National

Catch 22

An old farmer in rural Nepal will smile if the world’s climate deal helps stabilise erratic weather patterns because he can then grow crops predictably.

Navin Singh Khadka

An old farmer in rural Nepal will smile if the world’s climate deal helps stabilise erratic weather patterns because he can then grow crops predictably. But for it to happen, countries will have to make drastic cuts in fossil fuels and that could take away his son’s job in the Middle East. This is the difficult choice today’s agrarian and remittance-dependent Nepal faces—probably even without realising it.

Already, there have been job cuts in oil producing countries as the price of the fuel continues to dip and major markets like the US have begun their own production.

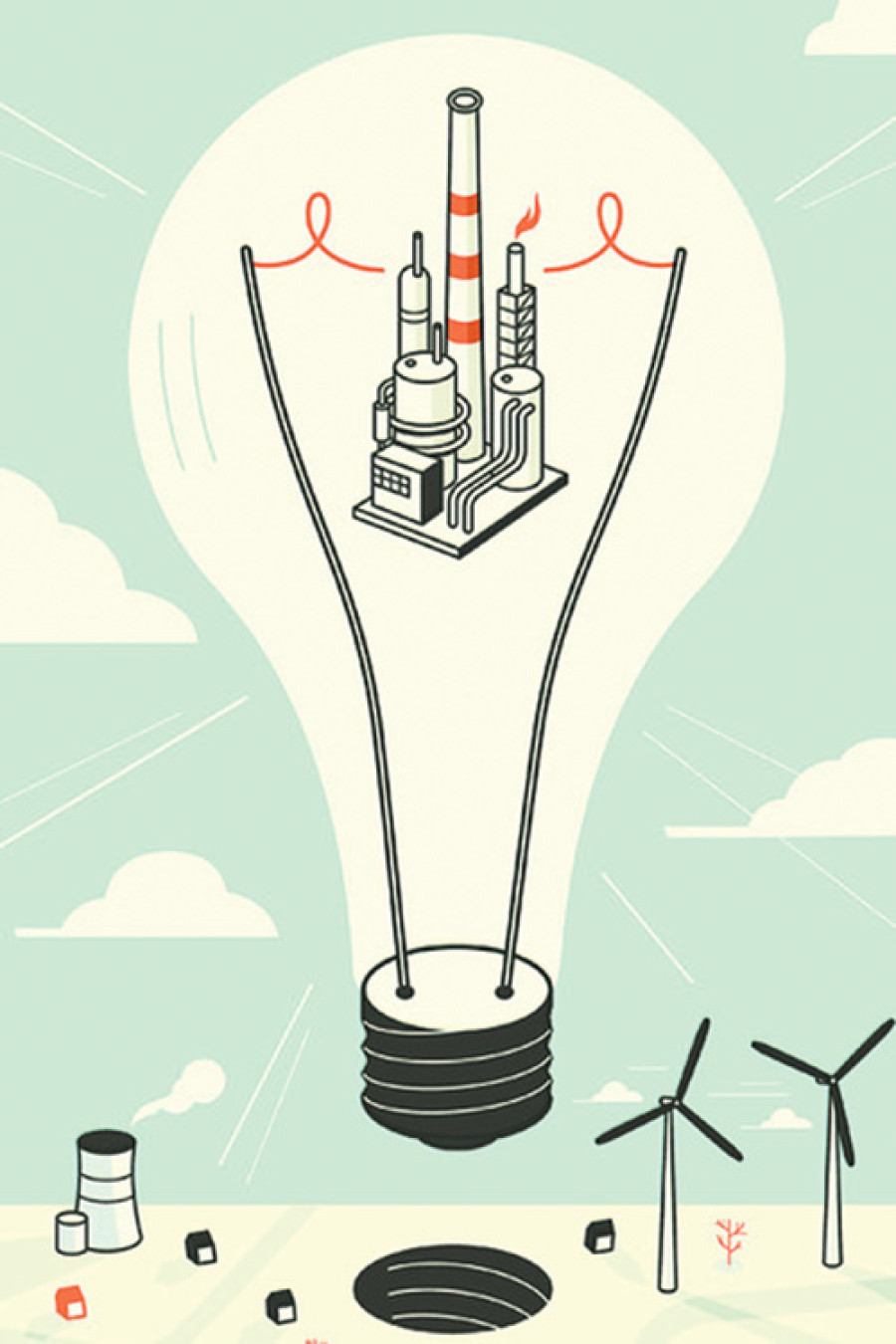

With the continued price drop in solar power technology and the wind energy market picking up, the global fossil fuel industry does have a reason to be concerned. A recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) reveals that the capacity of renewable sources, including solar, hydro and wind, to generate electricity has now overtaken that of coal.

Above all, the Paris climate agreement signed last year is unexpectedly coming into force on November 4—much earlier than it was supposed to in 2020. It aims at keeping average global temperature rise below two degree Celsius from what it was before the industrial revolution, mainly through a significant reduction in fossil fuels. Scientists say that threshold is crucial to save the world from dangerous climatic changes.

Positive developments

To be operational, the Paris accord inked last December needed ratification by a number of countries accounting for 55 percent of global greenhouse gases emissions. With 2020 as the year the clock was supposed to be on, initial expectation was that countries would take at least a couple of years to ratify the deal. But climate diplomacy saw an unprecedented flurry of action and the top three emitters—China, the US and India—submitted their instrument of ratification, as did 78 other countries. And the agreement is now all set to become international law.

Meanwhile, the world saw another significant deal on gases used in coolers and refrigerants. Hydroflurocarbons (HFCs) are nearly 20,000 times more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide, and countries in a meeting in Rwanda last month agreed to phase them out gradually. In yet another development, international civil aviation has also agreed to start cutting down its carbon emissions. This had been a hard nut to crack all these years.

Piece all these together and you will see a pattern emerging—the world by and large is indeed steadily moving towards transition to clean energy. Otherwise, that would not have been a subject of discussion between the secretary general of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. After their recent meeting, they put out a statement saying, “both secretariats acknowledged that economic diversification is an important objective for building economic resilience and agreed to explore all available capacities which can assist OPEC Member Countries in diversifying their economies and achieving just transition of work force.”

Fossil fuel vs renewables

What made it clear that the OPEC was “concerned” about the transition from fossil fuels to renewable sources was the statement: “the key role of oil in economic development and the right of developing countries to develop was stressed,” although it also added, “in this regard, the OPEC efforts towards sustainable market stability were recognized as a contribution to a healthy global economy and helping implementation of the Convention and the Paris Agreement and the transition to a low emission economy.”

There are reasons why the OPEC is already talking about the transition and wants to be prepared for it. According to the IEA’s report on renewables, they will grow 13 percent more between 2015 and 2021 than what was forecast last year, “due mostly to stronger policy backing in the United States, China, India and Mexico.” The report further added: “over the forecast period, costs are expected to drop by a quarter in solar PV and 15 percent for onshore wind.”

The study found that last year was a turning point for renewables. “Led by wind and solar, renewables represented more than half the new power capacity around the world, reaching a record 153 Gigawatt (GW), 15% more than the previous year. Most of these gains were driven by record-level wind additions of 66 GW and solar PV additions of 49 GW. About half a million solar panels were installed every day around the world last year. In China, which accounted for about half the wind additions and 40% of all renewable capacity increases, two wind turbines were installed every hour in 2015.”

While all this is happening in the world of renewable energy, the job market in fossil fuels producing countries is plummeting. “Oil and gas companies are likewise feeling the brunt, registering a 19 percent drop in demand for additional employees,” Gulf News reported last November. “Similar businesses in the UAE incurred the most significant drop in hiring, at 20 percent.” Things have not improved this year; “50,000 laid off in Saudi Arabia as oil crisis bites deeper,” said OILPRICE.com, a leading news portal on oil and energy issues, in its May report.

Concerns for Nepal

For Nepal, which earns around five billion dollars annually from its overseas workers, most of them in oil producing Middle East, all these are warning signals.

Of course, the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy is not going to be an overnight affair. Equally influential will be the result of the US presidential election. If the elected president does an about-turn from America’s commitment to the Paris climate agreement, it will send shock waves in the international climate regime. Fast emerging economies like China and India, which are also top carbon emitters, will then get a solid basis to bolster their argument that the developed countries are not doing enough and are just asking developing countries to make significant carbon cuts.

If in the meantime, the still iffy carbon capture and storage technology makes some credible scientific progress, that might prolong the life of the fossil fuel industry, although campaigns to keep the dirty energy underground are gaining ground.

Under the climate change banner, how the energy politics plays out in the long run remains to be seen. But that should not be a reason for Nepal’s policy-makers and planners to sleepwalk into a crisis. Is anyone in Parliament or the National Planning Commission listening?

Khadka is a BBC journalist based in London

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu