National

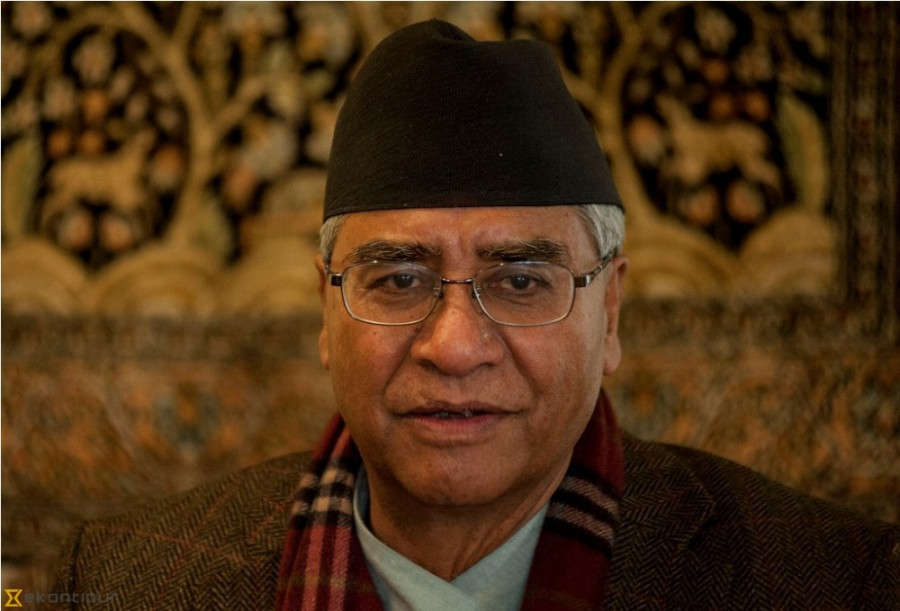

Deuba’s fifth term: Six weeks go by with 17 ministries still under him

The prime minister has not been able to expand his Cabinet even in more than 40 days, and observers say a lack of dedicated ministers hugely affects governance.

Tika R Pradhan

In the last week of June, about a month after then KP Sharma Oli government dissolved the House of Representatives, the Supreme Court annulled appointments of 20 ministers—17 Cabinet ministers and three ministers of state.

They were appointed by Oli in two phases–on June 4 and June 10. Oli’s Council of Ministers was reduced to five members after the order. Since the Supreme Court had said a Cabinet expansion was against the spirit of the constitution, the decision came as a big blow to Oli, but there were concerns about an incomplete Council of Ministers in the midst of a pandemic. There were concerns about governance, as Oli was already facing criticism for poor delivery as prime minister.

About three weeks later, the Supreme Court defenestrated Oli and installed Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba in his place. Deuba took the oath of office as prime minister on July 13 and formed a five-member Cabinet. Later on July 25, he appointed Umesh Shrestha as the state minister for health, inviting a fair share of criticism.

It has been six weeks since Deuba took over the reins and he is still running the government with the same four ministers and one state minister. Deuba himself is leading 17 ministries.

Rameshwor Khanal, a former finance secretary, says not having dedicated ministers adversely affects overall governance and that a complete government becomes even more necessary when the country is facing a crisis, like the Covid-19 pandemic.

“There are various proposals which are of importance with respect to the nation and the public and they need urgent addressal. And we need ministers to take such proposals to the Cabinet,” said Khanal. “Some decisions can be taken by the secretaries, but usually bureaucrats refrain from doing so for various reasons, including retribution.”

When Deuba took charge, it was apparent that he had a little over one year to lead the government. He was well aware that he had just a handful of jobs to accomplish—acquiring vaccines and vaccinating as many people against Covid-19, fixing relations with neighbours and other countries, bringing the constitutional process and the parliamentary system back on track, and ultimately conducting elections in a free and fair manner.

Despite being one of the first countries in the world to launch the vaccination drive, Nepal’s inoculation campaign has faltered due to its failure to secure enough doses.

After a second wave of Covid-19 hit the country hard, cases gradually declined, but the country is not out of the woods yet and experts have warned of a third wave. With the start of the festival season, the risk has further increased.

Experts have suggested scaling up vaccination.

As of Sunday, a little over 16 percent of the 30 million people have taken their first dose of vaccine and a little over 12.82 percent have been fully vaccinated.

Nepal so far has received 13,227,590 doses of Covid-19 vaccines from various sources, a big chunk of them in grants.

Observers say Deuba should have immediately appointed dedicated ministers at least at health and foreign ministries, two agencies that can play crucial roles in exploring options to secure vaccine doses. As Oli had left Nepal’s relations with neighbours in a state of confusion, Deuba should have paid attention to the appointment of foreign minister, according to them.

After the Taliban took control of Kabul at lightning speed, the South Asian region is set to see a geopolitical flux and Nepal cannot remain untouched by the impact. The immediate focus is on evacuating Nepalis stranded in Afghanistan. Deuba does not have a foreign minister—he himself is leading the ministry. To carry out that work, he has set up a committee of bureaucrats.

“It’s the very nature of a coalition government,” said Umesh Mainali, former home secretary and chairman of the Public Service Commission. “A prime minister leading a coalition government often faces challenges when it comes to Cabinet expansion, as there are too many aspirants from supporting parties.”

But, according to Mainali, governance should not be hit.

“Without dedicated ministers, only regular and day-to-day tasks can be performed. In extraordinary times, like at present when the country is facing a Covid-19 crisis, it would be better for the prime minister to give his government its full shape at the earliest,” said Mainali.

Deuba is not likely to expand his Cabinet at least until Wednesday, the day the Election Commission is scheduled to examine the documents presented by the Madhav Nepal group of the CPN-UML to register a new party—CPN (Unified Socialist). The Nepal group of the UML had played a crucial role in installing Deuba as prime minister. Once the party is registered, Deuba is likely to give some ministerial berths to the Nepal faction.

Then there are the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) and the Janata Samajbadi Party (JSP) led by Upendra Yadav and Baburam Bhattarai. Deuba needs to satisfy them as well. But the bigger challenge is managing his own party, as in Deuba’s Nepali Congress also, there are factions with many aspirants for ministerial positions.

Observers and former bureaucrats say given Nepal’s lethargic bureaucracy and politicians’ tendency to be vindictive, having ministers at all ministries is key to ensuring effective governance.

“By nature, our bureaucracy is not very proactive. A lack of ministers makes officials even more lethargic,” said Kedar Bahadur Adhikari, a former secretary.

“So not having ministers definitely affects governance.”

When Deuba was appointed prime minister through a court decree last month, observers were quick to say that he did not inspire hope, as he had already been tried and tested four times before.

Deuba himself had a chance to recoup his image on the heels of Oli’s misadventures that threatened the constitutional system and democratic processes. He, however, is now receiving criticism for doing exactly what the Oli government had been doing. The ordinance to break a political party, issued a day after proroguing the House, is just an example.

With Parliament prorogued, and over a dozen ministries concentrated under Deuba, observers fear anomalies and corruption.

According to Khem Raj Regmi, former president of Transparency International Nepal, in the absence of dedicated ministers, there are chances people close to the prime minister could try to take undue advantage, giving rise to corruption.

“For those with malafide intentions, absence of ministers at various ministries can be a good opportunity to exploit the situation,” said Regmi, also a former secretary.

23.02°C Kathmandu

23.02°C Kathmandu