Opinion

The man from Limbuwan

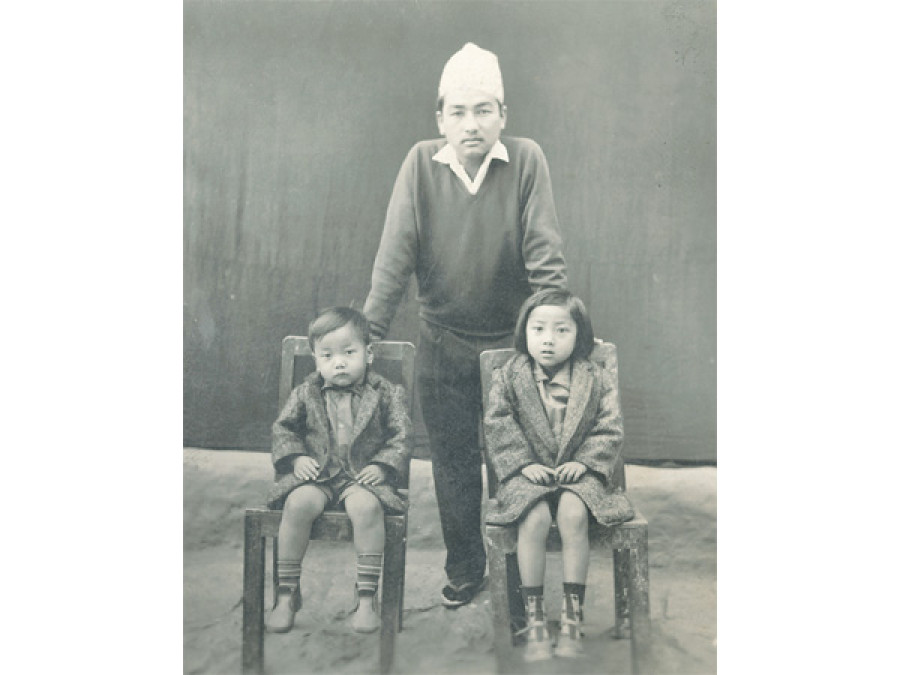

A tribute to my father Padma Sundar Lawoti

Surendra Lawoti

After my dad passed away last June, my sister Gurans and my brother Mahendra dug out the many photo albums that were stored away in our house in Gwarko, Lalitpur. They were 20 or so albums and easily few thousand photographs—mostly 4x6 colour prints and some smaller black and whites that were much older. It seemed each of us five siblings had our own albums—of our youth, our studies abroad, of picnics in Godavari or Nagarkot, our travels, our few sports triumphs, and of festivals with all of us together. It was comforting to go through the pages of these albums. It brought us back to our lives that we had left behind, forgotten and traversed to such distant places as the UK, America and Canada. And during the time of our loss, the photo albums helped us ground ourselves.

Man of the people

My dad, Padma Sundar Lawoti was born in Quetta in Baluchistan province of Pakistan when my great maternal grandfather was stationed there as a Captain in the Gurkha forces. When my dad was only a year and half old, my grandfather passed away. My grandmother was sixteen. After my grandfather’s death, my grandmother’s maternal family took it to raising and schooling of my dad in Jaljaley Phongdin in Terhathum. My dad’s schooling took him to Dhankuta, Dharan and later on to Lainchaur School in Kathmandu, where he completed his high school. Dad never took it to academics. Perhaps he was too radical for academic constraints. After his schooling stints, he returned to our village in Yashok, Panchthar in 2014 BS, and laid the foundations for his political career that would span over 50 years.

One of the first things my dad did in Yashok was to establish a post office called Siddhadevi Janata Hulak. During that time, the only post office in the region was in Terhathum, a hard day’s walk away. My dad hired a courier at Rs 8 per week. The courier would carry all the letters and walk to Terhathum every Friday on the day of haat bazaar. On return he would bring back letters. At Yashok, haat bazaars took place every fortnight, on days of the full moon and the new moon. People from neighbouring villages attended the bazaar for shopping, commerce, official business and for pleasure. During the haat bazaars, my dad would go around distributing the letters. Since he lived most of his youth away in his maternal home, people did not know him. People would ask: “Who is this young man delivering letters?” Some would say: “He is the grandson of Sher Bahadur Subba.” My great grandfather Sher Bahadur was a well-respected figure for his philanthropy. Through the establishment of the post office, my dad was able to connect with people. He understood early on that to serve as a public officer, one has to have strong connection to people at the ground level.

