National

A six-point primer on past and present of Lipulekh controversy

India and China have once again alarmed Nepal by agreeing to conduct trade through the Lipulekh Pass without informing Kathmandu. For over a decade, China and India have taken up the issue bilaterally, disregarding Nepal’s sensitivities.

Rajesh Mishra

Ever since Indian troops occupied Kalapani in 1962, the matter has troubled Nepal. Here is an explainer on the six-decade-long history of the dispute.

Where are Kalapani, Lipulekh, and Limpiyadhura?

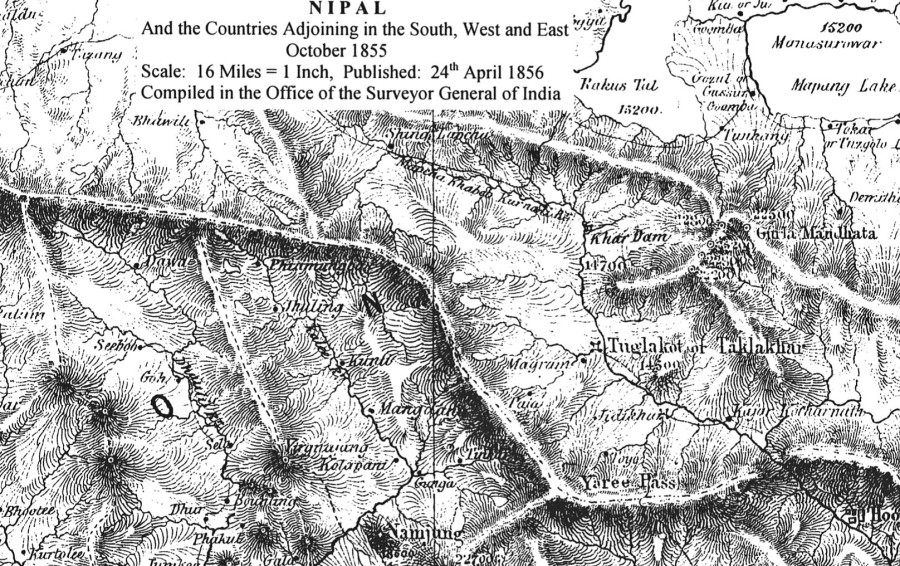

The 1816 Sugauli Treaty fixed the Kali River as Nepal’s western border. Since the river originates in Limpiyadhura, all land east of it—including Kalapani and Lipulekh—belongs to Nepal. Yet a 370 sq km area in Byas Rural Municipality is under India’s Pithoragarh District.

Kalapani lies at an elevation of 3,600m, Lipulekh at 5,115m, and Limpiyadhura at 5,500m. Lipulekh was historically a trade and pilgrimage route to Mansarovar, but Nepalis can now only go 22 km short of the pass. India controls the entry gate at Kalapani and has stationed troops there year-round since 1962.

India claims the Lipukhola, a tributary east of Limpiyadhura, is the Kali, and on this basis it occupies the 370 sq km area. Indian forces even built a Kali temple there to bolster their claim.

What is the strategic and commercial importance of Lipulekh?

Settlements like Tulsinyurang, Gunji, Kuti, and Nabi lie along the Kali basin, but Nepal’s access now reaches only up to Chhangru. From Chhangru, Kalapani lies about 12 km uphill, and 10 km further above Kalapani lies Lipulekh Pass on the Chinese border.

India uses Kalapani valley to monitor China, while Lipulekh provides it with a shorter trade and pilgrimage route to Kailash Mansarovar. China, for its part, sees the pass as a gateway to India’s vast market.

“Lipulekh is a strategic and military hub. India has used it to calibrate its security and military relations with China,” says Bishnu Raj Upreti, chair of the committee formed five years ago to study the issue of Limpiyadhura, Kalapani, and Lipulekh. “Commercially, China also considers the route useful.”

King Mahendra’s silence

Although old maps confirm Limpiyadhura as the Kali’s source, India occupied Kalapani during the 1962 war. King Mahendra chose not to contest it immediately, fearing it would look like siding with China.

Former foreign minister Bhek Bahadur Thapa has confirmed King Mahendra’s awareness of the Indian troops entering Kalapani during the 1962 India–China war.

In his book Rashtra–Pararashtra, he writes: “At the height of the 1962 war, Indians deployed troops in Kalapani. This matter reached King Mahendra. He said: ‘Right now India and China are at war. If we raise this issue now, it will look like we are taking sides. We should raise it after the war and seek a solution.’”

Later, even after Indian troops withdrew from other northern border posts in 1969, they stayed in Kalapani.

Failure of border committees to resolve the issue

From the 1980s to today, various Nepal–India mechanisms addressed border disputes but left Kalapani, Lipulekh, and Susta unresolved. Successive prime ministers pledged dialogue, most recently in 2022 and 2023, but talks never materialised.

India, China fuel controversy

In May 2015, India and China agreed to expand border trade through Lipulekh without consulting Nepal, sparking protests.

When Indian PM Narendra Modi visited China on May 14, 2015, an unexpected agreement appeared in his talks with Premier Li Keqiang: “Both sides agreed to expand border trade through Nathula, Qiangla/Lipulekh Pass, and Shipki La Pass.”

This meant using Lipulekh—Nepali land—for trade without any consultation with Kathmandu. The then-government under Sushil Koirala sent formal objections to both China and India.

International relations expert Bishnu Raj Upreti says it was the first time Nepal took a strong stand, declaring Limpiyadhura, Kalapani and Lipulekh as its own territory. “From that point, the encroachment of 370 sq km by India was also internationalised,” he says.

Nepal objected formally and later issued an updated official map in 2020, including

Limpiyadhura, Kalapani, and Lipulekh. Despite this, China’s 2023 map showed the area as Indian territory. India’s 2019 map incorporated Kalapani and Lipulekh, followed by a road inauguration in 2020. Nepal protested and issued its new “Chuche Map,” approved by Parliament.

What now?

Prime Minister KP Oli, who is set to visit China and India later this month and next month, respectively, faces pressure to raise the issue. Nepal’s Foreign Ministry has already expressed dissatisfaction, while India maintains Lipulekh trade dates back to 1954 and rejects Nepal’s claims.

Since Nepal has historical evidence that Limpiyadhura, Lipulekh, and Kalapani are its territory, Upreti says the government must speak firmly with proof to both neighbours.

“How could they agree to use our land for trade without even involving us? We have the evidence. China too has failed to play a constructive role,” he says. “Prime Minister Oli is preparing to visit both countries. He should raise Nepal’s concerns with evidence.”

Prime Minister Oli is scheduled to visit both China and India in the near future. He will attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization meeting in Tianjin, China on August 31–September 1, and later pay an official visit to India starting September 16.

14.29°C Kathmandu

14.29°C Kathmandu