Miscellaneous

Wizard of the colours

Gaurab Thakali’s artwork is alive. The vibrant colours pulsate, as if breathing, and his fluid strokes undulate, as if constantly moving. Each piece of art has a distinctive palate, full of lush blues, vivid purples, deep greens and flamboyant yellows—

Pranaya SJB Rana

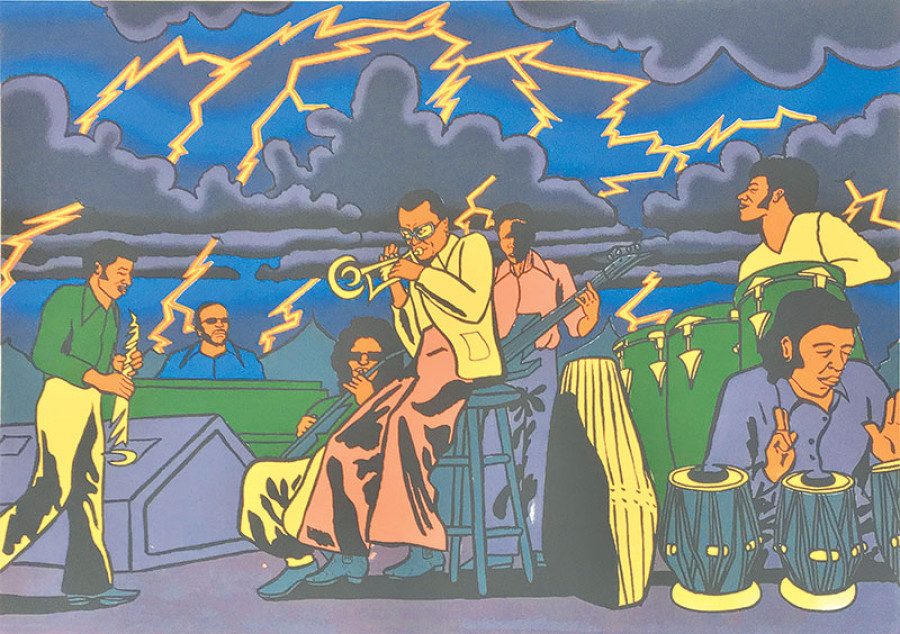

Gaurab Thakali’s artwork is alive. The vibrant colours pulsate, as if breathing, and his fluid strokes undulate, as if constantly moving. Each piece of art has a distinctive palate, full of lush blues, vivid purples, deep greens and flamboyant yellows—all bold, solid, contrasting hues. But there’s something rough and tumble about his art, the ends are not neat, the lines are not perfect. There’s a coarseness to his work, like an old blues singer’s scratchy vocals, tempered over the years by booze and cigarettes.

“The style and aesthetic of my work is of course very colourful. I subconsciously seem to have a set colour palette that I use which brings continuity to my style,” says Thakali. “Part of the reason other people like my work is because there always seems to be a lot of movement and some kind of atmosphere in the scene, like a party you’d really like to be at.”

Since moving to London in 2006, Thakali has built up an enviable portfolio, illustrating for publications like The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Guardian, Bloomberg Businessweek, Pitchfork and Variety. Most of his illustrations revolve around music—jazz, blues and hip-hop. He’s crafted album covers for jazz artist Oscar Jerome, a compilation of young London jazz artists called We Out Here and a foldout for jazz saxophonist Kasami Washington’s Heaven and Earth LP.

“My interest in jazz came about while I was studying for a degree in illustration at Camberwell College of Art,” says Thakali. “I was living with some friends who were studying jazz music at the Conservatoire in Greenwich. Living with them gave me a deeper understanding of the music, its history and culture. I could hear them practice all day and even drew them performing. It has sort of shaped everything I’ve drawn, painted and printed for the last eight years.”

Thakali’s affinity for jazz is evident in many prints he’s made of pioneering artists like Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, Wayne Shorter and Sonny Rollins. One silkscreen print of the avant-garde jazz composer and bandleader Sun Ra depicts him rising from an angry ocean frothy with waves, clad in regal robe and headdress, a red sun in the background. It is a fitting tribute to a man who was one of jazz’s great pioneers, especially in freeform and modal jazz, and also an Afrofuturist. His style is heavily influenced by old photos of jazz artists and “me wishing I could have been there to see them live,” says Thakali.

PHOTO Courtesy: DASHTI JAHFAR

Thakali’s work seems to speak to the black, African-American experience, inspired as it is by music from that culture. His work has been featured in an op-ed in The Guardian about American football star Colin Kaepernik’s protests in the US, a Guardian editorial about how ‘America’s heartland loses black people’ and a New York Times article on Martin Luther King, Jr. But his influences are many, from impressionism and post-impressionism to graffiti culture but also his native Nepal.

“My Nepali background has definitely inspired my work, to a certain extent,” he says. “For example, I frequently reference mountains, lush vegetation, sunrise, sunsets, etc. Some of these visual references you see as child remain with you forever.”

Thakali spent his formative years in Kathmandu, “listening to Nirvana and hanging out at pool halls with my mates,” he says. But he was never particularly interested in art. It was only when he started art school that he realised one could make a living as an artist. Pushed by his tutors, he began illustrating and began to make a name for himself. When asked if it was particularly difficult as a Nepali immigrant to establish himself in London as an artist, he replies in the negative: “It has been the opposite. It’s a blessing in a way as I have different references to draw from because of my Nepali heritage, be it the colours I use or scenes I draw. However, it is still a lot of hard work establishing yourself in this particular industry no matter where you are from.”

Thakali still makes periodic trips back to Nepal, as he still has a lot of family here. During his visit to Nepal in 2015, he spent a month drawing people and landscapes, which he developed into screenprints and printed on handmade Lokta paper. During that same trip, Thakali had brought along his skateboard and discovered a small skatepark in Pokhara. Daryl Dominguez, a London local, also happened to be in Nepal at the same time and when the two met up back in London at a skate haunt, they realised they wanted to help in some way. Together, they founded Skate Nepal, a non-profit that sells skateboards and gear to raise money for the Annapurna skatepark in Pokhara. They also collect donated skate gear for young kids in Nepal.

Combining his passion for art with skateboarding, Thakali also illustrates boards and designs skate gear for the UK-based company Skateboard Café. Thakali seems to have the kind of portfolio that every budding illustrator wishes they could. But Thakali is humble and down-plays his high-profile commissions. “It’s down to the world illustration.

Publications like these need the articles to be illustrated as clearly as possible and I think my work naturally can do that,” he says. “Then my style comes into play. The bright colours and movement in the pictures draw people in to picture themselves in the situation that’s happening in the drawings. You also have to be reliable and super easy to work with as they don’t have any time to guide you through things step by step.”

For young artists looking to break into illustrating and art, Thakali suggests that you produce a lot of work and try to develop your own style. The most important thing is getting your work out there, through social media or otherwise, so that people can see it. “Don’t be shy to show your work to friends and strangers even if you aren’t completely happy with it. People find it interesting to see how an artist has developed over the years,” he says. “Email art directors and finally get your work on social media. I’ve gotten so many commissions from people seeing my work on Instagram.”

For Thakali, it seems most things have fallen into place. He makes a living doing what he is passionate about and has earned the respect of the industry in the traditional way—through innate talent and perseverance. For many young Nepali artists, he’s a role model, someone to look up to and emulate, someone who’s made it.

Sun Ra. Silkscreen

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu