National

The postman does not ring—not even once

Once a lifeline, postal service sees a gradual death, with not many letters to deliver while the revenue is falling.

Anup Ojha

On a recent afternoon, Chiran Khatri was all set to head to load a sack of letters onto his motorbike to be dropped to the addressees.

“It’s not as heavy as it used to be in the past,” said Khatri, 56, a postman for three decades. “It won’t take long to deliver them.”

According to him, almost all the letters are official ones—court or insurance related or from one government office to another.

“Since the internet arrived, people have stopped writing letters,” said Khatri, who was spotted at the General Post Office, Dilli Bazaar.

Khatri is one of the 91 postmen working for the General Post Office in Kathmandu.

Shree Prasad Khanal, 50, also a postman for the past 28 years, echoes Khatri.

“We used to be overwhelmed by the sheer bulk of letters that we used to see until two decades ago,” said Khanal. “But we don’t have much work these days. There are just a handful of letters that we need to drop.”

Before the internet, or the mobile internet in particular, the postal service used to be a vital link for people across the country. It was impossible to imagine life without the postal service.

According to both Khatri and Khanal, there used to be so many letters to deliver in a day that sometimes they would struggle, at times working on even Saturdays, the weekly holiday.

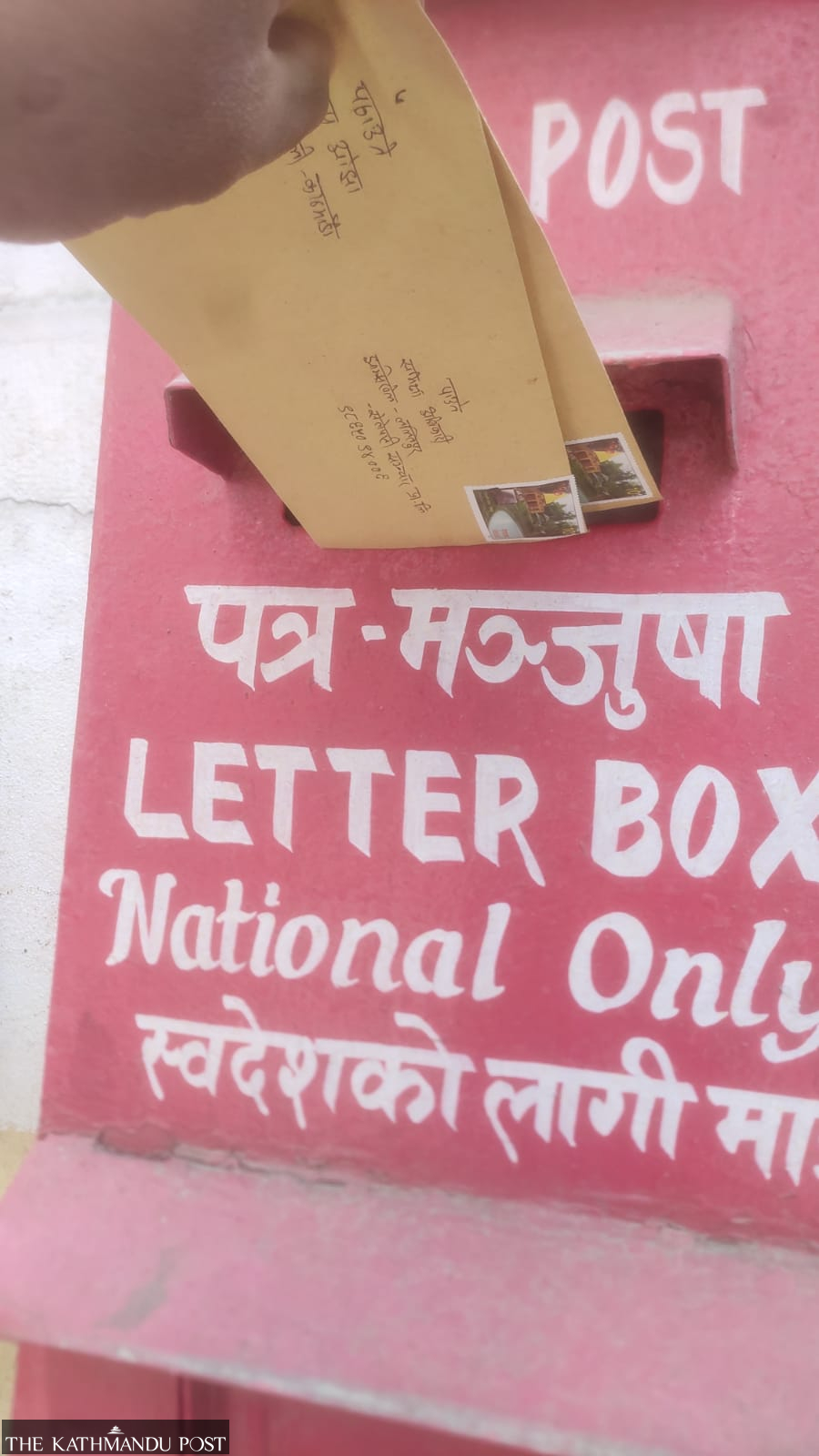

Khanal says until two decades ago, whenever post office staff opened the templed-shaped post boxes, they used to be filled with letters.

“These days I wonder if many, especially the young generation, even know what these red boxes mean,” said Khanal. “There are a handful of letters these days. Many throw noodle wrappers and other discarded stuff into these boxes. I wonder if the teenagers consider these letter boxes dustbins.”

But with the easy availability of the internet, sending letters and messages or mails became so easy—just a click away. The postal service gradually faced the threat of going the way of the dodo. People started calling the postal “snail mail” in derision.

Nepal’s postal service, however, has a history of its own. It dates back to 1878.

Initially established as “Nepal Hulak Ghar”, it used to be a pioneer government office in the country that would provide only institutional and individual letters.

Even though not many people write letters these days, it continues to provide services all across the country, mostly delivering official letters and official and individual parcels. The outbound parcel service, however, was discontinued after the pandemic began.

There are currently a total of 3,997 branches across the country.

.jpg)

According to the Postal Service Department, 17,152 staff are working across the country. Of them, 15,446 are postmen (over 90 percent). As many as 10,858 postmen work on an hourly basis (they work for two hours a day), according to Harish Chandra Joshi, an information officer at the General Post Office.

As many as 4,588 postmen are permanent staff, while the Office has only 1,706 other staff—joint secretary to peons.

Mani Ram Pokharel, an incharge of the delivery section at the General Post Office in Dilli Bazaar, says these days the task of postmen is to pass letters from banks to their clients with loan-related matters, insurance companies, government offices and courts.

According to Pokharel, altogether there are 15 area post offices and five counters where one can drop letters in Kathmandu.

“Since government offices and courts and banks and insurance companies need hard copies, our duty has been limited to delivering such letters only these days,” said Pokharel.

There used to be a time when the General Post Office, which was situated at Sundhara before the 2015 earthquakes, would see hustle and bustle, with people queuing up to post their letters. The constant thud sound used to reverberate as the staff hammered on the stamps to put the postmark to indicate their cancellation and origin and date and time of mailing.

On a recent afternoon when the Post visited the General Post Office at its new location in Dilli Bazaar, it was quiet with only a handful of staff, including Khatri and Khanal, shooting the breeze.

“No one writes personal letters these days and why would they?” said Yagya Raj Bhatta, director at the Postal Service Department. “There is no need as such, as people can just send a message or mail via mobile phone and they can even do a video chat whenever they want.”

With the number of letters drastically down, the General Post Office’s revenue, which mostly used to come from selling stamps, too has gone down. Officials say the office is actually running at a loss.

.jpg)

According to data from the Philatelic and Postal Management Office under the Postal Service Department, in the fiscal year 2016-17, it generated Rs 300 million, while in the fiscal year 2017-18, the revenue stood at Rs440 million.

In 2018-19 and in the subsequent year, it earned Rs340 million each. Similarly in 2020-2021, it earned just Rs260 million, which again went down in 2021-22 to Rs200 million.

Yagya Raj Bhatta, director of the Postal Service Department, said the government allocates Rs3 billion annually to the Office, which covers their administrative and other costs, including salary.

“Ours is a public service office; there is no issue of profit or loss,” said Bhatta. “It’s incumbent upon the government to pay for the post office’s staff salary.”

According to Shalikram Nepal, a section officer at Philatelic and Postal Management Office who retired two weeks ago after serving for 36 years, this fiscal year a total of 17 million stamps were printed for which 25 million was spent.

“Two decades ago also, stamps in the same number used to be printed and the earning used to stand at Rs100 million. This amount used to be big during those days,” said Nepal. “But not anymore. Stamp sales have also gone down.”

Since members of the public have stopped writing letters, the only time they use the postage stamps is when they visit some government offices or fill insurance forms because an archaic law introduced six decades ago says so.

“The office raises a paltry amount of revenue these days, which is not enough for the upkeep of the offices across the country and paying salary to postmen and staff,” said Nepal.

Kalpana Shrestha, chief of the General Post Office, said even if there are no personal letters to deliver these days, whatever task the Office has to perform—like delivering official letters and parcels—it has been doing efficiently.

“We have four vans to distribute letters and we also have 34 postmen in our delivery section, so within the Valley, if the post office receives letters before 12pm, they are delivered the same day,” said Shrestha. “If letters are posted after 12pm, they are delivered within the Valley the next day.”

Footnote: The Post on March 10 dropped two letters in a post box at the General Post Office in Dilli Bazaar addressed to its office in Thapathali. The letters have not arrived yet.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu.jpg)