National

In two years, Oli administration’s foreign policy has been largely one-sided, say analysts

Although the visit of the Chinese president was a success, issues with India over Kalapani and the US over the MCC continue to overshadow Oli’s foreign policy.

Anil Giri

When KP Sharma Oli returned to power two years ago, on February 15, 2018, after the 2015 Indian blockade, his government made a number of promises vis-a-vis foreign policy.

The Nepal Communist Party (NCP), riding a nationalist wave in the wake of the blockade, had announced that all unequal treaties signed with India and other countries would be replaced and that Nepal’s foreign policy would be conducted on the basis of equality, mutual benefit and respect, as per the principles of Panchasheel.

The party said that relations with India and China would be strengthened and deepened while diplomatic efforts would be carried out to settle boundary disputes and manage border points, according to its election manifesto.

But for the Oli administration, the last two years have been a mixed bag, with the list of success stories too short to boast about. The party has rather plunged into a quagmire, failing to address some crucial challenges, including the reshaping of ties with India and the United States.

But the Oli administration is currently caught up in protest by members of the ruling party itself against the United States’ Millenium Challenge Corporation Nepal Compact. The ongoing controversy over the $500 million US grant may not only create diplomatic tensions with Washington but could also bring the credibility of Nepal—or the Oli administration, for that matter—into question.

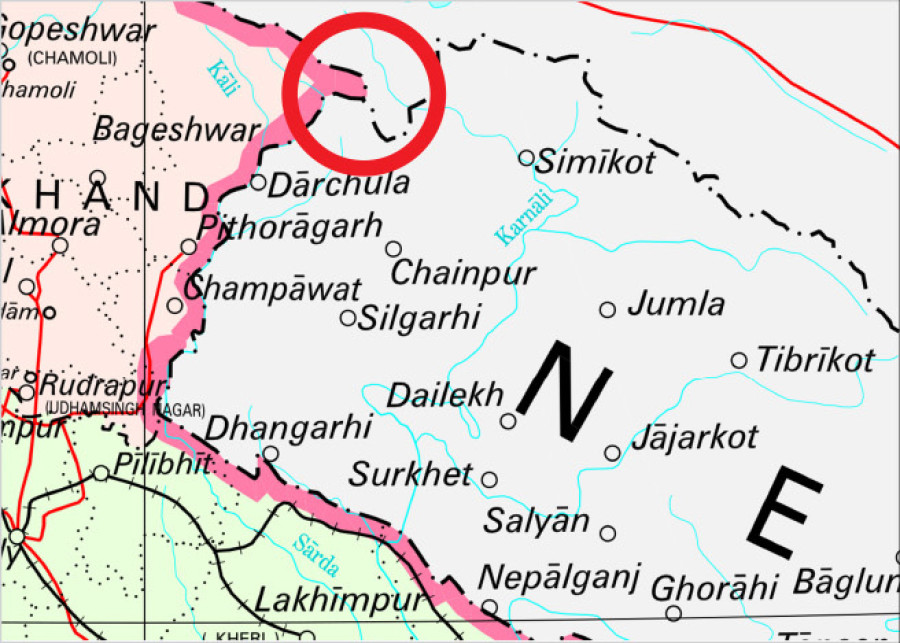

Since November last year, the Oli administration has been struggling to find a way to deal with New Delhi after India’s new political map placed Kalapani, which Nepal claims as its own, within its borders. The Oli administration has failed even to extract a date to sit for talks with Delhi.

There has also been no tangible progress on the report of the Eminent Persons’ Group on Nepal-India relations.

Foreign policy analysts say that the Oli government was already struggling to redefine its foreign policy, and the MCC has emerged as its biggest challenge.

“The MCC row exposed the biggest fault line in Nepali diplomacy,” said Nishchal Nath Pandey, director of the Centre for South Asian Studies, a foreign policy think tank based in Kathmandu. “Let alone national consensus among political parties, the ruling party itself appears to be sharply divided over the US programme. This could be due to a diplomatic failure on the Oli government’s part.”

A number of public statements by ruling party leaders have also put the Oli government in a fix. Most tellingly, in January last year, party co-chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal’s statement criticising “US interference in Venezuela’s internal matters” created a diplomatic kerfuffle with Washington.

The Oli government’s move of hosting the Asia Pacific Summit, an event sponsored by a controversial South Korea-based non-government organisation, the Universal Peace Foundation, had also met with a lot of criticism.

Party leaders and experts say that the Oli government has appeared directionless with no concrete plan when it comes to reshaping the country’s foreign policy, which for years has been at the mercy of a few political leaders.

Narayan Khadka, the shadow foreign minister from the opposition Nepali Congress, said the Oli government’s foreign policy has been rather lopsided.

“There are growing concerns about the government tilting towards China,” Khadka told the Post. “This shows that the Oli government has failed to conduct a balanced foreign policy.”

Oli’s tilt towards the north started since his first stint in office, during the 2015 border blockade. As imports slowed to a crawl, creating a shortage of daily essentials, Oli in 2016 signed a slew of deals with Beijing in a bid to diversify trade and pave the way for third-country trade via China.

After returning to power in 2018, the Oli government continued its effort to deepen ties with China, which foreign policy experts describe as a positive move.

Oli received applause from across the political spectrum for making Chinese President Xi Jinping’ visit to Nepal in October last year possible.

But there have been no high-level visits from other countries, which also reflects the lopsided diplomacy of the Oli government, according to Khadka.

“With India, the Oli administration has failed to settle the boundary row,” said Khadka. “Party leaders and ministers in the Oli government are divided over the MCC. This could again be the result of a one-sided foreign policy.”

Ruling party leaders, though, say that Nepal’s foreign policy and international relations might have had some hiccups but there has been an improvement on the whole. They also dismissed allegations that the Oli government’s foreign policy is one-sided.

“Our relations with India and China are advancing and relations with major powers and key international organisations have become stronger,” said Bishnu Rijal, deputy head of the ruling party’s international department. “As far as some boundary issues are concerned, they have been there for quite some time. But the government was quick to respond when the Kalapani issue surfaced.”

Rijal described Sagarmatha Sambad, scheduled for April 2-4, as a good initiative to strengthen Nepal’s foreign policy.

Pandey too commended the plan to convene the Sagarmatha Sambad.

“But ambassadors abroad need to a play constructive role to make it successful, which could largely help Nepal strengthen its foreign policy,” said Pandey.

8.22°C Kathmandu

8.22°C Kathmandu