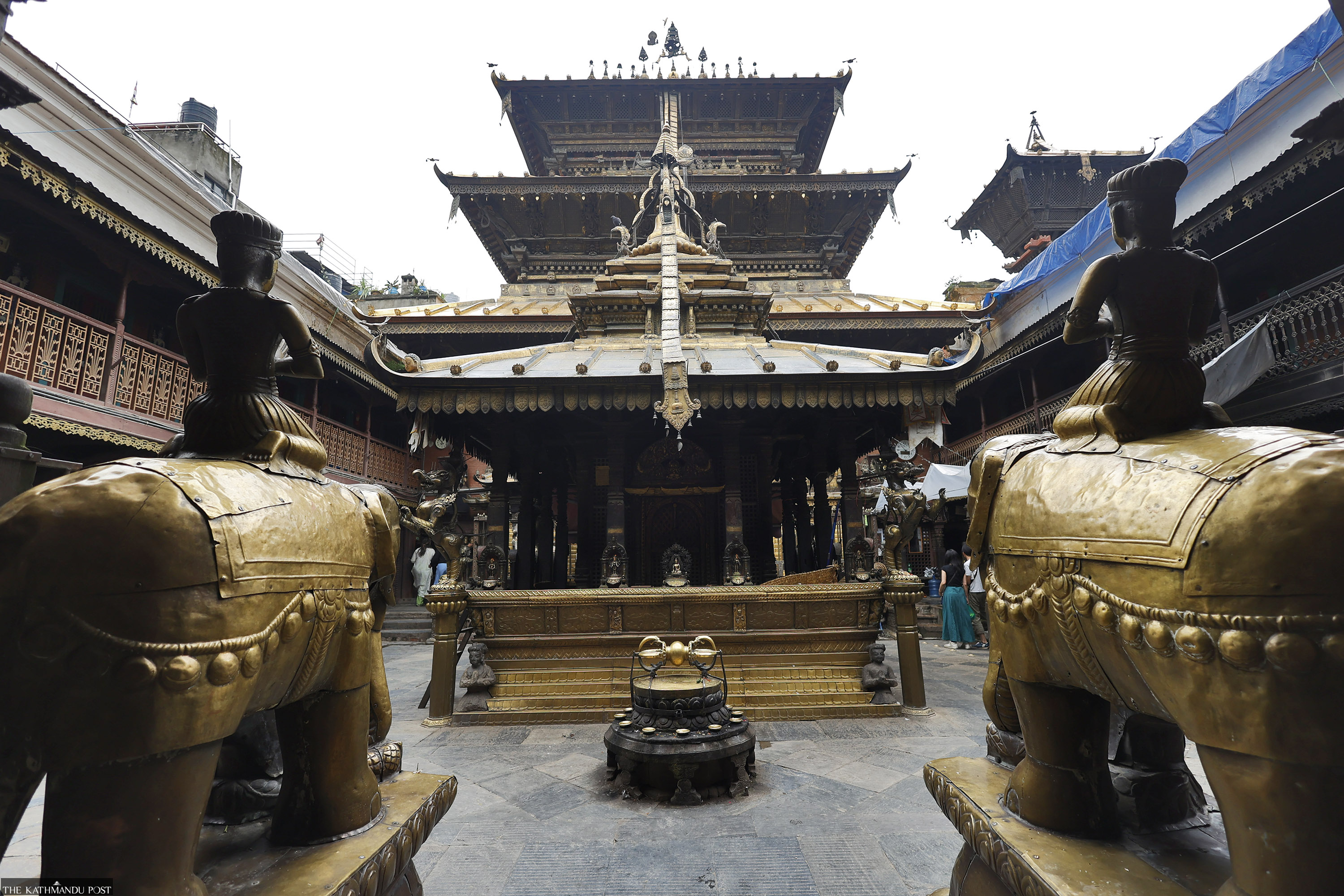

One such iconic temple is the Hiranya Varna Mahavihar at Patan Durbar Square. Colloquially known as the Golden Temple—because of its striking golden facade—Hiranya Varna Mahavihar is believed to have been built by King Bhaskar Varman sometime in the 12th century. The temple is known as ‘Kwa Baha’ in the Newa language.

