Columns

HDI and development delusion

There is little reason to be confident that the remittance economy will endure in the long term.

Naresh Koirala

The hopes of Nepalis for rapid economic development, inspired by the Republican constitution (2006), have turned into despair. A widespread sense of despondency, often expressed as “nothing happens in Nepal,” pervades the country. Nepal’s overall official unemployment rate rose from approximately 5 percent in the mid-1990s to about 11 percent—one of the highest in South Asia—in 2024. Unemployment among the working-age population is the highest and worsening; it increased from approximately 7 percent in 1995 to about 23 percent in 2023. Hundreds of young men and women leave the country every day for employment. The phrase “Our villages are becoming empty” is a common outcry. Large areas of farmland lie fallow because there are no young people to work in the fields.

A report published by the International Labour Organisation, Asian Development Bank, and OECD in 2024 concluded that the number of migrants from Nepal increased by 102 percent between 2019 and 2022, the highest increase in migration outflow among the 13 South and Southeast countries they studied.

Once a food-exporting country, Nepal is now an importer of everything, including food. Widening trade deficit is a recurring pattern. In 2011, it was approximately $4.5 billion. In 2024, it rose to approximately $12 billion and is projected to increase further.

Ordinary citizens hold political leaders of the three major parties, who have governed the country in turns since 2006, responsible for the state of the country. However, these leaders and their supporters argue that anti-republican, anti-democratic elements are spreading lies, citing Nepal’s improvement in the Human Development Index (HDI) over the last few decades as proof of “our achievement.” They refer to their critics as “negativists” and the “nothing ever happens here” sentiment as “negativism.”

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a composite measure used by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to evaluate a nation’s average progress across three key dimensions: health, education and income. The 2023 HDI Report highlighted “significant improvements” in Nepal’s Human Development Indicators between 1990 and 2022: life expectancy at birth increased from 54.4 to 71.45; mean years of schooling rose from 2.0 to 5.1 years; Gross National Income (GNI) per capita (PPP$) grew from $1,372 to $3,877, and the HDI increased from 0.387 to 0.602. (The highest HDI score any country can attain is 1.0). Nepal is on track to graduate from the ‘Least Developed’ to the ‘Developing’ category in November 2026.

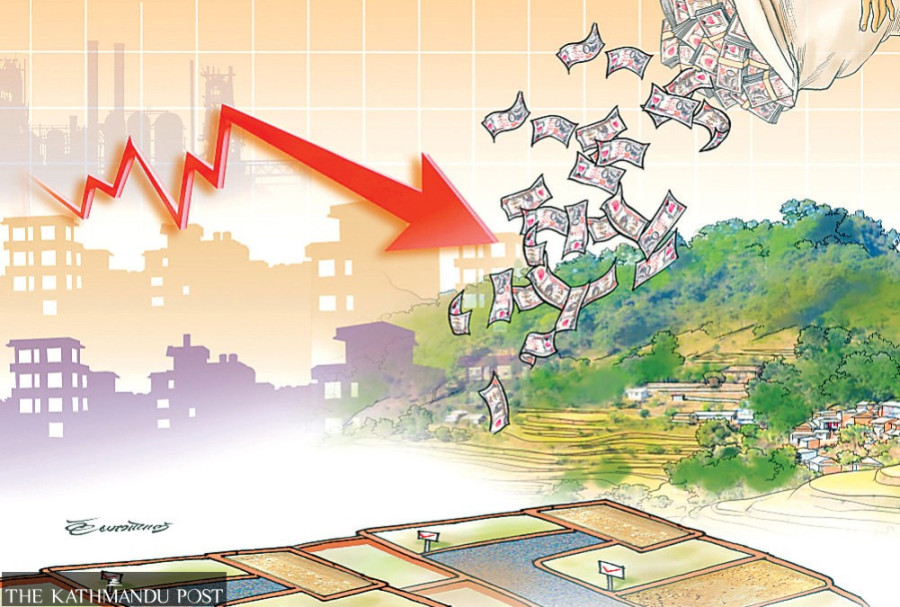

At first glance, the rise in HDI is impressive. But it has been built on remittances from poor migrant labour and development assistance provided by rich countries. It does not reflect the country’s long-term economic health. Nepal has been the poorest country in South Asia for a long time and remains so.

The improvement in HDI reflects a global trend. Taken out of context, it masks the looming threat of economic collapse hanging over the country. Politicians should ask whether the current economy is sustainable and devise plans for domestic job growth and economic development rather than gloating over the HDI improvement.

Sustainability issues

The remittances from the migrants sustain the current economy. According to the UN Migration report of June 2024, “with over 2 million Nepalese living abroad, Nepal relies heavily on their remittances. In 2023, Nepal received around USD 11 billion in remittances, which accounted for more than 26 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product, exceeding the combined inflow of official development assistance and foreign direct investment.”

The World Bank report of June 18, 2025, states: “Nepal’s reliance on remittances—which has been such an important element in the country’s poverty reduction story—has been central to the country’s growth but has not translated into quality jobs at home, reinforcing a cycle of lost opportunities and the continued departure of many Nepalis abroad in search of employment.”

The Bank’s comments constitute a veiled warning that unless the government takes concrete actions to create domestic jobs, the economy will be unsustainable in the long term. And there are several domestic factors and global trends, not considered in the Bank’s report, that will negatively impact the remittance economy.

Domestic factors: It has become public knowledge that working conditions abroad are extremely harsh and that manpower supply agencies, often in collusion with political leaders, are highly exploitative, provoking widespread public outrage. The government has so far ignored public demands for an investigation into those involved in “human-trafficking scandals,” but it may not be able to do so for much longer. Once an investigation begins, a notable decrease in migrant outflows is inevitable. The decline in migrants leaving Tribhuvan International Airport following the “visit visa” scandal—an incident involving human trafficking and corruption orchestrated by immigration officials in collusion with manpower agencies to permit illegal migration—has demonstrated this point.

Global trends: The anticipated decline in development aid from all donor countries, combined with rising anti-immigrant sentiments in wealthy nations, is bound to reduce remittances and severely harm the economy.

Overall, there is little reason to be confident that the remittance economy will endure in the long term.

Job growth and development

In the current budget, the allocation for capital expenses is less than 20 percent; agriculture’s share is even less. Given the long-standing history of underspending on capital expenditure, the actual spending in 2025-2026 is likely to be around 8 percent of the total budget. To expect long-term job growth and sustainable economic development with such measly investment is delusional. The government believes there are insufficient funds to allocate to development; paying for recurring expenses consumes most of the country’s budget.

Nepal is not the only country facing development fund constraints. Other nations, including India and China, also encountered funding difficulties during their early development stages. They addressed this by creating an environment that attracts Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Over the years, Nepal has also introduced several legal and institutional measures purportedly designed to attract FDI. However, these efforts have failed; instead of increasing, our FDI has declined. According to a recent report published in this newspaper, Nepal’s FDI has decreased by 70 percent over the past six years. It fell from $185 million in 2019 to $57 million in 2024.

Why has Nepal not been able to attract FDI, while China and India could? Potential investors trust China’s and India’s assurances of investment security in their countries. No reputable investor trusts the Nepali government and its leaders’ assurances due to the high level of politicisation, even of the organs of checks and balances, and the pervasive political corruption that has seized the country.

The only way to earn investors’ confidence is to demonstrate by action, not just empty words, that our public institutions are transparent and independent, and that the government and its leaders operate with integrity. In contemporary Nepal, that sounds like a fairy tale, but unless it is turned into a reality, this remittance-based economy will never be far from potential economic collapse. Arguing that the improvement in HDI, driven by remittances from the poorest in the country, is a measure of the country’s economic success is not just delusional, but also deceitful.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu