Miscellaneous

brave new World

There is a constant refrain among middle-to-upper class Nepalis, especially those who’ve returned from abroad—the Nepali film industry is moribund. They constantly bemoan the lack of quality fare that rivals films produced by India’s parallel cinema or even Nepal’s own thriving documentary scene led by luminaries like Kesang Tseten, let alone European art school films or new wave Asian cinema.

Pranaya SJB Rana

There is a constant refrain among middle-to-upper class Nepalis, especially those who’ve returned from abroad—the Nepali film industry is moribund. They constantly bemoan the lack of quality fare that rivals films produced by India’s parallel cinema or even Nepal’s own thriving documentary scene led by luminaries like Kesang Tseten, let alone European art school films or new wave Asian cinema. This is not a complaint lacking in veracity, but it is myopic. Even though Nepal’s film scape is overwhelmed with films like Chhakka Panja and Nai Na Bhannu La, which are among the most popular Nepali films ever made, grossing crores, these films resonate with the Nepali filmgoing public on a level unseen. They are funny, colourful and entertaining, but they are also hackneyed and full of caricatures. In a manner, they ape the Bollywood films of the 90s and the 2000s, with their broad strokes comedy and their focus on stock characters and snappy dialogue over narrative drive, smart plotting and deep characterisation.

This is not to say that these films are bad in any way. Clearly, they resound with a mass audience that is going to the movies more than ever. These films provide entertainment to the Nepali population on a level few others have been able to. There are, however, other kinds of films also being made, though the public might not be lining up to see them. Some of the most interesting and affective films have come out of Nepal in recent years. And though they haven’t found an audience quite like those afore-mentioned films, they are by no means flops. They play to full houses and have a decent theatre run. These include films like Saanghuro, Kabaddi, Talakjung vs Tulke, Pashupati Prasad, Bijuli Machine, among others. These films act as a creative counterweight to an industry bloated with popcorn fare. They are not purely art films aimed for a festival circuit, but they are not completely commercial ventures either. They play a balancing act between artistic vision and commercial ambitions. After all, who says a great film can’t also be popular?

These films did not appear out of nowhere. They had precedents and influences to draw from trailblazers. In this column, I would like to discuss four contemporary films, purely personal choices, that I believe helped (and are helping) push Nepali film towards a more artistic and creative direction. Some of them were commercially successful while others less so. But all of them attempted something artistically interesting and signalled the advent of a different approach in the industry.

Kagbeni (2008)

No discussion on the evolution of the contemporary Nepali film industry can be complete without Kagbeni. Directed by Bhusan Dahal, Kagbeni set a new benchmark in the realisation of Nepali film. Shot digitally, the film won praise for its gorgeous cinematography, courtesy of Bidur Pandey, and introduced the masses to the star that would be Saugat Malla. Reliably assisted by Deeya Maskey, Pooja Gurung and even popstar Nima Rumba, the film received praise for its acting, even though its script left something to be desired. Despite its faults, Kagbeni marked a sort of turning point for the Nepali film industry. With its rejection of traditional song-and-dance sequence, over-the-top acting, slapstick comedy and cliché plotlines, Kagbeni showed that Nepali film could provide something different, a vision that was not contingent upon what was happening next door. The filmmakers seemed to look towards the West, borrowing cinematographic, directorial and editing cues.

Ten years later, Kagbeni feels dated, not just because technology has moved on but Nepali films have too. The brilliant vistas sketched in the film have become another cliché, which films like Jerry have attempted to capitalise on. With the years, Nepali films have also understood the symbolic meaning of locale. Whereas in Kagbeni, the Mustang landscape is merely a backdrop; the story might as well have been set anywhere. Still, the aesthetic direction set out by Kagbeni was one that subsequent films have attempted to follow, for better or worse.

Kalo Pothi (2015)

Before Kalo Pothi, there was Highway;

only Highway was not as good as Kalo Pothi. Both films were backed by foreign producers and both saw their debuts at international film festivals. But while Deepak Rauniyar’s 2012 Highway was a hodgepodge of plots and characters, Kalo Pothi was restrained, assured and focussed. Min Bahadur Bham’s tale of two kids from Mugu in the midst of the civil war is, in my very subjective opinion, the best film to have come out of Nepal so far. The two child leads are impeccable, the cinematography is beautiful but not showy in the manner that Kagbeni was, and the plot engaging but elliptical.

Kalo Pothi, however, is an ‘art film’, in that it is not aimed at a mass audience. This is most obvious in the film’s decision to retain the regional Mugu dialect, such that even native Nepali speakers need subtitles, along with the use of non-actors, and the ambiguous, non-conventional narrative. The restraint that Kalo Pothi shows in employing its stunning locales only adds to its strengths. Where a more conventional film might have used the beauty of geography a la Kagbeni, Kalo Pothi holds off on wide-angle landscapes for the most part, allowing the story to dictate when and where the greater geography makes an appearance. Kalo Pothi is a challenging film. It requires work on the part of the viewer and so, actively involves us in the making of the film’s narrative. In the deeply humanistic tradition of the late great Iranian auteur Abbas Kiarostami, whose Where is the Friend’s Home this film echoes, Kalo Pothi does not sacrifice its characters to mere plot or aesthetics; it allows all elements of the film to stand on its own and by doing so, elevates the film to something more than entertainment or social commentary.