Legend has it that the Mahavihar was built at the spot where a rat once chased a cat (unlike the other way around). Because of this unusual myth, rats are still fed at the site daily just before closing the temple.

As one reaches the main entrance to Kwa Baha, two stone-carved lions flank the gate. On the right-hand side, there’s a ticket counter, charging tourists a meagre fee of either Rs100 or Rs50 to witness one of the finest examples of medieval architecture Patan has to offer.

Built in a classic Newa courtyard style, also known as baha, the premises of the Hiranya Varna Mahavihar is adorned by elaborate sattals and ornate prayer wheels. In the centre rests an enshrined chaitya, believed to be of Swayambhu. In another corner, one can purchase butter lamps to offer to the gods.

As I strolled through the courtyard, I heard a group of men engrossed in conversation. Curious, I followed their voices and pulled out my camera. Seated on the sattals under the golden canopies, they were seen writing meticulously. As I moved closer, I noticed that it was a slow, trance-like process—they dipped tiny brushes into a small porcelain with liquid gold and gently applied it onto a black, rectangular paper.

The guthiyars (a member of the temple trust) were, in fact, engaged in restoring an 898-year-old manuscript called the Pragyaparamita (also known as Prajnaparamita). Pragyaparamita, in Buddhism, signifies ‘perfection of wisdom’ or ‘transcendent wisdom.’ ‘Guthi’ is a traditional Newa community trust and ‘guthiyars’ are members of that trust.

According to Hem Ratna Bajracharya, one of the guthiyars involved in the restoration, Pragyaparamita revolves around comprehending ‘Sunyata’ (which can be roughly translated to emptiness), the interconnectedness of all existence and realising the ultimate nature of reality. It is considered an important text for those on the Buddhist path as it is believed to be a recording of the 8,000 verses Gautam Budhha taught his 1,350 disciples about 2,500 years ago, and following what is written in the text can lead to bodhi or enlightenment.

Bajracharya also revealed that according to a legend, the Pragyaparamita was written by Ananda Bhikshu during the reign of King Abhaya Malla, the second Malla ruler of Nepal.

These manuscripts—lending to their age—are quite fragile and need to be restored every few years. The guthiyars use the malamaas period (also called manmaas)—a special extra month according to the Hindu lunar calendar that occurs twice every five years—to restore the texts. As ritualistic worship is limited during malamaas, the guthiyars find plenty of time (and quiet) to either re-write an entire manuscript or retrace those with damages.

The first page of this 300-page book is made up of a sizable silver plate with carved images of deities. The rest of the pages have a deep black colour and are locally known as nil-patra. This colour, Bajracharya revealed, is achieved by coating Nepali handmade paper with a solution of copper sulphate, which eventually oxidises, leaving a matte black finish.

Similarly, the gold needed for the restoration is procured with the help of donations received by the temple. “Usually, the donations aren’t enough, so members of the guthi come together and pool the rest of the money,” says Bajracharya. “The amount of gold needed usually depends on the deterioration,” says Bajracharya. “This year, we needed only 11.7 grams because there wasn’t much damage.”

According to him, the black paper serves as a perfect background for golden letters to shine through. Moreover, along with its aesthetic value, the copper sulfate coating also protects the manuscript from infestation.

The text—written in Ranjana script—is particularly tricky to master, requiring an ample amount of patience and concentration. This is why it usually takes around ten individuals—all men and members of the guthi—around 3o days to completely restore the manuscript.

This year, however, Bajracharya reveals that it only took them 25 days as the manuscript was less deteriorated than usual.

According to a report published in Nepali Times, the guthi denies any digital scans of the script as the older guthi members believe that will strip it of its tantric powers.

The Pragyaparamita is read daily by the priests at The Golden Temple. And this frequent use of the script causes the golden letters to fade over time. So, it is critical for the guthiyars to maintain and restore the textual and ritualistic aspects of the Hiranya Varna Mahavihar.

In a rapidly changing world, where ancient traditions are often at risk of fading into obscurity, it is a reminder that heritage is not static but lives on through the dedication of individuals committed to its preservation.

As Bajracharya aptly puts it, “This is an ancient ritual that has been practised by our families for centuries. So, continuing it ensures that the temple remains a living, breathing testament to our enduring cultural practices.”

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu