Money

Nepal braces for deceleration in per capita income growth

Average income of Nepalis, which is growing at a sluggish pace, may not even rise at the current rate in the coming years if productivity fails to improve rapidly across various sectors, public investments do not go up and agricultural yields continue to remain low, a latest World Bank report says.

Rupak D. Sharma

Average income of Nepalis, which is growing at a sluggish pace, may not even rise at the current rate in the coming years if productivity fails to improve rapidly across various sectors, public investments do not go up and agricultural yields continue to remain low, a latest World Bank report says.

This is an indication that Nepal may not be able to join the grouping of middle-income countries by 2030 as per the target set by the government.

Nepal has been stuck in low-growth trap for years, with average economic growth hovering around 4 percent per year in the last 45 years. This growth rate may fall to 3 percent on average per year between 2017 and 2030 if business-as-usual continues, according to the report, ‘Climbing higher: Toward a middle-income Nepal’, launched on Tuesday.

The Washington, DC-based multilateral lending institution made the projection on deceleration in economic growth based on trend of investment, growth of human capital and improvement in productivity over the years.

If the economic growth rate falls to that level, average income of each Nepali will rise to mere $958 in 2030, which is not sufficient to graduate to the league of middle-income countries, says the comprehensive report, which has not only highlighted where Nepal lagged behind in the past but how to overcome challenges to spur economic growth.

Middle-income economies, as per the World Bank, are countries with a gross national income (GNI) per capita of over $1,045 but less than $12,736. Nepal’s per capita income currently stands at $730, with growth hovering around 2 percent on average per year in the last 45 years, which is the lowest in South Asia.

Nepal’s contemporary economic history suggests weak institutions and unsupportive policy choices have compounded Nepal’s challenges. These bottlenecks have weakened performance of the agricultural sector, which makes a contribution of around 30 percent to the GDP. These bottlenecks have also hit productivity growth and constrained public investment to around 4 percent of GDP per year, affecting capital formation.

As these problems created a binding constraint on economic growth, job creation tumbled, prompting large number of Nepalis to seek placements abroad.

The labour flight has raised the flow of remittances, which currently hovers around 30 percent of the GDP, and helped the country to lift people from the traps of absolute poverty.

“But large-scale migration is not a sign of strength, but a symptom of deep, chronic problems,” said Damir Cosic, the World Bank’s senior economist for Nepal and the lead author of the report, adding, “Remittances are compounding, not resolving, long-standing challenges.”

Increasing dependency on remittances, on the one hand, has reduced pressure on authorities to generate more productive employment at home and be more accountable in delivering results. Remittances, on the other hand, have fuelled consumption, raising imports and widening trade deficit, while causing the real exchange rate to appreciate.

It is said 10 percent hike in remittance income leads to a 0.5 percent appreciation in real exchange rate. Appreciation in real exchange rate favours imports and hampers exports.

“The impact [of this phenomenon] is possibly largest on low-value, low-margin manufactured goods, which account for a large share of Nepal’s export bundle,” says the report.

“All these factors combined mean Nepal, home to some of the world’s most industrious and adventurous people, could be stuck in low-growth, high-migration equilibrium for years to come.”

To avoid getting trapped in this quagmire, Nepal must boost investment and accelerate productivity.

Nepal, in fact, has savings necessary for high growth rates. Over the last 16 years, gross national savings of the country have averaged 34 percent of GDP, while capital formation-or investment in fixed capital assets, except land and cars-has stood at 22 percent of GDP on average per year. The result of this underinvestment is lower growth, says the report, adding, “Cross-country evidence suggest that countries aiming to grow at 7 percent or more annually, and double their real GDP every 10 years, require savings rate of around 35 percent of GDP.”

The savings accumulated by the country can be translated into investment if efforts are made. And higher investments lead to an increase in the level of potential GDP. But again investment is subject to diminishing marginal returns. This means an additional unit of input will generate additional output, but at a decreasing rate. So, productivity must go up. Or, simply put, more output should be generated through per unit of input.

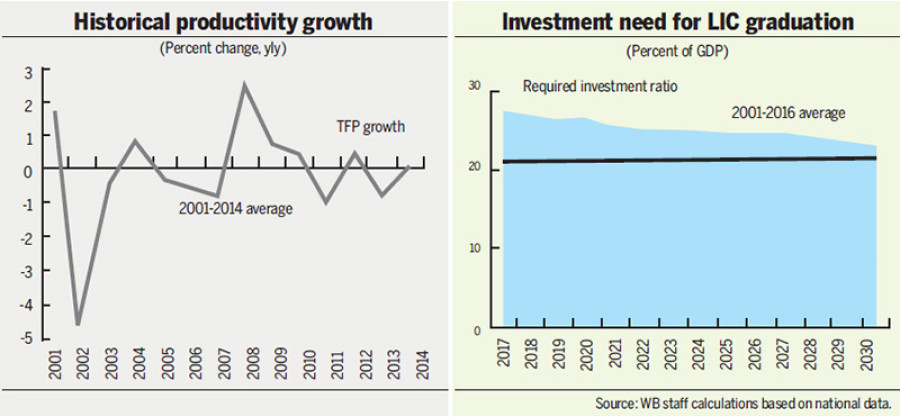

But the reality, according to the report, is that Nepal’s historical productivity growth oscillated around zero during the last 45 years and contributed nothing to overall growth when adjusted for growth of human capital, employment and labour force participation rates.

If productivity growth rises to 0.5 percent from 2017 to 2021-or increment of 0.1 percentage point per year-Nepal’s graduation to middle-income country will speed up by four to five years, says the report.

This projection was made based on assumption that investment-to-GDP ratio of Nepal stands above 25 percent per year in between 2017 and 2030. This kind of investment, which is quite difficult for Nepal to achieve, would boost per capita income of Nepalis by $22 per year and push per capita income to $1,026 by 2030.

“But along with this investment, Nepal also needs to intensify level of competition in sectors such as transport, logistics and telecommunications; reduce the cost of doing business; and invest in the skills of youths,” adds the report.

9.51°C Kathmandu

9.51°C Kathmandu