Loot (2012)

Coming just four years after Kagbeni, Loot was an eye-opener for many, especially young urban Nepalis not interested in the contemporary offerings of mass market Kollywood. With its frenetic pace, established in the opening scene itself, the film took much from contemporary Hollywood—slick directing, fast cutting, sweeping camera moves, time lapses and a not-too-surprising plot twist. Loot was young, urban and hip. It was also smart and memorable, with the character of Haku Kale taking on a life of its own.

Loot had its faults. It relied a tad too much on technical wizardry and less on narrative arcs and pacing. Saugat Malla pretty much carries the film, with the other actors leaving something to be desired. But the film introduced Nishchal Basnet, a rising star who would go on to make other well-received films, though none as popular as Loot. Basnet’s subsequent offerings, as director, actor and producer, are better realised, especially inTalakjung vs Tulke. Loot 2, the sequel, was a very noticeable and disappointing low.

Loot did what Sano Sansar failed to do a few years earlier and what Dil Chahate Hai had done for Bollywood, echoed with a hitherto untapped market of young urban dwellers. But it also proved that Nepali films did not need to be formulaic. They could take risks and by doing so, establish trends.

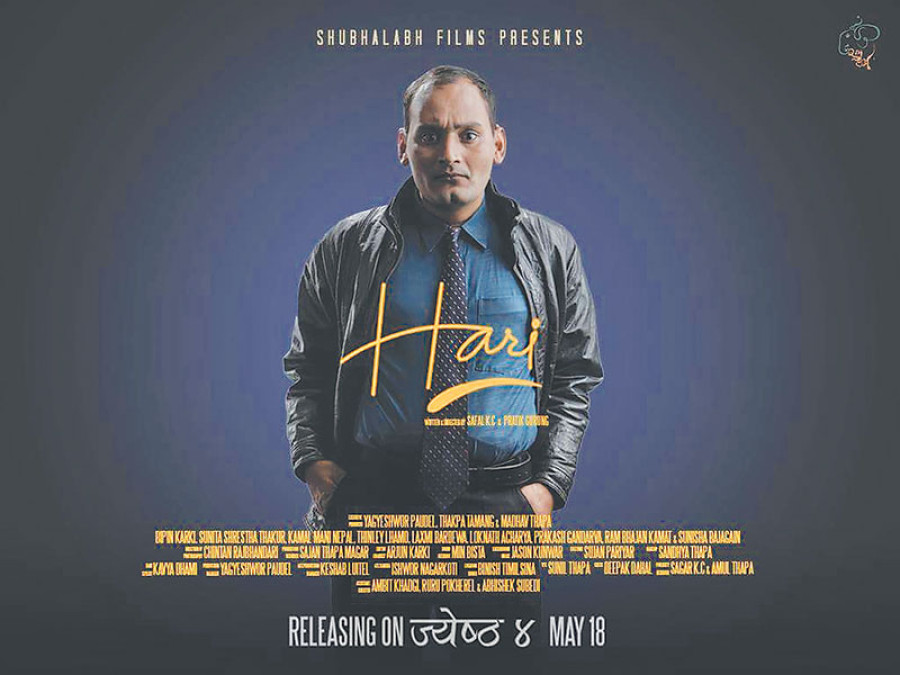

Hari (2018)

The very recent Hari is a treat of a film. It is visually stunning, superbly acted and directed with flair and aplomb. Written and directed by Pratik Gurung and Safal KC, Hari is that rare Nepali film that manages to entertain, illuminate and also present a cohesive artistic vision. It is what Bhaskhar Dhungana’s 2014 offering Suntali could have been. Led by a brilliant Bipin Karki, who plays the titular Hari among a few other characters, the film owes its aesthetic to Western directors, like Wes Anderson, whose carefully composed sets and distinctive colour palette are emulated. Karki is a delight to watch as the very non-traditional lead, a mousy, conservative Bahun who is a “man of schedule”. His range is in full display, playing a number of other characters, all with skill and style.

Hari has many strengths but also a few flaws. It is aptly directed, and the narrative drive is neatly plotted. But Hari’s arc is confused, and the ending is where it falters. The film doesn’t know what it wants to be, whether a quirky character study or a gritty dark comedy. It starts out as the former and slides very fast towards the end into the latter. For such a sparsely populated film that relies heavily on the lead actor to carry the story forward, the ending undoes much of the characterisation that the film sets up.

Still, Hari is one of the most entertaining and vibrant Nepali films I have seen yet. It takes risks by establishing a strict aesthetic and sticking to it. It eschews tradition by giving up on song-and-dance and an ensemble cast. It starts off beautifully, performs a number of very acrobatics but fails to the stick the landing. The ride, however, is well worth it.

Post-script

What drives these four films is a willingness to follow an artistic vision that is seemingly at odds with what is currently popular in the mainstream. Supported by producers willing to take the hit and actors willing to invest completely in their roles, they provided alternatives in an industry replete with formulaic crowd pleasers. While it is no doubt a great thing that so many are going to the movies, I cannot help but wish that more people had gone to see films like Hari.

For naysayers who prefer to flock to watch the latest Sanju or the latest Antman and yet unceasingly complain about the quality of Nepali films, I would urge that you pay a visit to the theatre the next time an interesting Nepali film comes around. Filmmakers who go against the grain deserve support, for without them we might as well be stuck forever with the latest iteration of a stock film with a pretty female actress, lavish song-and-dance sequences, slapstick comedy and broad caricatures. While such films have their place, we all suffer if they are all we have.

10.21°C Kathmandu

10.21°C Kathmandu