Miscellaneous

Trekking towards modernity

In 1959, I returned home from Banaras to Amarpur. While I was there, one of my step-uncles, Baburam Aryal, came to visit. He was working in Kathmandu as a clerk in the secretariat office of Nepal’s first elected parliament and I had long conversations with him about my education and experiences in Banaras, what he was doing in Nepal’s civil service and what life was like in Kathmandu.

Kul Chandra Gautam

In 1959, I returned home from Banaras to Amarpur. While I was there, one of my step-uncles, Baburam Aryal, came to visit. He was working in Kathmandu as a clerk in the secretariat office of Nepal’s first elected parliament and I had long conversations with him about my education and experiences in Banaras, what he was doing in Nepal’s civil service and what life was like in Kathmandu.

Baburam uncle told my father I was too bright to be studying just Sanskrit and theology. The world was changing, he said. The British Raj had ended in India and many countries were throwing off the yoke of colonialism. The winds of change were sweeping even Nepal, following the fall of the century-old Rana regime. He was excited about Nepal’s first elected Nepali Congress Party government under the charismatic leadership of BP Koirala.

He said the new government was introducing a modern “English” education system that would be more relevant for building a ‘New Nepal’. He urged my father to move me from the “outdated” Sanskrit-based education system to the modern “English” system. In those days, “English education” meant the educational system the British had introduced in colonial India with the aim of producing clerical staff with some knowledge of the English language.

My father and I were struck by this description of the changing world and changing Nepal. While we couldn’t fathom everything he said, my father felt that someone who worked as a government officer must be right and agreed to move me to the “English” education stream. As there were no such schools in our area, Baburam offered to take me to Kathmandu, look after me and arrange my education there. Thus began my journey to the Capital and the new world of “English” education.

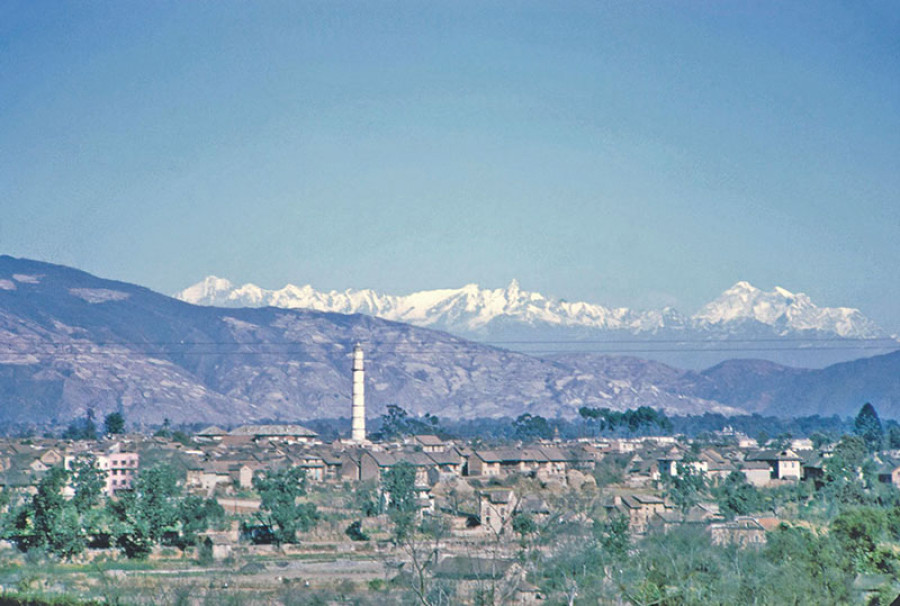

In those days, the journey to Kathmandu was quite an adventure. It would have taken 13 days walking from Amarpur, so we decided to take a “shortcut” via India. We first trekked for five days to Butwal. From there, we took a bullock cart and rickshaw to the Indian border town of Sunauli. We then travelled by train for two days and two nights, passing through Gorakhpur, Muzaffarpur and Raxaul, to re-enter Nepal at Birganj. From there we took a train to Amlekhganj and then walked past Bhimphedi to the high plateau of the Chitlang Valley and the picturesque Chandragiri hills. Finally, a steep walk down to the suburban settlement of Thankot brought us to the edge of Kathmandu. This “shortcut” took nine days.

I stayed with Baburam and his wife in their rented room in Galkopakha near Thamel. I was enrolled at the nearby Shanti Vidyagriha School in Lainchaur. The school found it difficult to place me because I didn’t know English, although my Nepali, Sanskrit and arithmetic skills were quite good and I was mature for my age. So, although I was 12 years old and should have been in fifth grade, I was initially placed in the third grade. I found all the subjects, except English, relatively easy. So, I studied hard, focusing on English. In the year-end exams I topped the class and got a “double promotion” to the fifth grade.

For someone coming from a remote village, Kathmandu was an exciting city. I witnessed extraordinary scenes, like something out of fairy tales. One was the State Visit of Queen Elizabeth II in 1960. The whole city was spruced up. The road from the airport to the Royal Palace was decorated with colourful banners. I joined the crowd lining the road as the British Queen and King Mahendra along with Prince Philip and Queen Ratna arrived in horse-drawn carriages, with the Royal Nepalese Army band dressed in Scottish kilts played the bagpipes to welcome the royal visitors. The pomp and circumstances were breathtaking to a boy from the hills.

Another memorable occasion of a completely different nature was King Mahendra’s royal coup d’etat on 16 December 1960, overthrowing the elected government of BP Koirala. I recall an eerie silence punctuated by the sound of army vehicles rumbling around town, and hush-hush rumours that the PM and other leaders had been arrested. Baburam uncle came home from his office shocked and saddened. He was glued to the radio as the announcer explained that the King had to take this step to “save the nation from impending anarchy and misrule.” Although I didn’t understand the situation, it was clear that something inauspicious had happened. I realised then that the King of Nepal, considered by many to be the incarnation of Lord Vishnu, was not as holy or infallible as we had been conditioned to believe.

Although Kathmandu was stimulating, I was learning a lot and my schooling was going well, I wasn’t feeling very well physically and found the winters too harsh. So when I went home in 1961, instead of returning to Kathmandu, my parents agreed that I should go to Tansen, Palpa to continue my studies.

13.58°C Kathmandu

13.58°C Kathmandu