Koshi Province

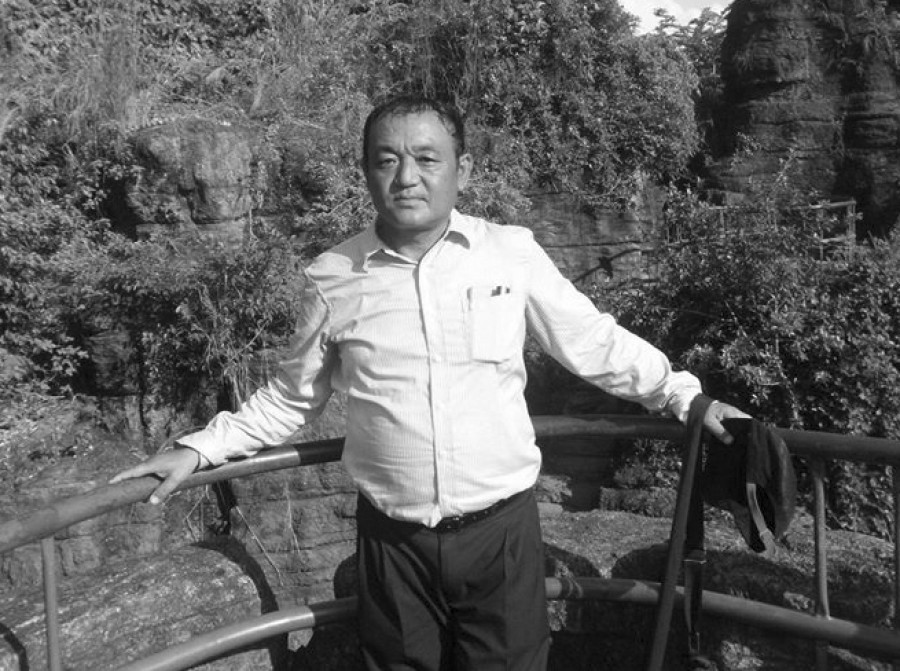

Dhyan Bahadur Rai, architect of modern Dharan, dies at 60

As mayor, Rai’s model of development has been celebrated by locals for turning Dharan into a modern, cosmopolitan city.

Pradeep Menyangbo & Dipesh Khatiwada

In the 90s, the eastern city of Dharan had a mixed reputation. It was a bastion of former British Gurkha soldiers and was known for its music, culture and fashion. But it was also a city of drug users and gang fights, says journalist Om Astha Rai, who grew up in Dharan.

“During my childhood, I saw many gang fights and petty crimes,” he said. “Dharan, which was once the zonal administrative headquarters, was a busy town, but it turned into a desolate city after the zonal government offices moved to Biratnagar after the 1990 People’s Movement.”

But slowly, as the city entered the 90s, it started to witness a renaissance. Roads were paved over, parks were built and a proper public transport system was put in place. Behind this resurgence, say many of Dharan’s residents, was one man—Dhyan Bahadur Rai, who died on Monday at the age of 60 from lung cancer.

“Dhyan Bahadur called his model the “bikash ma Dharane model” [the Dharan model of development],” said Om Astha.

Locals call Dhyan Bahadur the ‘architect of modern Dharan’. He was elected mayor of Dharan in the 1992 local elections at the age of 30 from the CPN-UML, which has now merged with the Maoist party to form the Nepal Communist Party. But he wasn’t just a political leader; Dhyan Bahadur was also an architect, a poet and an artist.

Dhyan Bahadur was born in Buipa, Khotang, and started his political career during his days studying to become an overseer at the Pulchowk Engineering Campus in Lalitpur. As an active member of leftist politics, he eventually became the Morang in-charge of the All Nepal National Free Students' Union.

But it was only when he took up a job as a teacher of a vocational trade school at Dharan’s Purbanchal Engineering Campus that he was introduced to the city he would go on to lead.

In 1992, he contested the local elections and won on a platform of turning Dharan into a city of education, health and tourism—all on the basis of people’s participation.

“He changed the entire design of Dharan after winning the election,” said Rajendra Sharma, an associate professor at the Purbanchal Engineering Campus who had known Dhyan Bahadur ever since he became mayor. “He was supported by deputy mayor Manoj Menyangbo in materialising his plans.”

Dhyan Bahadur came up with a 20-year plan to develop Dharan as a model city. Although the municipality did not have the budget required to take on development work on the scale that he had imagined, he started to blacktop roads with people’s participation. The municipality invested 60 percent of the funds while the remaining 40 percent was raised from the people. Within five years, the majority of roads in Dharan had been expanded and blacktopped.

On the basis of Dhyan Bahadur’s plan, an embankment was constructed along the Khahare river in Dharan’s Ward No 13, the Saptarangi Park constructed in Ward No 17, and a nature park in Bijaypur. Even the Phushre Public School received 35 bighas of public land.

Menyangbo, who became mayor after Dhyan Bahadur, remembers him as a leader with a mission, a vision and a goal.

“He used to believe that all stakeholders should be united to make Dharan a modern city,” Menyangbo told the Post. “He was a leader who could take prompt decisions and take action. Even the opposition did not criticise his works when he was mayor.”

Once the insurgency ended in 2006 and demands for identity swept the nation, Dhyan Bahadur defected to the Sanghiya Samajbadi Party with Ashok Rai after the 2007 Constituent Assembly elections. But that only led locals to celebrate him even more, as Dharan was part of the Limbuwan movement for representation and identity.

According to Krishna Agrawal, an economic analyst, Dharan will never forget Dhyan Bahadur’s contributions.

“He was the first leader to prepare a blueprint for Dharan’s development,” Agrawal told the Post.

Dhyan Bahadur’s final rites were performed in his hometown of Lamidanda in Khotang. He is survived by a wife and two children.

27.41°C Kathmandu

27.41°C Kathmandu