Money

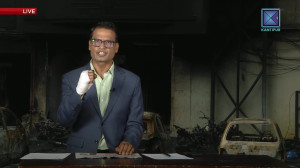

Online businesses paralysed, operators and workers

Ban on ‘unregistered’ platforms leaves small businesses, delivery services, and fundraisers stranded.

Kamalesh Thakur & Santosh Mahatara

For four years, Sanjay Kumar Chaudhary of Janakpur, an IT graduate, has been running an online business alongside his studies. He operates MM Digital Garage, which provides online services to 40 companies and employs six young people. But after the government shut down unregistered social media platforms, his work has reached a standstill.

Chaudhary, who has been engaged in online promotions and graphic design, said his business has already declined by 50 percent. “Work has stopped coming in. That’s why I’ve called only three people to the office now,” he said. “I’m losing Rs10,000 every day.”

He explained that after the government shut down Meta (formerly Facebook) and 25 other social media platforms, clients have shifted to the few operating platforms—but they are far less effective.

“The government couldn’t provide jobs for young people. And now it is taking away the few jobs we created ourselves,” he said. “This decision has only made life harder for people trying to make an honest living.”

Companies like Pathao Nepal have been hit just as hard.

Pathao launched its parcel delivery service in Janakpur ten months ago, gradually gaining ground in Dhanusha and Mahottari districts by serving around 20 customers daily. But the shutdown has brought operations to a standstill.

“Until Saturday, we were still working on earlier orders. But on Sunday, we received no new parcels at all,” said Alok Kumar Mandal, Pathao’s Janakpur branch representative. He added that once sellers lost contact with customers, delivery orders simply stopped.

Indu Singh of Janakpur is another entrepreneur whose business has collapsed.

A year ago, she switched to selling fancy goods (fashion accessories and craft items) online after rent hikes made it difficult to keep a physical shop. But her trade has been suspended for the past three days. “When you lose contact with customers, how can you do business?” she asked. “The sudden shutdown feels like the government has taken away our livelihood.”

Economist Surendra Labh argues that the government made a mistake by enforcing such measures through directives and orders instead of passing proper laws.

He warns that prolonged restrictions will damage the national economy and worsen unemployment.

“The most important thing is that without immediate alternatives, the government will lose public trust,” he said. “This move has disproportionately affected the lower classes.”

Rajat Pandey, assistant professor at Rajarshi Janak University, went further, accusing the government of gagging citizens.

He said shutting down social media without offering alternatives violated the law. “It’s not right to impose such restrictions when people have already become accustomed to the digital age,” he said. “The government is doing now what it should have done ten years ago. In the process, it is infringing on citizens’ rights.”

For many Nepalis, social media has been more than a communication tool—it has been a lifeline.

Three years ago, 19-year-old Shashidhar Panthi of ward 7 of Malika Rural Municipality in Gulmi suffered kidney failure. His family, unable to afford treatment at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital in Kathmandu, launched a fundraising campaign on Facebook. They raised Rs278,000, which helped cover crucial medical expenses.

Panthi is still undergoing treatment, which is primarily supported by that effort.

In another case, Khagishwar Pokharel of ward 2 of Madane Rural Municipality in the district broke his spine after being gored by an ox in 2020. Without money for treatment, his family despaired—until donations poured in after his story was shared on social media.

He received Rs200,000, which allowed him to undergo surgery.

Five years ago, 81-year-old Nara Bahadur BK of ward 7 of Malika Rural Municipality lost his home to a landslide. Having already lost his 23-year-old son in India, BK and his wife were left homeless. After their story spread on Facebook, well-wishers raised Rs120,000, which enabled them to rebuild.

Deepak Khatri of ward 1 of Isma Rural Municipality was a throat cancer patient who exhausted all his family’s assets on treatment in Chitwan. When the situation turned desperate, social media campaigns raised Rs200,000 for him.

Teacher Baburam Panthi of ward 2 of Isma who launched the campaign, said, “My neighbour was suffering, and social media became the bridge for help.”

Others continue to rely on online campaigns.

Megh Bahadur Kumal of ward 2 of Isma, badly injured in a fall while repairing his roof, is undergoing treatment in Butwal with the support of Rs180,000 raised via Facebook.

Even institutions have benefited.

Thanapati Basic School in ward 8 of Malika, established an endowment fund worth Rs1.07 million through social media fundraising in six months. “We spread our campaign through Facebook, and support came not only from locals but also from neighbouring districts,” said school management committee chair DB Khadka.

The fund’s interest will be used for long-term educational development, helping cover basic needs worth Rs180,000 annually.

17.62°C Kathmandu

17.62°C Kathmandu