National

Nepal continues to import pesticides at an alarming rate, government’s own data shows

Nepal imported just 50 tonnes of agriculture in 1997. Today, it imports over 600 tonnes, a majority of which comes through India.

Sangam Prasain

Even as the political fallout over the KP Sharma Oli administration’s recent decisions over pesticide testing continues, the domestic use of pesticides in Nepal’s own farm produce has been quietly growing to alarming levels.

Nepal imported 635 tonnes of pest-killing chemicals, worth around Rs830 million, in the last fiscal year alone, according to data from the Plant Quarantine and Pesticides Management Centre. Most of these pesticides—85 percent—was applied to vegetables, according to Ram Krishna Subedi, information officer at the centre.

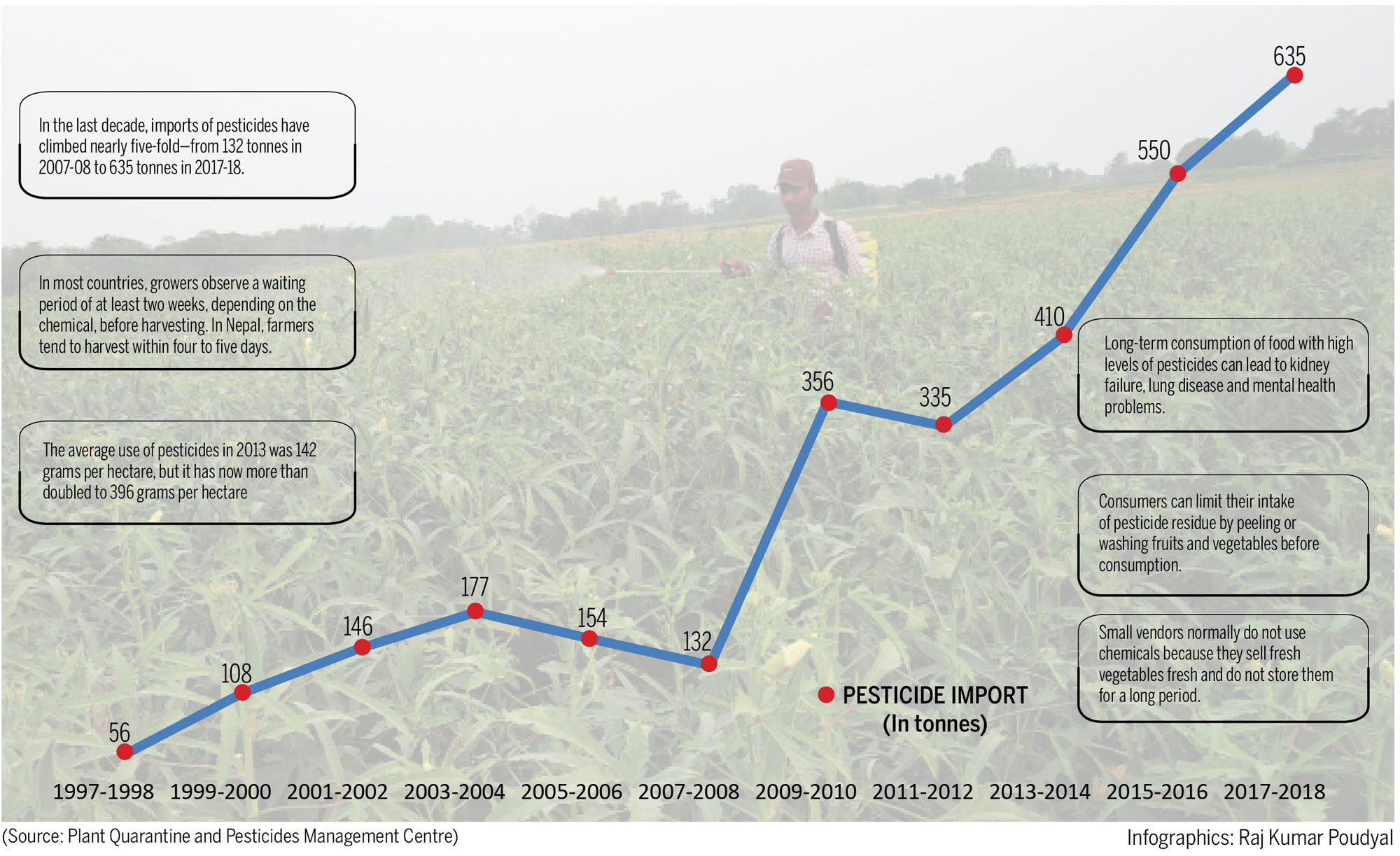

In the last decade, imports of pesticides have climbed nearly five-fold—from 132 tonnes in 2007-08 to 635 tonnes in 2017-18. Nepal started using pesticides in 1952, when USAID introduced Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, to control malaria. Pesticide imports amounted to just 50 tonnes in 1997.

