Money

Wheat harvest likely to fall below forecast due to rain

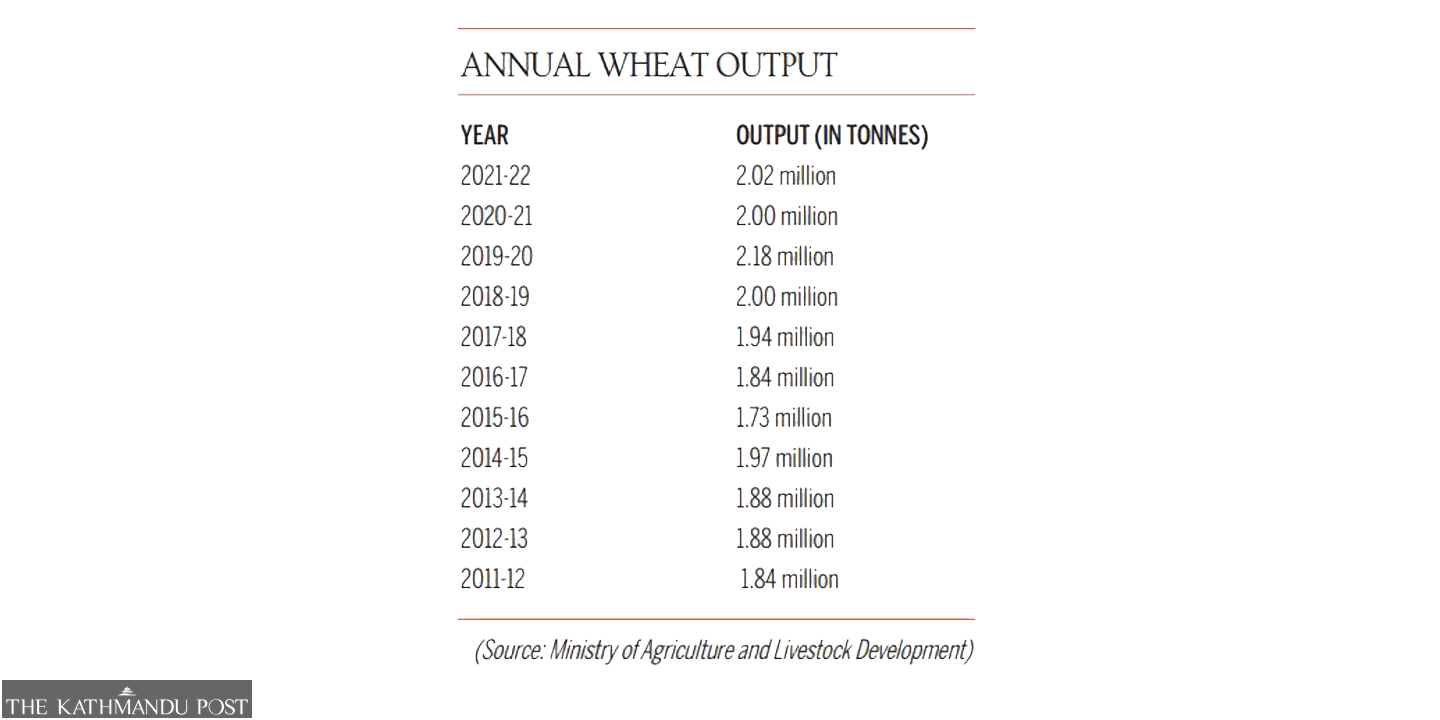

Production is likely to rise by less than 1 percent to 2.02 million tonnes, according to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development.

Sangam Prasain

Officials have predicted a lower than expected wheat harvest after the winter crop was drenched in unseasonal rains in October, which means Nepal’s battered economy could face further misfortune.

According to preliminary estimates issued by the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, the wheat harvest is likely to rise by less than 1 percent to 2.02 million tonnes.

Wheat, the country’s third largest cereal crop, is sowed in mid-November and harvested in mid-April.

"Despite abundant winter rainfall, the yield is expected to fall short of projections," said Ram Krishna Regmi, chief statistician at the ministry. "Wheat planting got underway way behind schedule this year," he said.

Heavy rainfall is unusual in Nepal during October, which is traditionally outside the monsoon season.

The rains started on October 17 last year in the western part of Nepal and then moved to the eastern part on October 19, claiming lives and damaging roads, bridges and other physical infrastructure in various districts.

The unseasonal rains and floods destroyed paddy crops worth Rs8.26 billion, the highest losses on record.

“The losses were not limited to paddy. Unusual weather patterns also severely hit the yield of winter crops, particularly wheat,” said Regmi.

The delayed paddy harvest due to rain at the maturing stage also pushed back the sowing of wheat. Shortages of fertiliser added to the farmers’ woes.

“Early sowing of wheat can lengthen the growing season and deliver increased yields. Delayed sowing will shorten the growing season, thus reducing yield potential,” said Satya Narayan Mandal, a retired soil scientist.

“Normally, grain yield declines by 1 percent with each day of delay in sowing,” said Mandal.

This year, farmers lost time clearing their fields due to wet crops. Even after the harvest, they had to wait to plant their wheat crops because of excess soil moisture and cold soil temperature.

“Many farmers were worried and sowed their wheat crops, and the impact was seen in seed germination,” said Regmi.

Farmers also faced a shortage of diammonium phosphate (DAP) fertiliser for their winter crop.

In 2021, the monsoon entered eastern Nepal two days earlier than the usual starting date of June 11 and withdrew on October 11, prolonging the rainy season by nine days and making it one of the longest wet seasons, according to the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology.

The rains again started on October 17.

The normal onset and withdrawal in eastern Nepal occur on June 13 and October 2 respectively.

Nepal witnessed a record wheat output of 1.97 million tonnes in 2014-15. Production plunged 12.1 percent to a six-year low of 1.73 million tonnes in 2015-16 due to the winter drought.

Harvests jumped 6 percent in 2016-17, reaching 1.84 million tonnes. The country’s wheat production stood at a record 1.94 million tonnes in 2017-18 despite a prolonged winter drought.

In 2018-19, output swelled to 2.08 million tonnes; and in 2019-20, the harvest reached an all-time high of 2.18 million tonnes, according to the ministry's statistics.

Last year, the drought lessened the wheat output by 8 percent to 2.00 million tonnes, according to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development.

Nepal’s official number cruncher—the Central Bureau of Statistics—has projected an economic growth rate of 5.8 percent for this fiscal year, which many economists doubt is achievable, saying it was “cherry-picking” data when the country and its citizens are suffering.

One of the bases for the growth was the winter harvest, particularly wheat, which officials had projected to grow significantly.

In India, delayed sowing and loss of yield due to abnormal heat waves in the major wheat-growing states prompted the government to slap a ban on exports, except to its South Asian neighbours.

“The ban does not apply to Nepal, but it will definitely impact the prices of flour and flour-made products in Nepal,” said Regmi. “Though Nepalis do not widely consume flour, the ban in India could affect the food industry.”

A circular issued by the Indian government says that wheat is not banned in neighbouring countries, but this policy could mean that the private sector can import wheat by obtaining the government’s approval, according to traders.

On May 13, the Indian government prohibited all private wheat exports with immediate effect.

As wheat exports from India trickled to a stop, anxious importing nations have started putting in diplomatic requests as the list of countries seeking the grain continues to increase, according to Indian media reports.

About a dozen countries have reached out to the Ministry of External Affairs seeking clarification on whether their requests for Indian wheat would be fulfilled. As many as 47 countries have sought food grain from India, with many others hinting they would also need them.

The decision came amid widespread loss of yield due to abnormal heat waves in the major wheat-growing states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

Large parts of the crop had shrivelled due to the heat, and in certain cases, had become unfit for human consumption.

India’s official wheat production estimates for 2022-23 have been scaled down to 105 million tonnes from the 113.5 million tonnes estimated earlier.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu