Miscellaneous

The democratization of the Nepali language

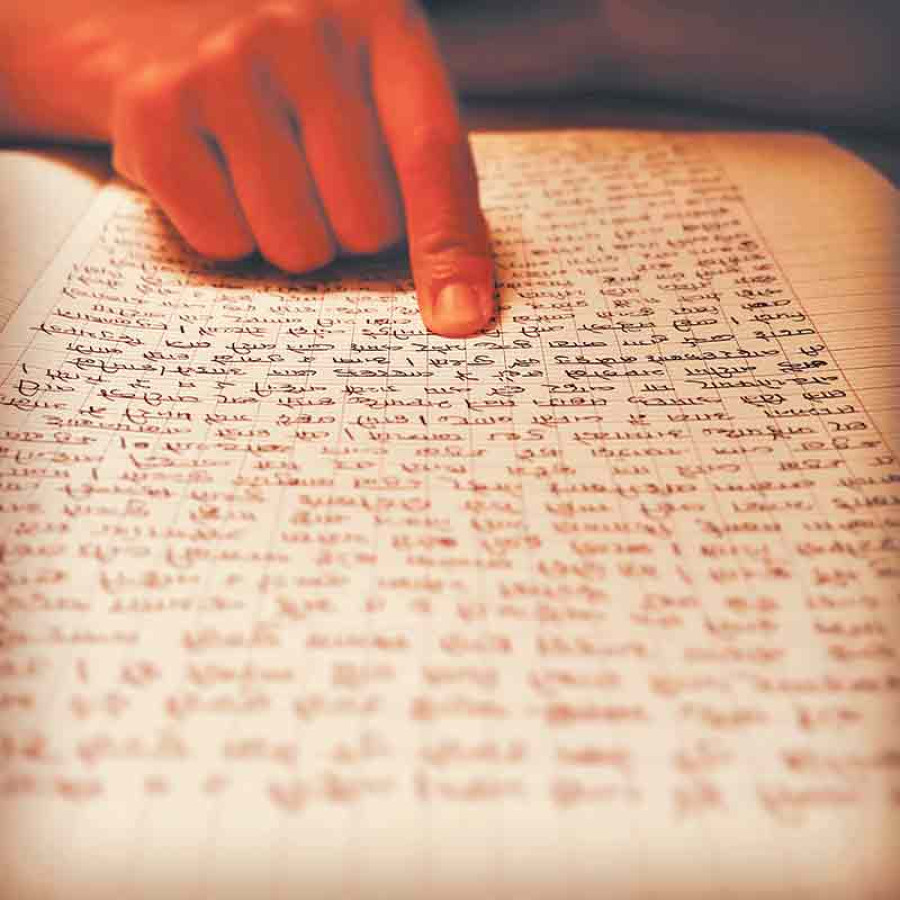

English speakers who learn Nepali discover, and quickly, that there is a marked difference between the language’s spoken and written forms. Those who study Nepali literature also discover, more gradually, that the stories that are told orally are at least as poignant, if not more so, than those that are written.

Manjushree Thapa

English speakers who learn Nepali discover, and quickly, that there is a marked difference between the language’s spoken and written forms. Those who study Nepali literature also discover, more gradually, that the stories that are told orally are at least as poignant, if not more so, than those that are written.

English speakers who learn Nepali discover, and quickly, that there is a marked difference between the language’s spoken and written forms. Those who study Nepali literature also discover, more gradually, that the stories that are told orally are at least as poignant, if not more so, than those that are written.

Spoken Nepali is filled with local idioms that vary from locale to locale, infusing conversation around the country with a particular poetry and pleasure. One of the great marvels of traveling in Nepal, for Nepalis, is encountering the richness of the Nepali language itself. Usage varies from east to west, north to south, and even from community to community in the mid-hills. The diction is invariably low, with many words from other languages mixed in. The turns of phrase are evocative, and often very touching. The grammar is flexible and accents differ widely; spoken Nepali is extremely informal. This makes it approachable to outsiders, including to non-native speakers within Nepal. Non-native speakers from abroad who take immersion courses can launch into conversation within weeks.

By contrast, written Nepali is formal, requiring rigorous study. The rules of grammar are rigid; there are only correct and incorrect usages. Though there is no single Nepali dictionary that completely standardizes spelling, the attempt to create one is ongoing at the Nepal Academy. The diction of written Nepali is high, with many words rooted in Sanskrit. For this reason alone, many ordinary Nepalis struggle to understand Nepal’s newspapers and official documents. Outsiders are firmly excluded from the Nepali language in its written form.

I began to read Nepali literature as I started off as a creative writer in the mid 1990s. Many of the great writers of pre-democratic Nepal were still alive then: Mohan Koirala, Ramesh Vikal, Parijat. It was not easy for me to approach their work, because in my journey to adulthood in the United States, I had lost the fluency that I had acquired as a child in Kathmandu. I had to relearn Nepali under the tutelage of the poet Manjul, who, as my good fortune would have it, was extremely adept at teaching it as a second language. He quickly identified my weak spots and helped strengthen my grasp of grammar. My comprehension, however, lagged far behind. Even after I regained my fluency, reading in Nepali—my mother tongue—remained daunting because of the Sanskrit words mixed into the texts I was reading. (During this time I often wondered whether I would be able to write at all if my first language, English, were riddled with as many Latin words.)

I now think of those early years of reading as my introduction to Nepal’s Chhetri-Bahun language and literature. The Khas language, originally the language of the Chhetri communities of Nepal’s western hills, was refined into present-day Nepali by the Bahun communities of the mid-hills, who, as members of the priestly caste, had a culture that valued religious learning—if only for men. Nepal’s ‘first poet,’ Bhanubhakta Acharya, translated The Ramayan into Nepali. As Nepal entered the modern era, the emphasis on education switched from religious to secular. It is no coincidence that with their erudition, Nepal’s Bahun men were overrepresented in the leadership of the movement for democracy in 1950. (There were many prominent members of Nepal’s other communities, but their numbers were disproportionately small.)

It is also no coincidence that the language of the Bahun community went on to become Nepal’s sole official language in the 1960’s, as a Panchayat-era tool to ‘unify’ —or assimilate—the nation’s diverse communities. I was, myself, a product of the education system of this era, studying all school subjects (other than English) in Nepali under the New Education System. The privileging of the Nepali language segregated native speakers of Nepali from non-native speakers. Today, Bahun men remain overrepresented in all professional sectors that privilege those with a formal education: politics, governance and bureaucracy, the law, the education system itself, the media and of course literature. This is the direct outcome of the New Education Policy of the Panchayat era.

Power in Nepal lies in the Nepali language: being able to use it either to express the truth or to lie and dodge and obscure. (The convoluted, and even contradictory, language around citizenship rights in the 2015 Constitution are a prime example of this.) There is nothing inherently good or bad about any particular language, but all languages can be put to good and bad uses. When a state uses one particular language to silence others, or to disallow and demean and exclude vast portions of the population, it becomes a sharp tool of state power. Which is not to say that it can’t still be beautiful.

Much of the literature I read in the mid-1990s was also written in the Panchayat era. More than three quarters of the authors I was reading were Bahun men. The more deeply I read Nepali literature, the more I came to love the language and the stories it had produced. These stories were urgent and under-appreciated. For at the global scale, Nepali isn’t a powerful language. It is a language of the powerless. The absence of ‘outsiders,’ including women, in Nepali literature never stopped needling me—but it was years before I realized that this absence was in fact structured into the history of the language and of Nepal’s literary production.

The after effects of the Panchayat era linger on today, even after the language rights movements of the 1990s expanded the space for Nepal’s other languages. Nepal now recognizes 123 national languages, but no other language enjoys state resources—and state protectionism—as does the Nepali language.

There have been several attempts, particularly in literature, to address the structural exclusion of non-Nepali speakers that has resulted from this history. There is, of course, the publication of literature in languages other than Nepali, which Nepal Bhasa organizations are doing with particular alacrity. Nepal’s other major languages lag behind: Maithili, Bhojpuri, Tharu, Tamang, Magar, Bajika, Doteli and Awadhi publishers are few and far between.

There is also an important attempt, within Nepali-language literature, to wrest the language away from its ‘high,’ or formal, written form, and to write in the ‘low,’ or informal, spoken form. Writers from the earlier generation (such as Khagendra Sangraula) did this deliberately by writing in vernacular dialect in certain works (such as Junkiriko Sangeet, where the characters speak in a particular Dalit dialect from the mid-hills). The generation that was at its prime in the 1990s—including poets Bimal Nibha and Shrawan Mukarung and writers Narayan Dhakal, Aahuti and Sita Pandey—moved towards informal Nepali as if, subconsciously, in search of more natural, lively and realistic expressions. A younger generation of writers has embraced this informal style more wholeheartedly.

The work of fiction writers such as Buddhi Sagar, Kumar Nagarkoti, Anbika Giri and Upendra Subba, and the work of poets such as Sarita Tiwari, Manisha Gauchan and Kewal Binabi—to mention just a few—capture the spirit of the post-1990 era in seeking a style of writing that is not just informal, but more open and inclusive, which is to say, more democratic. Their style of Nepali writing makes space for outsiders, for non-native speakers, for multilingual Nepalis: the majority.

I believe that this is expanding the scope of the Nepali language, enriching it and giving it greater flexibility and resilience. Only by being the language of the people will the language truly flourish and grow and evolve. Democratizing the Nepali language will also help it survive the influx of more powerful languages such as English and the scattering of the Nepali diaspora throughout the world.

There will always be purists who claim that a more democratic language amounts to a loss of quality or a lowering of standards.They will lament the dilution of ‘pure’ Nepaliin favour of what they consider a poor, bastardized, impure language. Those critics can take heart that with its cultural emphasis on learning and education, the Bahun community is more than capable of preserving their ‘high,’ formal style of Nepali, which must be properly understood as only one specific dialect of it. Indeed, much Nepali-language literature is still written in this formal style. There will always be readers who prefer this style of writing. (And as a writer I understand that ‘high’ writing is not without its pleasures.)

But for the majority, I believe that the Nepali language will—rightly—continue to evolve into more democratic, accessible and inclusive forms. What is lost in ‘purity’ is more than regained in the inclusion of the majority. Interestingly, literature has played a pioneering role in democratizing the Nepali language. The news media still prefers the old, inaccessible ‘high’ style of writing. As the Kantipur Media Group celebrates its twenty-fifth anniversary, perhaps its editors, reporters, analysts and columnists can look towards contemporary Nepali literature for examples of more inclusive and democratic forms of expression.

Manjushree Thapa’s latest book is her English translation of Indra Bahadur Rai’s novel about post-Independence Darjeeling, There’s a Carnival Today.

22.52°C Kathmandu

22.52°C Kathmandu