Miscellaneous

Down to the river

Bruce Springsteen finds a way to put big emotions into the smallest of words. For any writer or poet, his songs are lessons in ‘why say in 10 words what you can say in two.’ Bare emotions do not have to be overwritten to be resonant.

Pranaya SJB Rana

During his concert performances in the 80s, Bruce Springsteen would often tell a story, long and rambling, about his fractious relationship with his father. Sometimes, the story ended on a good note, with his hard-nosed father accepting the life his singer-songwriter son had chosen. Other times, it didn’t go so well. Accompanied by the strumming of a guitar and soft synthesisers, the story would be heartfelt and nostalgic, told in a way that is quintessentially Bruce Springsteen. A silence would follow from the thousands in attendance once the story ended and in the space of that dark hollow, a mournful harmonica would strike up, echoing in the stadiums Bruce frequented, signalling the beginning of the classic song 'The River'.

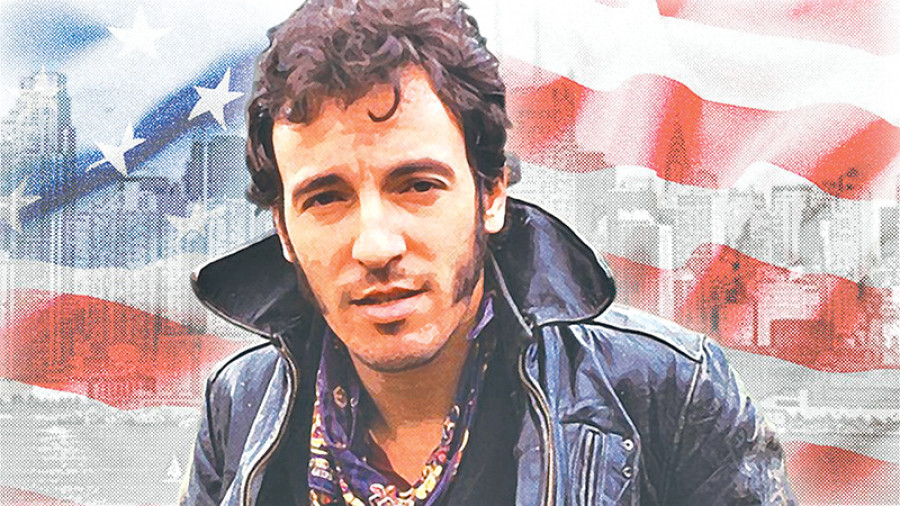

I discovered Bruce Springsteen in my teenage years and assumed, like everyone else, that he was a nationalistic, jingoistic, bombastic singer from the American heartland, all star-spangled banner and Chevrolets, belting 'Born in the USA' to a stadium of rednecks. It took a few more years to give him another chance and really listen to 'Born in the USA'. And again, like most people, I discovered that the song was not nationalist at all; in fact, the chorus was the refrain of a Vietnam War veteran, unemployed, scared and alone, crying out for a country that had used him up and cast him aside. I heard these lines: “Down in the shadow of the penitentiary / Out by the gas fires of the refinery / I’m ten years burning down the road / Nowhere to run ain’t got nowhere to go” and began to wonder how a singer I’d considered a meathead had come to write something as poetic as this.

How could Bruce Springsteen, perhaps the most definition of the American Rockstar, resonate with a young Nepali boy, who owned neither a car nor had ever careened down a highway? It was simple, Bruce was a poet and his honest salt-of-the-earth lyricism appealed more to me than the Bukowski my peers were reading. Here was a singer, misunderstood and miscast as an uncritical chest-thumping American, but in truth was a sensitive poet, writing about dreams, heartbreak, love, loss and betrayal. As someone who had just started writing honestly, trying to discard the shackles of simulating the writing I admired, Bruce Springsteen spoke to me.