Man of many shades

Dad was quite a character with some peculiar and admirable traits. He was fearless. He was smart as a whip and witty as hell. He was a ferocious orator and his opponents did not enjoy being at the receiving end during debates, especially in the Rastriya Panchayat Parliament. He was the hardest working person I have ever known. Once he set his mind on something, he worked at it doggedly. He also had strong held convictions and to some extent to a fault. To my knowledge, he never consumed alcohol or smoked cigarettes. Most importantly, he enjoyed being among people, which helped him maintain strong relationships with his constituency. From his habits before the mobile phone era, he knew phone numbers of his contacts by heart. While his assistants fiddled with phone books or their mobile phones to find a number, he could recall a number off the top of his head. He was an early riser and I remember him calling people in the villages to see how things were. He would know if it had rained in different parts of Panchthar or Jhapa. He would know if the drinking water pipes were broken in a particular ward. With these traits, he went on to become minister for 12 times including Agriculture Minister in the Sher Bahadur Dueba coalition government post-1990. It is quite a journey for a man from Limbuwan, a region far away and detached from the power centres in Kathmandu.

The most powerful portfolio he held was that of a Home Minister in the Lokendra Bahadur Chand government. Despite being a Limbu from relatively humble background, he rubbed shoulders with some of the Panchayat political elites. But I have always wondered if he felt like an outsider among the Shahs, the Ranas, the Thapas, and the Chands who were all traditional royal courtiers. His ways were brash compared to the ‘jinar garibakshiyo’ crowd. He was not as educated as they were. He was a touchable ‘matwali’. Perhaps recognising these differences, he had to carve a space for himself. He was a fiercely vocal and opinionated person. And he would never back away from a fight. He was falsely branded as being communal and the leader of ‘Shetamagurali’ (Sherpa, Tamang, Magar, Gurung, Rai and Limbu) during the Panchayat regime. He was also accused of treating people differently based upon the length of people’s noses—meaning he favoured shorter-nosed Janajatis over the longer-nosed Brahmins. Yes, he was vocal about Janajati and minority rights, but the accusation was false. .

Born for politics

Yet, it fascinates me to see the course of his convictions with regard to ceremonial monarchy and Nepal’s identity as a Hindu state. Two People’s movements came and went. So did the ten-year long Maoist insurgency and the two Madhes movements. Some of his Panchayat colleagues such as Surya Bahadur Thapa and Pashupati Shumsher Rana have abandoned monarchy in their party manifestos. Even Kamal Thapa seems to have sidelined the agenda of constitutional monarchy and seems focused on reinstating Nepal as a Hindu state. But my dad, the touchable matwali, vehemently championed for constitutional monarchy and a Hindu state until his last breath.

My dad was one of those who would be politically active from his hospital bed, whether it was the Medanta Hospital in New Delhi or the Norvic Hospital in Kathmandu, against doctors’ and family members’ objections. He was doing politics from his bed in Norvic the day before he passed away. Politics was in his blood. He believed in serving the people from Panchthar and the Limbuwan region. On the love of Panchthar, he wrote in his autobiography published few months before his death: “No matter which corner of the world I am in, I always dream of Panchthar.” He dedicated his entire adult life for the region he loved so much. He went through many ups and downs in his career. As a son, it comforts me to know that he gave everything for his community. I am certain the people of Limbuwan will warmly remember him. And I feel fortunate to have such a courageous man as my father, for when I am in need of courage I think of him.

Lawoti is a Nepali photographer based in Toronto. His solo exhibition The Man From Limbuwan pays tribute to his father late Padma Sundar Lawoti, which will be on display at Image Ark in Patan, part of Photo Kathmandu from Nov 3 to 9, 2015

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu