National

“I thought I would die”

Despite laws on domestic violence, archaic and insensitive treatment by police and the justice system force women in Nepal to remain trapped in cycles of abuse, even when they muster the courage to report them.

Bhrikuti Rai

The beating was so brutal that Vibha Rana was left with deep cuts above her left eye that needed multiple stitches. Her face was dripping with blood and she couldn’t see clearly as her vision was blurred by the beating. All she felt was a throbbing pain in her head.

This wasn’t the first time her husband’s merciless thrashing had landed her in the hospital. In their nearly 40 years of marriage, they had frequented couples counselling but she was also a regular at numerous emergency rooms and operation theatres, sometimes battered by her husband’s rage and other times, by her adult son’s. In the past, she would’ve gone back home, cried alone in a dark room. The next day, she would wake up and slip back into everyday life, hiding the pain under a big, bright smile and the bruises underneath layers of makeup—only to be beaten again.

But after what happened on a frigid December night in 2018, something changed. After the doctors at Norvic Hospital treated her wounds, instead of going back to her home in Babarmahal, she went to a relative’s place. She cleaned herself up, drank a cup of coffee, lay down in bed, and decided that it would be the last time her husband would ever beat her.

“I thought I would die if I didn’t escape that torture chamber,” she said. “It was brutal. He beat me to a pulp, he could’ve killed me, and that night I realised my life is the most precious thing to me.”

Vibha, who runs one of the oldest Montessori schools in Kathmandu, doesn’t exactly remember when the beatings started, because they happened so regularly and so many times. But in a series of interviews with The Kathmandu Post, the 61-year-old recounted in vivid detail the intensity of those beatings, which left her with deep scars and countless broken bones.

“There were beatings and then there were severe beatings,” she said.

It was one such severe beating in December that prompted her to file a domestic violence case, which is currently being heard at the Kathmandu District Court.

According to court documents, her husband, Saurya Rana—who heads several companies that deal in everything from automobiles to energy and is also the president of the Nepal-India Chamber of Commerce and Industry—had been violently assaulting her for decades, and had made it dangerous for her to live in the same house with him. In the documents, filed as a separate case in 2016, Vibha also alleges that her husband has not provided her with any financial support as maintenance, and also prevented her from taking her belongings with her when she was forced out of the house.

In an interview with the Post, Saurya Rana said he could not comment on questions related to domestic violence because the case is sub judice in the district court. He pushed back on Vibha’s claims about financial support, saying she hasn’t initiated the court procedures which would have let him give her the money.

But in the past, Saurya has vehemently denied the allegations against him. In a police testimony given after Vibha filed a domestic violence case in December 2018, Saurya says he “hasn’t subjected Vibha to any kind of domestic violence and that she has in fact lodged the case just to torment me”. He goes on to say how it was Vibha, “who always did as she pleased and used foul language during heated exchanges, which she used to incite”.

Countering the allegations of physical violence on the night of December 1, which left Vibha with deep injuries requiring multiple stitches, he told the police, “Vibha slipped and hit her head on a dustbin when she was trying to run away with my mother’s precious jewellery.”

According to Vibha, her husband, who is one of the most powerful men in Kathmandu, comes across as a “suave and cultured gentleman”. But that mask comes off when he loses his temper, she says.

“I stayed on for all these years for the sake of my children’s future and also because I was conditioned to think that violence was okay and I had to tolerate it for the family’s honour,” she said.

Vibha’s plight is not uncommon. Despite having laws on domestic violence, many women in Nepal are trapped in cycles of abuse for decades. According to the National Demographic Health Survey 2016, 22 percent of Nepali women between the ages of 15 and 49 years have experienced physical violence of some kind, with a prevalence of six percent among unmarried women and 25 percent among married women. The survey also found that 66 percent of women who have experienced any type of physical or sexual violence have not sought any help or talked to anyone about resisting or stopping the violence.

[Read: Calls to national helpline for women are growing, but it’s accessible to only a few]

Women’s rights advocates and lawyers say that most women aren’t fully aware of what legal action they can take against their perpetrators. And even when they do, factors like financial dependency on the husband, social stigma attached to reporting domestic violence, and clinging on to marriage for the sake of “prestige” prevent women from reporting these cases.

“Not everyone has the courage to speak up,” said lawyer Anita Thapaliya of Legal Aid and Consultancy Centre, which provides free legal aid to women and children who’ve suffered from gender-based violence.

And even when they do, the incentive to keep the fight up isn’t much. The service centres for women battered by domestic violence aren’t effective or adequate. Government’s legal aid doesn’t reach everyone and this prevents victims of domestic violence from taking their cases to the police and the courts in the first place, Thapaliya says. Furthermore, the treatment that most women are subjected to at police stations and later in the courts is archaic, insensitive and wears out their patience, according to a National Human Rights Council report.

“How many people are they going to tell the same story, and how long will they be able to afford the exorbitant legal fees when their cases drag on for years?” said Thapaliya. “They would rather hide their pain for the sake of prestige before society than bring it out in the open.”

When the case reaches the courts, women don’t always get compensated fairly and in many cases, the perpetrator gets acquitted for a lack of evidence. And if a powerful man, like in the case of the Ranas, is being alleged of violence and assault, getting the legal process started itself can become challenging.

“Former Speaker Krishna Bahadur Mahara’s case is a glaring example of how difficult it is to even arrest the alleged perpetrator when he is a powerful person,” said Thapaliya. Earlier in October, a junior staff at the Parliament Secretariat accused Mahara of raping her. It took several days and mounting social media pressure for the authorities to arrest Mahara and file a chargesheet.

A sub-inspector at a women’s cell in Lalitpur, who spoke on condition of anonymity because she was not authorised to speak to the press, said that the pressure from “higher-ups” in domestic violence cases, when the perpetrator has access to the corridors of power, affects their investigations.

“We get calls from higher-ups saying so and so needs to be ‘looked after properly’ even before the perpetrator comes to the police station,” the officer told The Post. “So sometimes we cannot even give victims the time and effort required during the investigation.”

For Vibha too, her husband’s powerful connections intimidated her, and they still do, she says, when it comes to asking for help and expecting to be supported. But the fear and hesitation to report domestic violence aren’t just limited to women married to well-connected, powerful men. According to social workers, advocates and police officers in women’s cells, the fear of backlash after reporting domestic violence permeates all social classes.

In the seven years of her marriage, Lhasang Lama was choked, kicked and punched countless times by her husband Sangey Bahadur Ghising, who worked as a daily wage labourer in Kathmandu. The beatings were so violent that she often passed out while her infant daughter wailed next to her. The beating landed her in hospital, but reporting the violence never occurred to her. Not even when Ghising tried to kill her with a khukuri. A lack of support from her family and her financial dependence on her husband to raise her young daughter were the primary reasons preventing her from filing a domestic violence case for years. When she finally did go to the Dhulikhel police station about two years ago, after the beatings and choking had left her with severe chest pain, the police and her family insisted they reconcile.

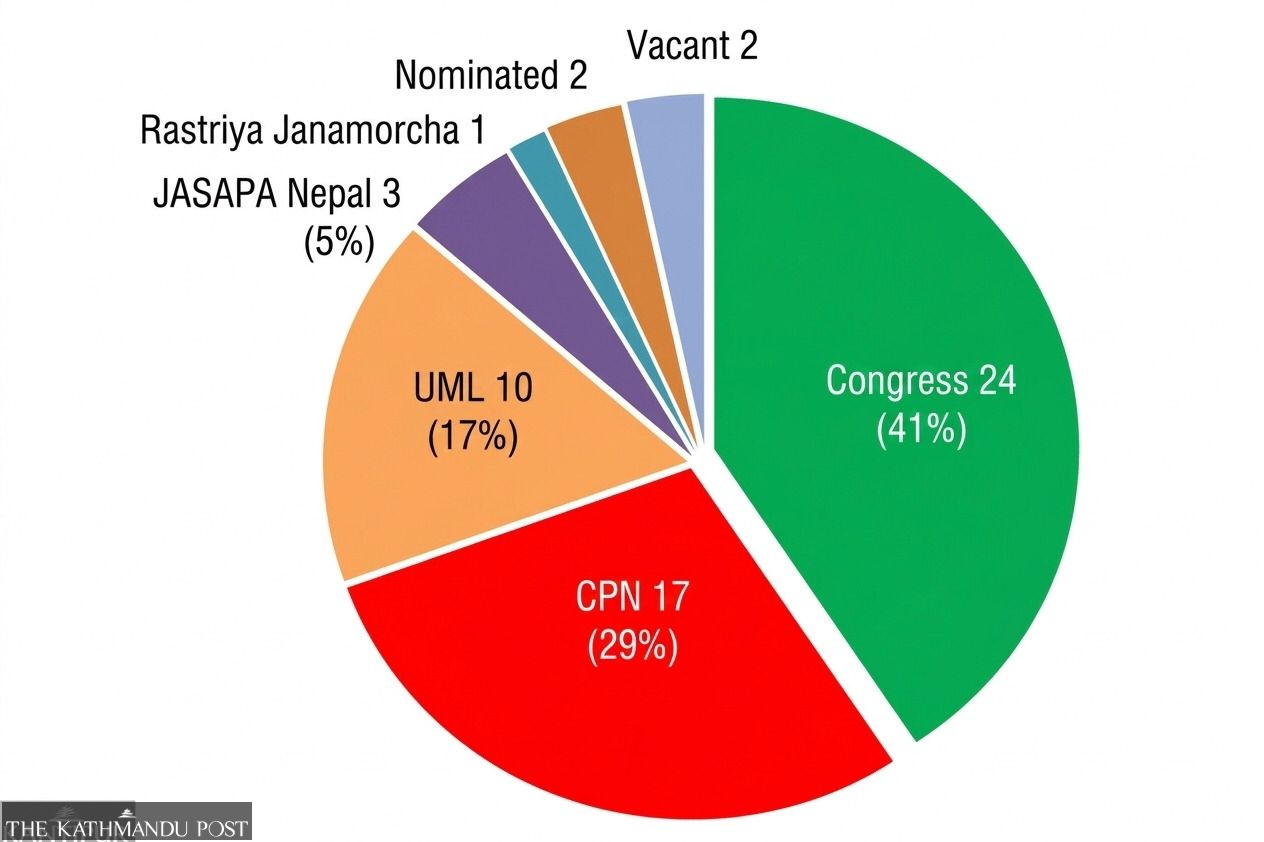

According to the Nepal Police, the number of reported domestic violence cases has increased exponentially in the last seven years, from 1,800 in 2012 to nearly 15,000 in 2018. In the majority of these cases, the police push for reconciliation and only a fraction reach the courts.

“At the police station, he [Ghising] admitted he wanted to kill me before apologising and promising that he wouldn’t treat me that way again,” said Lama. “I didn’t want to go back with him, but my own family said he was a good man at the end of the day, and that I should make amends with him.”

So she did. But after two months, the kicks and punches resumed, leaving her body black and blue.

“It takes an immense amount of courage and counselling to even come to the decision to report domestic violence,” said Sapana Shrestha of Saathi, an organisation that runs a shelter home for women and girls who’ve faced physical and sexual violence. “Women are expected to be tolerant of slaps and kicks, which they are conditioned to think of as normal in relationships, and this mindset has to change.”

For Lama, that mindset began changing late last year, when her husband’s rage and beatings started to seriously affect her health.

“I couldn’t breathe properly because of the chest pains and limped for several days after he thrashed me for something I don’t even remember now,” she said. “I went to the hospital to get checked and said I cannot live like this anymore.”

Lama called up her relatives, who took her to Kalimati police station and then to the National Women Commission. When she told them she had nowhere to go and couldn’t go back living with her husband, she was sent to Saathi’s shelter home in Lalitpur. During her two-month stay there, she received counselling and also a job at a hostel, after which she filed a case against her husband at the Kathmandu District Court with the help of Saathi. Now she wants to complete her school education and has started taking private classes in the morning before going to her job at a clothing store in Baneshwor.

Although Lama says she doesn’t regret her decision to leave her husband, she is still worried about her daughter, who now lives with his relatives. Ghising doesn’t always let her meet their six-year-old daughter, leaving her distressed about what kind of relationship she will have later on with her only child. Despite losing so much in the past year, she says she isn’t sure if justice will be delivered soon.

“I go to the court whenever I get called, but there is no one to speak on my behalf,” she said. “I don’t know how long it will take before the divorce is finalised and he gets punished for what he did to me for all these years.”

Had the justice process moved swiftly, women like Lama would have more confidence in the system and could move on with their lives, says Renu Shah, a psychologist at CASANepal, a shelter for women survivors of gender-based violence. Dilly-dallying by the police in their investigations and lengthy legal procedures are a major source of anxiety and frustration for the women who come to the shelter, says Shah. As a result, women aren’t able to focus on other things like training or counselling when they know the authorities haven’t started investigations.

“The inaction persists for months, especially if the woman seeking justice is from a less privileged background,” she said. “It’s all about power these days.”

The long legal battle is something Vibha also gets anxious about every day. She has been reading everything she can about the new criminal code. But since filing the case last year, she says there has only been one proper hearing. And the longer the case drags on, it’s not just peace of mind she is losing, the legal fees are also starting to add up.

“It is laborious, time-consuming and expensive,” Vibha said about the ongoing court case. She says it makes her furious just thinking about how people can get away in these cases and what happens to women who don’t have the resources to continue their legal battles.

“I have been pushed to the wall and I’m forced to live on loans,” she said. “My husband and his family bully me every time, thinking they will get away with this and I am tired.”

***

If you or someone you know want to report domestic violence, call 1145. The helpline is run by the National Women Commission.

16.35°C Kathmandu

16.35°C Kathmandu