Opinion

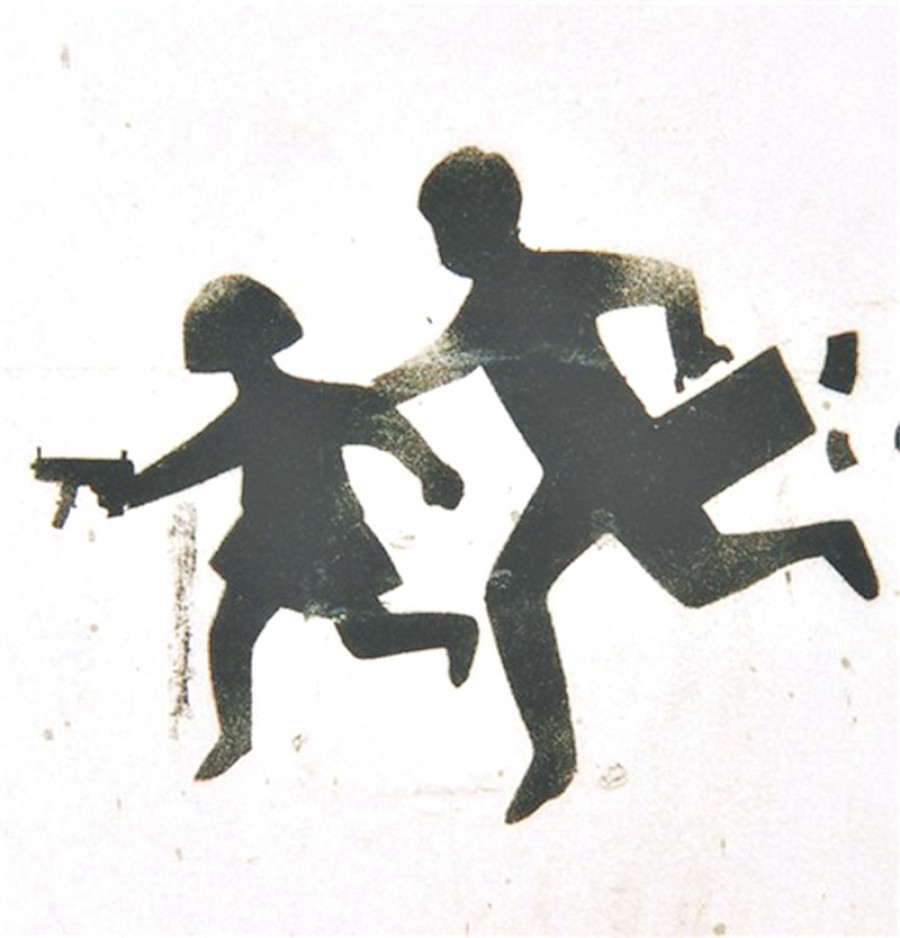

Kids with guns

Maoist child soldiers are disqualified combatants and unrecognised conflict victims

Govinda Sharma Bandi

Thousands of children joined the Maoists or were forcibly recruited during the conflict. Facing poverty and marginalisation, many of them joined to seek a better future for themselves and their families. Others joined because of victimisation. One child soldier we spoke to voluntarily enlisted in the Maoist army at the age of 11 after her father was disappeared. Another joined at the age of 13 after having witnessed atrocities in his community and hearing the Maoists talk in his village, promising to change the country by eradicating discrimination and the caste system. However, at the end of the conflict, these children were dismissed and some received reintegration training as ex-combatants, but not as victims.

Recognition is important

While child soldiers may have been involved or used in attacks by the Maoists, as a group of individuals, they have particular needs and suffered distinctive harm. Since they joined the Maoists as children, they missed out on education and other opportunities, meaning that their job opportunities are limited. Some may have suffered harm in terms of psychological distress (such as post-traumatic stress disorder) by witnessing violence at such a young age. Female child soldiers may have their own specific needs, as they may have suffered sexual violence or experienced increased stigma from the community by returning with a child that they may have given birth to while in the armed group or with a husband who may also be an ex-combatant or child soldier. This may create problems regarding inheritance or land rights that exclude these women within their community.

The issue of whether or not child soldiers are victims has been a particular source of tension for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). One child soldier told us, “I do not know if I am a victim or a perpetrator, I am waiting for the TRC to decide that.” There may be reluctance among some child soldiers to come forward to the TRC, believing that they may implicate Maoist leaders whom many former child soldiers still support despite their not fulfilling their needs. There is also a risk that advocating reparations as child soldiers may implicate senior Maoist leaders in the war crime of recruiting children to be used in armed hostilities. This is not necessarily the case. The UN Basic Principles on Reparations recognises that victims have a right to reparation even if the perpetrator is not identified or prosecuted.

Under international law, child soldiers are recognised as victims and eligible for reparations. The 2007 Paris Principles on child soldiers states that they are ‘primarily’ victims. This

does not prevent them from being prosecuted for serious crimes under international law including war crimes or crimes against humanity. Importantly, child soldiers should not be discriminated against after a conflict, and society should recognise the particular harm they have suffered. There has also been increasing efforts before the International Criminal Court and in countries like Colombia to provide appropriate reparations to child soldiers.

Appropriate reparations

Reparations are intended to publicly acknowledge and remedy the harm suffered by victims of serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law. In Colombia, child soldiers have been provided with training and minimum wages for 30 months, among other reparative measures. Measures should also be taken to provide for loss of education for children affected by the conflict. In addition, jobs should be tailored to suit child soldiers’ needs. One individual said that they wanted a job in the security forces or the army so that they could use the ‘education’ they received from the Maoists.

In terms of psychological trauma, the International Criminal Court has ordered that child soldiers only need to prove that they were in a relevant armed group to be eligible for rehabilitative psychological support. This is combined with programmes to provide livelihood support to such victims for their long-term development. Like other victims of the conflict, those who were seriously disabled after suffering a physical injury, such as losing a limb or being blinded, need access to free health services. There may also be a need to provide these seriously disabled victims with compensation to give them some financial security.

Female child soldiers should have access to specific measures to respond to their needs, in particular, access to land and housing. Apart from compensation, restitution and rehabilitation, community education should also be used to explain the harm suffered by child soldiers so as reduce their stigmatisation and empathise with their experience. Finally, Nepal needs to recognise the child soldier as a victim and guarantee that such violations do not occur again in the future. This could take the form of a law for children to be never recruited or used by the armed forces or armed groups as soldiers in Nepal. Once they are recognised, they also need to have access to appropriate reparations to ensure that they are not a lost generation.

Moffett and Sharma are associated with the AHRC’s “Reparations, Responsibility and Victimhood in Transitional societies” project

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu