Miscellaneous

A gloomy classic comes alive

In a span of two months, two separate adaptations of Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters have been staged in Kathmandu’s theatres. The first one was the English adaptation, Three Sisters, staged at the Kunja Theatre in March, and there is an ongoing Nepali adaptation, titled Tin Bahini, at Shilpee Theatre, Battisputali.

Sandesh Ghimire

In a span of two months, two separate adaptations of Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters have been staged in Kathmandu’s theatres. The first one was the English adaptation, Three Sisters, staged at the Kunja Theatre in March, and there is an ongoing Nepali adaptation, titled Tin Bahini, at Shilpee Theatre, Battisputali.

I am delighted to report that even after multiple viewings, Three Sisters (Tin Bahini) feels new; as if you were experiencing the world anew with the senses of a newly-born baby. This happens because a second time audience will be able to move beyond the first impression and read between the lines.

The first obvious judgment one makes, or a ‘theme’ that is identified, is how the characters consider migration as the panacea of all their problems that they perceive to be having. The eponymous three sisters have a rigid idea that moving out of the provincial town and into the capital will solve their crises and bring all their desires to fruition. But because the protagonists are not able to fulfill their desires, they use their longing as hope, as a way to wear out the days. That is, until the hope crumbles under the weight of time, and doom looms like an overhanging cloud.

In the source material, Chekhov uses many Judeo-Christian connotations to add layers to the story. However, Christian imagery in the English adaptation in March obstructed a Nepali audience from seeing the intricacies of the play. Tin Bahini makes cultural adjustments that provide better access, making the time spent at the theatre enjoyable as well as reflective. When the Carol becomes Deusi, a Nepali audience will watch the play not as a bystander, but as a family member. The hopes and struggles projected by the actors become that of a viewer and in the end, one walks out of the theatre with a feeling of emptiness that occupies your mind. You wonder: Is my life going to culminate without love, without a sense of belonging, in meaninglessness and restlessness that the three sisters feel? Or will I be able to attach myself with a purpose and keep prodding along?

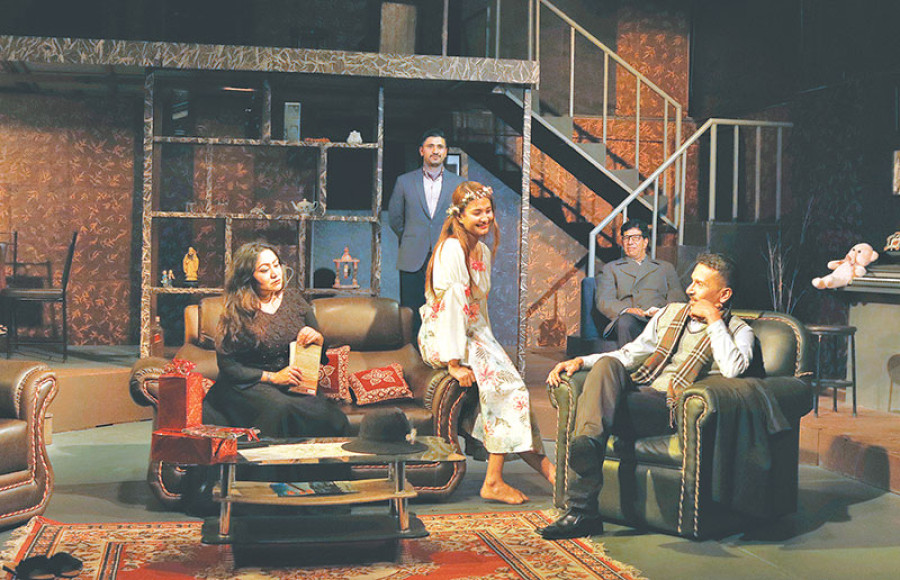

Walking out of the theatre, you feel uprooted, as if you have already arrived at the end of your life. This eeriness was achieved by a combination of a sound literary translation, along with well-suited acting, a stellar set and plenty of sensual cues. For instance, when a fire engulfs a part of the neighbourhood the play is set in, there are traces of fire smoke in the theatre, making the audience suffer through the fire as much as the characters on set. Similarly, in the two-storied set, scenes are blocked in a way that allows for various level of engagement from the audience. Most of the scenes where characters are experiencing emotional outbursts happen in the bedroom, which is in the second storey of the set. As a result, the audience has to look up, allowing some distance to reflect on the peaks and bottoms of a character’s emotional journey.

The way the actors moored themselves to their characters helped shape the outlook of the audience. A drunk doctor is clumsy without being histrionic and the military men, even when drunk, have a firm control over their bodies, even if they don’t have control over their mouths and behaviour.

Tin Bahini serves as a reminder to how so many factors are meticulously woven together to tell a story. This simple truth is often overlooked and it would have perhaps been missed had there not been another production of the same play to make a comparison with. The English adaptation had raised the standard of production value, but the Nepali adaptation has paid attention to finer details, thus bringing the Russian play to a Nepali backyard.

The good qualities of Tin Bahini do not overshadow its shortcomings, however. The original Three Sisters is a four act, almost three-and-a-half-hour-long play, but this Nepali adaptation has been squeezed into an hour-and-a-half long production. At times it feels that what comes out of a character’s mouth is not the dialogue itself, but a summary of a scene that has been cut out. As a result, because some of the characters don’t get the same length of character development, some dialogues don’t quite make sense. For instance, in Chekhov’s original, the middle sister constantly repeats the lines of a poem by Pushkin, and when she does so upon losing her lover, there is a surreal effect. In the Nepali adaptation, Laxmi Prasad Devkota, “Yatri”, replaces Puskin but the sister does not have the same kind of obsession with the poem. Consequently, when she repeats the lines during the final scene, it comes out of the blue. Other than the minor translation glitches, rendering some of the dialogue to be choppy, the play is well made and deserves the attention and applause of a theatregoer.

Tin Bahini belongs to the healthy train of plays from around the world being ferried to Nepali theatres. The effect of the ongoing wave of translations has been two fold. Tin Bahini is chipping away the cultural barrier that comes with any kind of translation. On the other hand, staging of classical foreign plays raises the standard of theatre going experience in general. Audience learn not only to seek entertainment but also a tool for retrospection—a challenge original Nepali productions oftentimes struggle to meet.

Tin Bahini is being staged at Shilpee from 5:30 onwards until May 26 (except for Tuesdays). Matinee show starts at 1:00 on Saturdays.

22.37°C Kathmandu

22.37°C Kathmandu