National

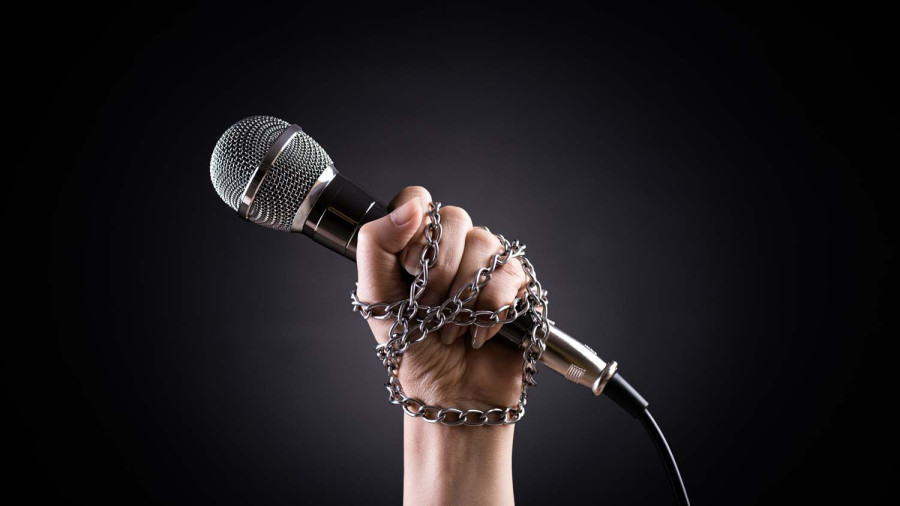

IT and Cybersecurity bill raises free speech concerns

The bill aims to consolidate and modernise laws governing technology, digital records, and cybersecurity.

Post Report

The ‘Information Technology and Cybersecurity Bill-2082’ has raised concerns among digital rights advocates over free speech, data privacy, and gaps in cybercrime provisions.

The bill, registered in the House of Representatives on June 10 and tabled by the minister for communications and information technology on August 14, aims to consolidate and modernise laws governing technology, digital records, and cybersecurity.

It also looks to regulate cyberspace, strengthen the authenticity of electronic documents, and replace the outdated ‘Electronic Transactions Act, 2063’.

The bill has been open for a 72-hour period to submit amendment proposals since Thursday.

Digital Rights Nepal released an analysis report on the bill on Friday, warning that many provisions are vague, broad, and incomplete, which put the bill’s objectives and constitutional basis under question.

Santosh Sigdel, executive director of Digital Rights Nepal, said that although the bill includes some important and positive measures, it needs more clarity and improvements to address issues related to privacy, freedom of expression, and digital rights protection.

One of the most contentious provisions, the analysis report notes, is Clause 88(1), which prohibits producing, collecting, distributing, publishing, broadcasting, or displaying ‘obscene material’ via any electronic system. The clause carries penalties of up to two years in prison, fines of up to two lakh rupees, or both.

But the bill does not define what constitutes ‘obscene material’. This absence of a legal definition, the report says, opens the door to arbitrary enforcement.

“Obscenity is a subjective concept, varying across social, cultural, and legal contexts. Without clear criteria, regulators could interpret the term in ways that target journalists, citizens, or artists for legitimate expression,” reads the report.

Another clause, 61, requires that entities collecting personal data inform individuals about its use, limit its application to the stated purpose, and destroy it within 35 days after that purpose ends.

While these are positive steps, Digital Rights Nepal notes that the bill leaves out fundamental rights for data subjects, such as the right to access, correct, delete, or object to the misuse of their data.

The bill also has no detailed rules for cross-border data transfers, and a complaint mechanism for people harmed by such data breaches.

Another omission, according to the analysis, is the lack of explicit provisions addressing technology-facilitated gender-based violence.

The existing Electronic Transactions Act has long been criticised for failing to tackle offences such as cyberstalking, cyberbullying, sextortion, and online harassment. The new bill does not address these crimes either.

The report highlights that this is a missed opportunity to respond to the growing number of women and girls targeted through digital platforms, often with severe psychological and reputational harm.

The bill’s limited and outdated definition of cybercrimes is yet another critical gap, as per the analysis.

Based on the data from Cyberbureau, Nepal has seen a surge in online financial fraud, identity theft, data breaches, social media misuse, and the spread of misinformation.

Yet the bill does not explicitly include crimes committed on social media within its scope. Nor does it align its cybercrime definitions with the United Nations Convention against Cybercrime, adopted on 24 December last year and soon to come into force, which Nepal will be obliged to follow.

Digital Rights Nepal says aligning the law with international standards now would avoid the need for rapid amendments later and ensure more effective enforcement.

The group also calls for explicit mention of social media within the cybercrime section and for penalties to have both minimum and maximum limits to ensure proportionality.

By not adopting minimum sentencing thresholds, the bill leaves wide discretion to judges and risks inconsistencies in punishment for similar offences.

The report concludes that the bill needs thorough stakeholder consultation and amendments to ensure legal clarity, safeguard human rights, and encourage technological development.

8.79°C Kathmandu

8.79°C Kathmandu