National

Cyabra report on Nepal Gen Z protest comes under scrutiny

It makes claims about fake accounts without defining ‘fake’ or ‘inauthentic’ profile.

Aarati Ray

A new report on Nepal’s Gen Z-led protests prepared by Cyabra, an Israel-based artificial intelligence firm that tracks misinformation online, has ignited controversy.

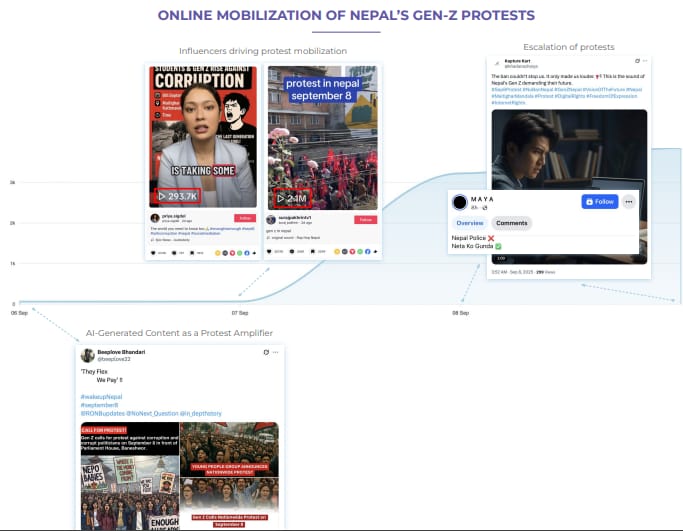

The report, titled “Nepal Protests 2025: Online Narratives and Fake Profile Influence”, examined conversations across X, Facebook, and TikTok between September 6 and 9. (The Gen Z uprising took place on September 8 and 9.)

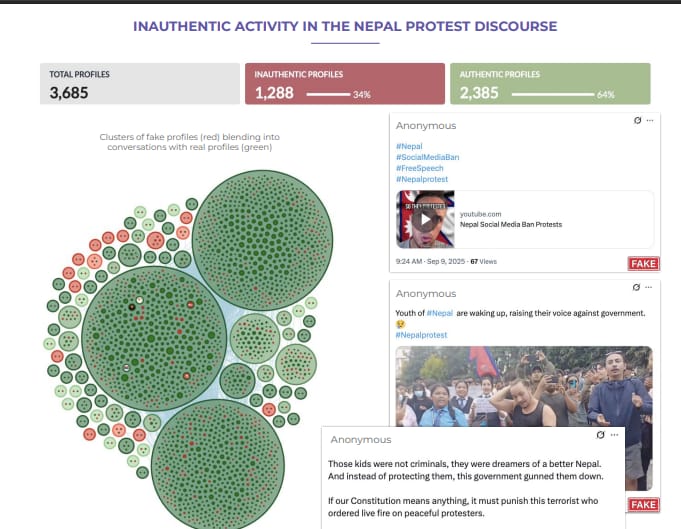

Cyabra said its AI-driven analysis found that inauthentic accounts made up 34 percent of the sampled 3,685 profiles on X. The report states that the coordinated use of hashtags, deliberate interaction with real users, and their role in generating 11.5 percent of total engagements and 14 percent of potential reach illustrate how fake accounts can influence narratives and amplify protest messages far beyond their organic audience.

Soon after the report’s release, online discussions distorted its findings, with some users claiming that the protests were fully orchestrated by fake profiles or driven by external actors.

Digital experts have pushed back against those interpretations, calling them misleading. While the report may offer some indications or insights, experts emphasise that it cannot be treated as definitive evidence because of its shortcomings.

What does the report say?

Cyabra analysed a research sample of 3,935 profiles that generated more than 7,200 posts and comments. By scanning participating profiles for signs of manipulation and influence operations, the firm identified 1,288 ‘inauthentic’ accounts operating on X—around 34 percent of the sampled 3,685 users on that platform.

These accounts, the report found, spread content in tandem with authentic users (2,385), reinforcing claims against the government and police while actively promoting the protests and calling on others to join.

Inauthentic profiles also used the same hashtags as real users, including #NepalProtest, #GenZProtest, #SocialMediaBan, and #EnoughIsEnough, to push protest narratives.

While ‘authentic’ users drove most of the online protest activity, Cyabra said fake profiles played a disproportionately powerful role in amplifying key messages. They accounted for about 11.5 percent of total engagements, more than 164,000 interactions out of 1.4 million, and reached an estimated 326 million potential views, or roughly 14 percent of the total potential reach.

Although a minority in number, the report said, these accounts strategically inserted themselves into real conversations, helping protest narratives appear more widespread and organic than they actually were.

Expert analysis

Ujjwal Acharya, director of the CMR Nepal Journalism Academy and project coordinator of NepalFactCheck.org, an IFCN-certified fact-checking initiative in Nepal, says the report lacks methodological transparency.

While the report mentions the use of artificial intelligence, it does not specify what kind of AI model was employed, nor does it clearly outline its methodology or analytical tools, along with sampling method and dataset. “We should critically analyse the report as it lacks transparency,” he said.

Acharya added that while civil society, government agencies, and other concerned stakeholders can take the research as a starting point, its findings should not be taken as absolute facts.

“The report is interesting, but it doesn’t resemble the work of an academic research institution,” said Rajib Subba, former deputy inspector general of Nepal Police, who is a cybersecurity expert with a doctorate in communications and information sciences. “It feels more like a product of a private cybersecurity company seeking visibility or mileage.”

Subba, also a cybersecurity researcher at Madan Bhandari University of Science and Technology, further noted that while the report makes several claims,it lacks sufficient depth in explaining why or how those events took place.

The report makes claims about fake accounts without defining what constitutes a ‘fake’ or ‘inauthentic’ profile. It remains unclear whether these accounts were bots, parody pages, troll accounts, pseudo-activist profiles, or simply anonymous users.

The report’s section titled ‘Inauthentic activity in the Nepal protest discourse’ states that out of 3,685 profiles, 34 percent were inauthentic. Yet no dataset or spreadsheet of those profiles has been made available for independent review.

There are only three screenshots of anonymous posts labelled ‘fake’ in red, which gives rise to confusion about what exactly they considered fake or inauthentic.

From the examples and screenshots included in the report, it appears that the report may have categorised anonymous accounts or posts as inauthentic.

But experts believe all anonymous accounts can’t be assumed as fake or inauthentic.

Subba says, considering Nepal’s political climate and even global contexts, not everyone feels safe expressing their opinions openly on social media. They may choose anonymity to avoid potential risks to their job, safety, or personal life.

“So, it would be wrong to label all anonymous accounts as inauthentic. These kinds of clarifications are missing from the report,” added Subba.

The report’s time frame—between September 6 and September 9—is too narrow. “We need to think whether content from those specific days can truly capture the entire narrative of the Gen Z movement,” Acharya said.

While the report has some limitations, experts acknowledge that it also highlights that digital activism was an important part of the Gen Z protest movement.

At the same time, the report reinforces how social media is a double-edged sword.

“It points to how our information ecosystem is vulnerable,” Acharya said. “If malicious actors want to manipulate it. There are enough opportunities and openings for them to do so.”

Another major weakness of the report is its failure to distinguish between spontaneous digital activity and coordinated inauthentic behaviour.

“The real threat arises when accounts are ‘coordinated inauthentic behaviour’ to manipulate narratives,” said Subba. “Whether or not that was the case during the Gen Z movement remains unclear, and it is the report’s weakest point.”

Coordinated inauthentic behaviour (CIB) can involve fake accounts, real accounts used deceptively, or a mix of both. It is typically aimed at manipulating public opinion, artificially boosting content with chatbots, or running influence operations for political, strategic or financial ends.

Social media platforms have guidelines to minimise such CIB. In doing so, they look at coordinated activity from multiple accounts rather than individual anonymous accounts. The Cyabra report, however, focuses on single anonymous or spontaneous profiles and does not clarify whether it identified coordinated networks.

It also fails to distinguish whether there were automated bots or human-run anonymous accounts. Bots pose higher risks due to automatic amplification, while one person managing multiple accounts, for work, personal use, or parody, does not constitute coordinated inauthentic behaviour . Without this distinction, claims like 34 percent of profiles being “inauthentic” could be an overstatement, says Acharya.

Acharya also has reservations about the report’s claims that fake profiles drove 11.5 percent of engagements and reached 326 million potential views. According to him, engagement does not necessarily indicate real-world impact, as online activity may not translate into offline influence. Without evidence linking online activity to tangible offline effects, engagement metrics can only tell part of the story.

Another point of concern is Cyabra itself. The company is not a long-established or widely recognised research institution, and even the report’s authorship remains unclear. Its previous publications have seen limited international citation or recognition. Cyabra was reportedly founded in 2017 by Dan Brahmy, Yossef Daar, and Ido Shraga, all former members of Israel’s elite intelligence units.

“Just because a foreign organisation publishes something doesn’t mean it should be accepted without scrutiny,” said Acharya. He added that the fact that an Israeli private firm released a report on Nepal’s protests so quickly, and without involving any local experts or researchers, is something that warrants critical examination.

Moreover, the report appears to overlook crucial local factors, such as Nepali hashtags, language nuances, metaphors, and cultural context, that shape online discourse. “Nepal’s protest narratives are deeply rooted in local emotions and expressions, which cannot be directly compared with movements elsewhere,” Subba noted, calling the analysis ‘superficial’ as a result.

“The spread of rumours and disinformation during protests is not new in Nepal. What has changed is the medium, moving online,” said Subba. “The key question is not whether fake information was circulated in the protest, but whether it was coordinated, collaborative disinformation or simply spontaneous digital activity. This is what needs to be researched.”

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu