National

Transitional justice bodies get new term but conflict victims have little hope

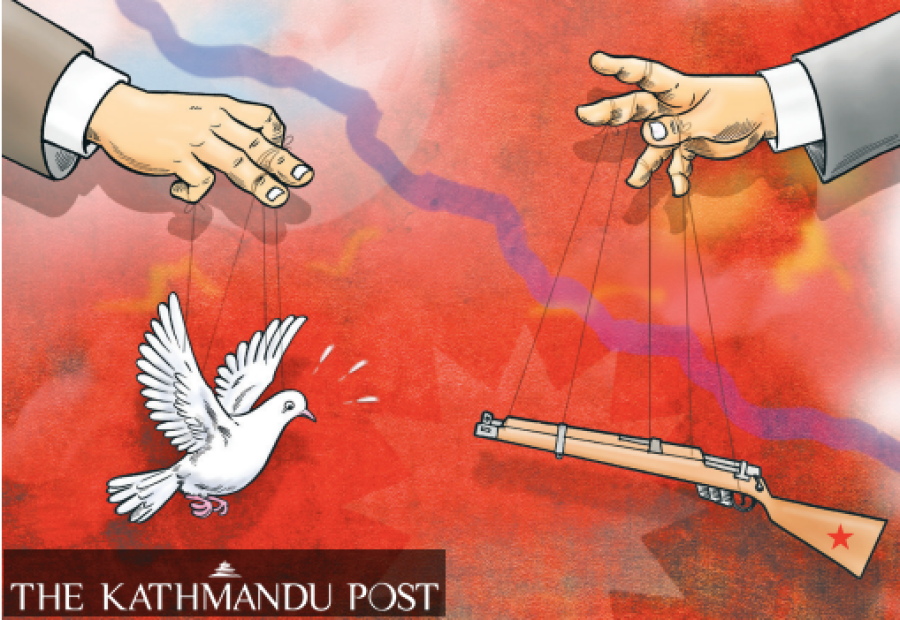

Rights activists say the Congress and Maoist Centre have got another chance to complete the peace deal by settling insurgency-era issues, but progress remains dismal.

Binod Ghimire

In one of the first orders of business, the incoming Sher Bahadur Deuba government has extended the terms of two transitional justice commissions and their office-bearers by a year.

“The extension of the terms was necessary as the commissions haven’t completed their task,” Uday Sapkota, secretary at the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, told the Post. “The Cabinet made the decision for the extension of one year.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons were formed in 2015 as mandated by the Enforced Disappearance Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Act, 2014 to look into gross human rights violations during the decade-long Maoist conflict that ended in 2006.

Although it has been six years since they were formed and two sets of office-bearers have served in them, the progress so far has been negligible.

Human rights activists say that it would be fitting if cases related to the armed conflict, in which some 13,000 lost their lives, were resolved when the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) were in power.

“It is the responsibility of the Congress and the Maoist Centre to conclude the transitional justice process because first, they were the warring parties and second, it was then Nepali Congress president and prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala and Maoist Chairman Dahal who signed the Comprehensive Peace Accord in 2006,” said Charan Prasain, a human rights activist. “The then revolutionary Maoists joined the mainstream politics giving up arms following the deal.”

When the Maoists were fighting against the state, the Nepali Congress was in power most of the time.

But victims are not hopeful that the remaining task of the peace deal will be completed anytime soon as the Nepali Congress-Maoist Centre alliance was in the government in 2017 too.

“Deuba and Dahal, the Maoist chair, are the major perpetrators who fought against each other at some point,” Ram Bhandari, a conflict victim activist, told the Post. “What would you expect when major perpetrators are together in the government?”

Bhandari’s father was arrested by Nepal Police in December 2001 never to be found again.

The highest number of cases of disappearance were registered when Deuba was the prime minister. The government led by Deuba had imposed an emergency on November 26, 2001.

Human rights activists say extending the terms of the two commissions without amending the Act as per the Supreme Court verdict is meaningless. The Supreme Court in 2015 directed the government to remove the provisions related to blanket amnesty for those involved in gross human rights violations like torture, rape, and murder.

However, successive governments have been reluctant to implement the court order. Sushil Koirala of Nepali Congress led the government when the Supreme Court issued the ruling. Five governments of all three major parties—CPN-UML, the Congress and the Maoist Centre—have been formed since. However, no government took a serious initiative for the amendment.

“We don’t have trust in the commissions unless the new sets of office-bearers are appointed through a transparent process and the Act is amended in line with the court ruling,” Kapil Shrestha, a former member of the National Human Rights Commission, told the Post. “However, no government and parties are serious about it.”

The two commissions do not have much to show in terms of progress they have made.

This is the fourth time the government extended the tenure of the transitional justice commissions formed six and a half years back. They originally had a two-year mandate to complete investigations into the conflict-era cases of human rights violations and ascertain the whereabouts of hundreds of people who disappeared during the insurgency.

However, the commissions couldn’t even collect the complaints during the two-year period. The government, through a revision in the Act, extended their terms by another two years. In its four years of tenure, the previous truth commission led by Surya Kiran Gurung received 63,718 complaints while it hardly completed preliminary investigation of around 3,800 complaints. Similarly, the disappearance commission led by Lokendra Mallick got 3,223 complaints from family members saying their loved ones had disappeared during the conflict. Of these, the commission decided to look into 2,506 complaints saying the rest didn’t fall under its jurisdiction.

The Mallick-led commission completed the preliminary investigation which included verifying complaints from the complainants. With no progress in completing the investigation, the government in 2019 extended the terms of the commissions yet again through a revision in the Act. The government, following the widespread criticism that the commissions had failed in performing their jobs, decided to relieve the Gurung and Mallick-led teams on April 15, 2019.

New office-bearers in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons were appointed in January 2020, though the victims, human rights defenders, and national and international human rights organisations had expressed serious reservations over their appointment process.

They blamed that the chairs of commissions and members were appointed on the basis of quotas for the political parties rather than adopting a transparent procedure.

Ganesh Dutta Bhatta became the chair of the truth commission from the Nepali Congress quota while Yubraj Subedi was picked as the chair of the disappearance commission on the then Nepal Communist Party (NCP) quota.

When their one-year terms were completed the KP Sharma Oli government in February amended the Enforced Disappearance Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Act, 2014 through an ordinance, giving an extension to the commissions till July 15.

On Thursday Deuba could extend the terms of the commissions and the office-bearers without an ordinance as the Act, after amendment in 2019, has a provision that says the term of the commissions would be of one year with a possibility of extension of another one year.

The Deuba government extended the term based on the clause which gives the possibility of extension by a year.

In the last year and a half, the Bhatta and Subedi-led commissions haven’t made any significant progress in investigating the complaints. The disappearance commission has completed preliminary investigations of all the complaints while the truth commission has carried out primary investigations of around 5,000 complaints.

However, they haven’t completed investigating a single case so far.

“It is evident that the present leadership is incompetent to provide justice to the victims,” Suman Adhikari, former chairperson of the Conflict Victims’ Common Platform, told the Post. “By giving them an extension, the government has shown it is least bothered about the plight of the victims”

Prasain, the human rights activist, says the Nepali Congress and the Maoist Centre should take this opportunity to finish the job they started, but the blanket extension of the terms of the two commissions was not a good way to start.

“The two parties have an opportunity to conclude the remaining task of the peace process by concluding the transitional justice process,” said Prasain, the human rights activist. “However, the way the terms of the two commissions were extended Thursday shows they aren’t interested in doing so.”

14.38°C Kathmandu

14.38°C Kathmandu