Miscellaneous

In search for justice

In The Girl from Kathmandu, a decade long investigation reveals how Nepali youth are dispensable cogs in the global machinery

Sandesh Ghimire

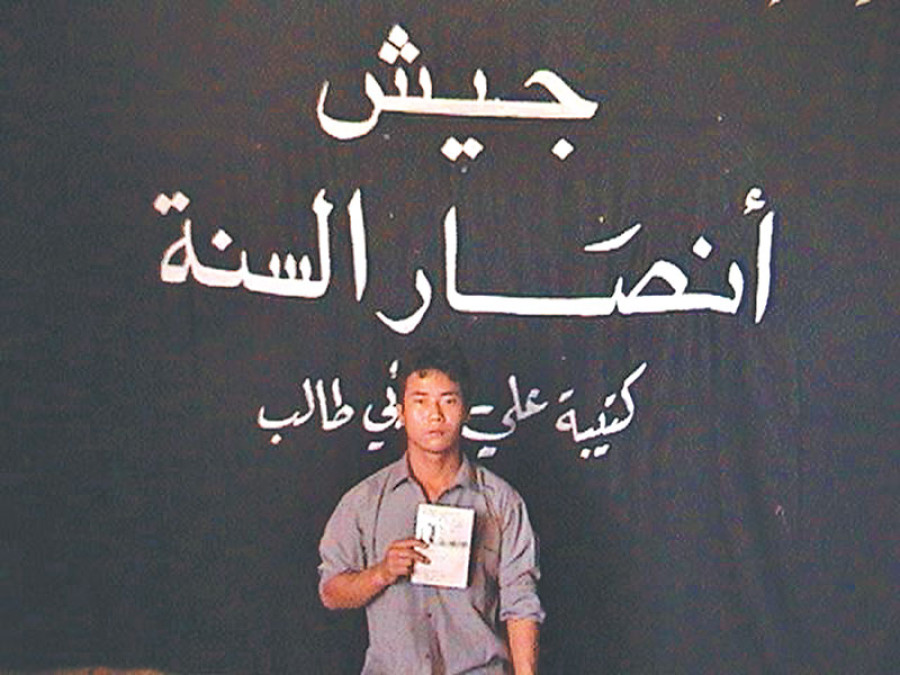

In 2004, Nepal made headlines the world over after 12 of its citizens became part of a televised killing—an act that would be described as one of the cruelest moments of the American invasion of Iraq. Despite low connectivity to the Internet and the virtual absence of social media, the execution video spread like wildfire in Nepal.

In the immediate aftermath, in Nepal, rioters destroyed the offices of manpower agencies for their part in siphoning Nepali youths to become dispensable labour abroad. The situation calmed, and manpower agencies rebuilt their offices and went back to business. But the question slingered: Why were Nepalis killed for being US supporters, even though Nepal had declined George Bush’s invitation to join the ‘coalition of the willing’? How had young men from some of the most remote parts of Nepal come to be crucified in a war where they had no allegiances?

In searching for the answers, in The Girl From Kathmandu: Twelve Dead Men and a Woman’s Quest for Justice, journalist and author Cam Simpson discovers a global supply chain, which funneled in impoverished Asians “who were often deceived, exploited, and put in harm’s way in Iraq with little protection or regard for their lives” so that the Iraq war was “fueled, fed and running.”

False employment promises had taken the twelve men to Jordan after which they were brought into Iraq, like contraband goods, to work for Kellogg Brown and Root (KBR), a multinational corporation which had monopoly over US war contracts since the Vietnam War in the sixties.

“Deception, fraud, and coercion were widespread with regard to sending men to work in a war zone through US subcontractors,” but, Simpson writes, “There was no single villain pulling every string from the top; instead there were several individual actors making up an overall chain of conduct. It was an inherently transnational enterprise, making use of both a supply chain extending across multiple countries and an extensive transnational network to succeed. And it was run through a thick web of recruiters, contractors, subcontractors, parent corporations, and subsidiaries crossing jurisdictions, countries and continents.”

Simpson’s investigation discovers that KBR is a subsidiary of Halliburton Corporation where Richard Cheney, one of the fiercest advocate for the Iraq occupancy, had served as the CEO before resigning to become the Vice President of the US during the Bush administration.

After Simpson’s initial investigation, he published a report in the Chicago Tribune that encouraged human rights lawyers to file lawsuits on behalf of the 12 grieving families. But “establishing the truth is one thing. Satisfying the rules of evidence in a court, especially against a well funded adversary is another matter entirely.” In Simpson’s analysis, the ‘overall chain of conduct’ allowed KBR to exploit several legal loopholes to continue forestalling the litigation against them.

The litigation continued for over a decade. Eventually, forced to use another case as precedence, the presiding judge dismisses the case because “foreign government and individuals could be sued under the law, not corporations.” Nonetheless, while giving the verdict in favour of KBR, the judge writes, “the Court again notes its profound regret at the outcome of the action. The crimes that are at the core of its litigation is more vile than anything else the court has previously confronted”…points to the dismal reality of how legal restrictions allows corporations to escape punishment.

Corporations can be considered a legal “person” when in need for protection but let go of that identity when “they want to escape potential liabilities.” Thus begging the question: What kind of judicial restructuring is necessary in order to bring corporations under the scaffolding of the law?

But given the present circumstances, the economy of exploitation will only subside when those pulling the levers of power have a moral reckoning. Until that unlikely day, for the economy’s sake, governments of developing countries like that of Nepal will be forced to supply dispensable labour. In the years since the massacre, the only bargaining power that the Nepali government has developed is the ability to advocate to return the bodies of the deceased. For Nepali readers, Simpson’s investigation also serves as a reminder for not doing what is in Nepali government’s and society’s immediate power: Stopping the ostracisation of widows. The eponymous woman, Kamala, struggles for a decade in search for dignity that was lost simply because her husband had been killed.

The book chronicles a global crisis, one where Nepal, as a country, might not have a lot of agency in solving the problem. We must ask of ourselves, what can we do to reduce the hurt of those who bear the brunt of the pain?

Twitter: @nepalichimney

27.63°C Kathmandu

27.63°C Kathmandu