Take, for instance, the opening to another classic song, Thunder Road: “The screen door slams / Mary’s dress waves / Like a vision she dances across the porch / as the radio plays”. The image is one so simple and yet so resonant, a door shuts behind a girl as she dances, her dress undulating and the radio playing. It is a figure distilled into one strong, evocative image, the hallmark of any good writing, where a picture is drawn and it lingers in the mind like an imprint. Later in the song, towards the very end, appears another series of images, one after another, that leaves me breathless:

“There were ghosts in the eyes / of all the boys you sent away / They haunt this dusty beach road / in the skeleton frames of burned-out Chevrolets / They scream your name at night in the street / Your graduation gown in rags at your feet / And in the lonely cool before dawn/ You hear their engines roaring on / But when you get to the porch they’re gone.” That last couplet, where Mary is lured to her porch in the “lonely cool before dawn” by the promise of freedom implicit in the roaring engines, but she’s missed her chance, creates an indelible image in my head and leaves me wondering, marvelling at the unsophisticated structure, the direct honesty of the phrasing and the poetry with which the plain words are strung together to create something much larger than the sum of their parts.

As I grew up and the more Bruce Springsteen I listened to, the more I learned about the economy of words and the power of phrasing. I have imbibed more about vivid imagery from Bruce Springsteen than perhaps any other writer. No metaphor, not much analogy, just the creation of a scene and a character, detailed enough to appear in your head but loose enough that everyone is able to imagine their own version, just like a phantom. Take these for example, “Pour me a drink, Theresa, in one of those glasses you dust off / And I’ll watch the bones in your back like the stations of the cross (I’ll Work for Your Love)” or “Now our love may have died and our love may be cold / But with you forever I’ll stay / We’re going out where the sands turning to gold / So put on your stockings baby / Cause the night’s getting cold (Atlantic City)”. In the first instances, a scene is sketched in the mind of the reader (or listener), evanescent but also lingering, just like any good song or poetry: the bones of Theresa’s spine and shoulders outlined like a cross as she bends to pour a drink. In the second, a haunting illustration of a certain kind of love: a gentle reminder to put on your stockings, despite a love that may have died, because the night’s going to get cold.

Like Hemingway, Springsteen finds a way to put big emotions into the smallest of words. For any writer or poet, his songs are lessons in ‘why say in 10 words what you can say in two.’ Bare emotions do not have to be overwritten to be resonant: “Sometimes it’s like someone took a knife, baby / Edgy and dull / And cut a six-inch valley / Through the middle of my soul (I’m on Fire)” or “He tried sellin his heart to the hard girls over on Easy Street / But they sighed, ‘Johnny, it falls apart so easy / And you know hearts these days are cheap’ (Incident on 57th Street)”.

So often I found myself listening impossibly to this man who spoke of things that I had never experienced, and I didn’t ever long for. Instead, I heard the ache for freedom and a desire to be someone behind his dreams of fast cars speeding out on highways that led out into the night. I heard the yearning of a heart that had loved too fast and too much, a soul that sought redemption from past sins, a life caught up in circumstances beyond its control because of decisions once made in a world uncaring and indifferent, no matter how broken or lost you are.

I’ve listened to 'The River' countless times, and it is always that live version with the tale about his father that I keep coming back to. In the split-second silence before the harmonica soars like a bird seeking flight, I find myself existential—what do I love and what do I yearn for. 'The River' is a song about being trapped in situations you cannot get out of because of a mistake you made. But you still hold on to the hope that perhaps there is something better out there, even if that hope is built on memories. The river in the song is a metaphor for that hope and it is the river’s fullness, its constant flow that inspires faith. In the end, even the river dries up and all we are left with are memories:

“But I remember us riding in my brother’s car / Her body tan and wet down at the reservoir / At night on them banks I’d lie awake / And pull her close just to feel each breath she’d take / Now those memories come back to haunt me / They haunt me like a curse / Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true / Or is it something worse”.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu