Opinion

Bad men and bad laws

It has become commonplace for every government to take office promising to root out corruption

Deepak Thapa

Anyone who has been skimming the news would be aware that there are a number of power projects being delayed for one reason or another in the country. Among these is the Khimti-Dhalkebar Transmission Line, designed to carry the electricity to be generated in that region, from the much-awaited Upper Tamakoshi, and distribute it east, west or south as the demand may arise. The reasons for the delay are manifold but it has now boiled down to a few remaining individuals demanding compensation far higher than what the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA), the body responsible for building it, is willing to shell out. The government has begun making threatening noises about mobilising the army if need be to get the project moving, and there the matter rests.

In a recent conversation, a ranking NEA official expressed frustration over the

hold-up and rued the fact that the people causing the delay did not have any sense of sacrificing for the country. Had the official not said it in all earnest, it would have come across as a joke—I mean, the part about the sacrifice. It immediately got me thinking about why it should be those poor villagers in Sindhuli who had to bear such a burden when all around they can see a free-for-all. For, in the best traditions of rentiers everywhere, including most prominently in Nepali politics, they are holding out for the best deal possible and if precious electricity is being wasted by their intransigence, so be it.

Tolerance for corruption

It has become a commonplace for every government to take office promising to root out corruption. But because it is viewed as nothing more than a routine homily for governments to parrot, no one pays any serious attention to such proclamations.

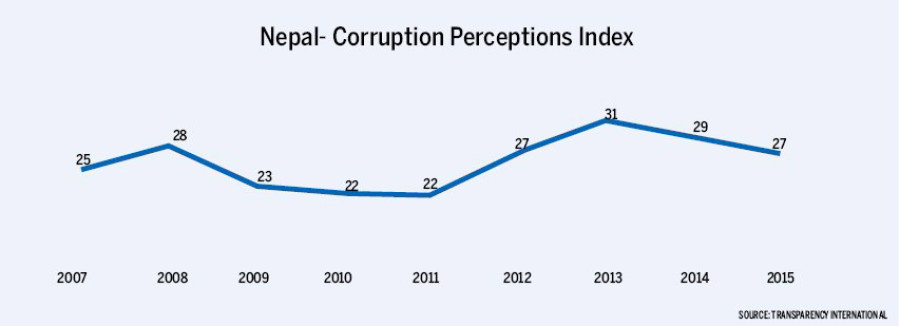

The latest report by Transparency International ranks Nepal 130th out of 168 countries in its Corruption Perceptions Index and gives it a score of 27 (out of a possible 100, compared to 91 for the least corrupt country, Denmark). The range between 20 and 30 is something we have been living with for a while now. In the years since the third coming of democracy—and leadership by all the three prominent parties—we have had our ups and downs in terms of the corruption index but more or less within the same range, as the accompanying figure shows.

One wonders if the focus of our anti-corruption measures is wholly misplaced to begin with. There have been two general strands in this regard: i) legislation; and ii) people’s empowerment. We do well enough by these standards. According to a 2015 study conducted by a team led by the former Chief Secretary, Bimal Koirala, the country ‘has 19 anti-corruption and oversight agencies, which are working directly or indirectly in curbing corruption’. That is 19 government bodies given the remit to control various forms of malpractices that can be defined as corruption. As for public awareness, a cursory glance through donor, INGO, NGO and even government reports will find mention of various initiatives such as social audits, public accountability and the like. But, evidently, going by the Transparency International reports, there is hardly anything to show for all these feel-good exercises.

The report by Koirala and team also provides a list of a number of recommendations for governments and donors to follow. Predictably, it includes further legislative strengthening of existing institutions. The 23 recommendations have also been divided into short-, medium- and long-term interventions. Tellingly, all three sections have one action in common, i.e., the use of civil society organisations in educating the public and in demanding accountability from government servants.

Words and deeds

The one element missing is something neither the donors can do anything about nor is in the interest of the government: political will. Some 10 years ago, my friend,

journalist Mohan Mainali, had written about an interesting exchange he had

had with the Director of Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, Chua Cher Yak. Asked half in jest if his agency would consider taking on contract the administration of our own Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), Yak turned all serious and told the visiting Nepali delegation that just like cleaning the stairs, a country’s corruption has to be swept from the very top and that it was a waste of time to begin at the bottom. Hence, my earlier point that if after two decades we cannot break out of the 30th percentile in the corruption perception index, empowerment at the grassroots is just so much good money and effort down the drain.

Let us look at our record at tackling corruption at the leadership level. The one and only time post-1990 era politicians were convicted, since all of them happened to be either current or former Nepali Congress leaders, instead of taking the opportunity to purge individuals hurting its reputation and taking the moral high ground, the party decided to view it simply as a case of political vendetta. And, rehabilitation of the corrupt was immediate with the reception following their release of a kind generally reserved for returning heroes. The party does not appear to have a stated or unstated policy on how to deal with those convicted of such crimes against the people, and neither it seems the party rank and file, for the latter ended up handing one of the former jailbirds, Khum Bahadur Khadka, a resounding victory at the just-concluded general convention.

In his 11 years in office, Yak proved to be a highly respected voice in the fight against corruption, and it is a measure of his track record that Singapore retains the bright spot of being the least corrupt Asian country, with a worldwide rank of eight and a score of 85. For the sake of comparison, close neighbours, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia, stand at 54, 76 and 88, respectively, a clear indication that something other than culture is at work here. He states a truism that one wishes so dearly for our own country: ‘Our job is driven by political will. We can only be as effective as the Government wants us to be.’

Elsewhere, he writes, ‘genuine political will has to be more than some pious

rhetoric, some empty sloganeering. Words must match deeds. There has to be a

sincerity of purpose and the all important display of personal example.’ And,

apparently, both need to go hand-in-hand. Remember, Sushil Koirala was an example of personal probity. But his oft-repeated warning of ‘zero-tolerance’ towards corruption remained nothing more than ‘pious rhetoric’ since he lacked that crucial element of political will.

To conclude with Yak, he writes: ‘An ancient Chinese official once said that corruption is the product of bad men and bad laws. If this be so, the formula must then be a frightfully simple one: have good men and have good laws.’ The laws have never been a problem in Nepal. If only we could find a way of getting rid of the bad men and women! For the moment, that can be no more than wishful thinking.

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)