Miscellaneous

Life is elsewhere

Most recent theatre scripts read like adolescent diaries. The play consequently unfolds like CCTV footage of a person’s life. “There is no artistic distillation of life,” Rajan Khatiwada, a veteran theatre actor and artistic director of Mandala Theatre, lamented in November last year, during an interview with the Post, “If I want a raw slice of life, I will go to Asan Bajar.”

Sandesh Ghimire

Most recent theatre scripts read like adolescent diaries. The play consequently unfolds like CCTV footage of a person’s life. “There is no artistic distillation of life,” Rajan Khatiwada, a veteran theatre actor and artistic director of Mandala Theatre, lamented in November last year, during an interview with the Post, “If I want a raw slice of life, I will go to Asan Bajar.” Aghast by the apathetic state of Nepali theatre, Khatiwada and a few others conducted a month-long directors’ workshop, where they deliberated on the state of Nepali theatre while also crafting a play for stage.

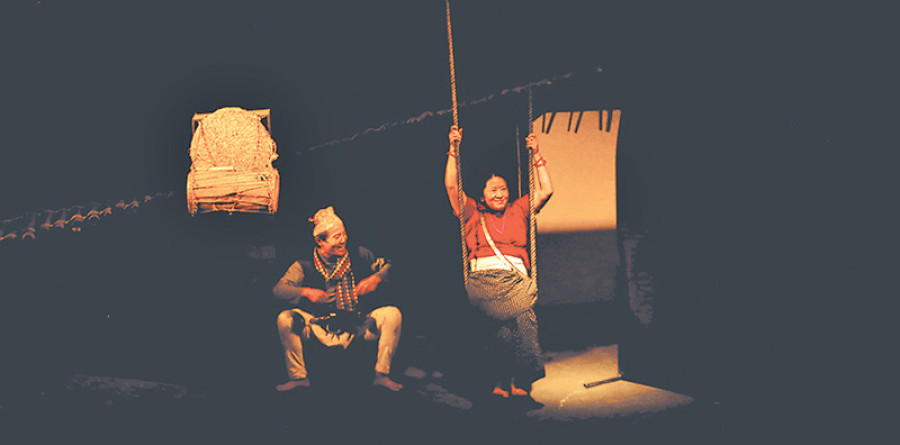

Khabar Harayeko Chitthi, which recently concluded at Mandala Theatre, was the result of that workshop. Jointly written and directed by 12 workshop participants, the play manages to save itself from the ‘too many cooks’ problem and goes beyond to offer new perspective on what is possible within the scope of black-box theatre. Chitthi, in the strictest definition, is not a single play; rather, it unfurls like an anthology of three different stories that revolve around the lives of those whose loved ones disappeared during the conflict years.

A crier in the hills of western Nepal regularly announces to villagers the presence of predatory birds in the village. “Save your chicks. The eagles are wandering around,” he informs his neighbours, and every time he makes the announcement, he breaks into tears because he was unable to save his son from the predatory grasp of the government. His story is that of displacement, of struggling to maintain normality in the wake of loss. In another, a husband who has a passion for music leaves his home to attend sakela, a traditional Rai festival with music and dance. In between dancing and celebration, a disruption arises and several disappear.

The story that follows is that of the wife trying to cope with her new reality. The third story depicts the life of a couple whose son has been abducted. At first, the couple seek the help of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (TRC), but when they receive no closure from the government, they live the rest of their lives imagining their son at different stages of his life: as an adult, as a husband and as a father.

The thread that connects all these disparate elements is the lack of closure. “Na ta saas cha, na ta laas cha, there is neither a breathing soul nor a corpse.” The sentiment of living in limbo is evoked by all these stories. These parts could be considered separately or they could be seen as the different stages of loss in a single journey of grief. The play explores the feeling that love and life is elsewhere, not with explanatory dialogues, but with a combination of different aspects available on stage and in the repetitive behaviour of characters.

Our lives are intricately tied with the ones we love. We rejoice in happiness or overcome sadness with those we share our moments of bliss and memory with. When death parts us from our loved ones, time allows us a way to staunch our tears. But when loved ones vanish, life becomes nothing more than a series of ‘what if’ questions.

The play reminded me of my own thulomamu, who lives in the expectation that her husband will return to her someday. She carries a passport size photograph of her husband wherever she goes. Not a morsel of food goes down without remembering her husband. She lives in purgatory; neither the bliss of a married woman nor the hell of a widowed wife is available to her. Her existence has been torn apart by a hurricane that swept away someone she held dearly. And Chitthi depicts the aftermath of such a hurricane that uprooted thousands of Nepali lives.

For a play that is inherently tied to the political struggles of the country, Chitthi refrains from favouring a particular side. It has often happened in the past that a production will tell you the cause, consequence and possible remedy for a social problem, thus transcending the nature of a play and becoming a policy prescription. Not passing judgement or hammering in a particular moral or ethical stance is a commendable aesthetic choice.

The success of the play lies partly in the fact that the story went through several rounds of critical edits and rewrites during the workshop. Perhaps this success suggests that original production can come out of sustained critical workshops. Ultimately, Chitthi stands as testament to the fact that a production does not have to trade poetic beauty to explore the socio-political history of a place.

“Plays often get bogged down by regurgitating the facts of a social condition,” Che Shankar, one of the play’s directors, said, “The stories of the play may not be true in the factual sense, but they bring forward the kind of truth that is only possible through fiction.”

The writer tweets at @nepalichimney.

22.37°C Kathmandu

22.37°C Kathmandu