“The most striking thing is that Nepal is among those countries using the least amount of pesticides, but the impact [on health] of these pesticides is among the highest in the world,” said Subedi.

Pesticides are primarily applied to produce off-season vegetables, which are expensive but are prone to insects. But as most Nepali farmers do not follow instructions before applying pesticides, their impact on the health of consumers can be much higher than in other countries where more pesticides are used, but under strict guidelines.

In most countries, growers observe a waiting period of at least two weeks, depending on the chemical, before harvesting. In Nepal, farmers tend to harvest within four to five days, which leaves lingering traces of pesticides on produce.

“As growers are in a hurry to sell their produce, they do not wait or abide by the waiting period. As a result, pesticide residue remains on crops, which can cause serious health hazards,” said Subedi.

Recently, the Oli administration’s decision to first conduct pesticide residue tests on all farm produce imports from India, and then, a swift reversal upon pressure from India has led to mounting criticism.

But fruits and vegetables grown in Nepal itself have often displayed alarming levels of pesticide residue.

In 2014, the government had set up a Rapid Pesticide Residue Analysis Laboratory at the Kalimati market, the largest wholesale market in the Kathmandu Valley. Fifty-one out of the 1,619 vegetable samples tested between 2014 and 2015 were found to contain chemicals beyond safe levels. Thirty lots of vegetables were destroyed after they proved unfit for consumption.

This strict monitoring has led farmers to apply fewer amounts of pesticides. In 2016, only eight out of the 1,936 samples tested were found to contain harmful levels of chemicals.

According to Subedi, increasing internet access has also contributed to the growing use of chemicals. When confronted with a disease or pests, many farmers search for remedies online, which often recommend the use of pesticides, he said.

While the amount of import of pesticides might be concerning, the number could be much higher, if illegal imports from across the porous border with India are taken into account, officials say.

The average use of pesticides in 2013 was 142 grams per hectare, but it has now more than doubled to 396 grams per hectare, said Rajiv Das Rajbhandari, senior plant protection officer at the Central Agricultural Laboratory.

“On vegetables, the use of pesticides is 1,600 grams per hectare due to the growth of commercial farms,” said Rajbhandari. “These farms sell off-season crops, which fetches good rates in the market.”

But compared to other countries, the use of pesticides in Nepal is lower. In India, average use is 481 grams per hectare while countries like Japan, South Korea and Italy use 11 to 16 kilograms per hectare, according to a report from the Plant Quarantine and Pesticides Management Centre.

“Despite being the world's largest users of pesticides, the impact on health in developed countries is lower because there are proper regulations and they abide by the waiting period before crops are harvested,” said Rajbhandari.

Chemical pesticide use is also much higher in the districts surrounding the Kathmandu Valley, as commercial vegetable farms rush to meet demands from the Capital. Over 45 percent of all pesticide imports are primarily employed in Kavrepalanchok, Dhading and Nuwakot.

According to World Health Organization, pesticides can be toxic to humans and can have both acute and chronic health effects, depending on the quantity and the ways in which a person is exposed.

The most at-risk population consists of people who are directly exposed to pesticides—agricultural workers who apply pesticides and others in the immediate area during and right after the pesticides are applied. The general population—those who are not in the immediate area—is exposed to significantly lower levels of pesticide residue through food and water.

But pesticide residue can also cause harmful effects on health, such as nausea, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, dizziness and anxiety, said Dr Mukti Ram Shrestha, president of the Nepal Medical Association.

“Long-term consumption of food with high levels of pesticides can lead to kidney failure, lung disease and mental health problems. They can even cause cancer and harm the foetus in pregnant women,” said Shrestha.

The Nepal Medical Association, on Tuesday, issued a press statement drawing the government’s attention to seriously take into account public health after the decision to withdraw pesticide residue tests for agriculture produce imported from India.

Consumers can limit their intake of pesticide residue by peeling or washing fruits and vegetables before consumption, according to the WHO. This can also reduce other food-borne hazards, such as harmful bacteria.

Purchasing vegetables from small vendors, rather than supermarkets, is another alternative as small vendors normally do not use chemicals since they sell fresh vegetables fresh and do not store them, according to the Plant Quarantine and Pesticides Management Centre.

Pesticides can prevent crop losses and will continue to play a role in agriculture, but their use, both to feed local populations and for export, should comply with good agricultural practices regardless of the economic status of a country, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization.

There are currently 3,034 pesticide trade names and 169 pesticides registered in Nepal, along with 11, 777 retailers dealing in pesticides. Around 90 percent of pesticides used in Nepal are imported from India.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu