Miscellaneous

Measure impact, not adulation

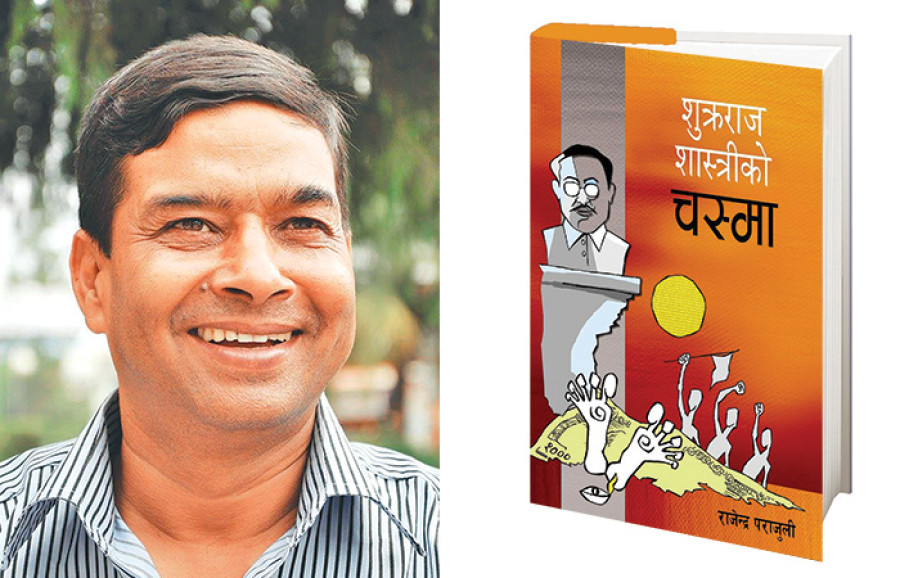

Rajendra Parajuli, whose collection of short stories—Shukraraj Shashtri ko Chasma—has been nominated for this year’s Madan Puraskar, has four story collections, one poetry anthology and a novel to his name. Parajuli,

Samikshya Bhattarai

Rajendra Parajuli, whose collection of short stories—Shukraraj Shashtri ko Chasma—has been nominated for this year’s Madan Puraskar, has four story collections, one poetry anthology and a novel to his name. Parajuli, a journalist by profession, writes about social realism in his books and believes that it is necessary for authors to critically analyse everything around them. In this conversation with the Post’s Samikshya Bhattarai, Parajuli talks about his writing, Nepali politics and more. Excerpts:

Your book Shukraraj Shashtri ko Chasma is a collection of 20 short, fictional stories that are imbued with social and political commentary. What is the inspiration behind your stories? What motivates you to write them?

The inspiration for my stories is our everyday society and the political condition of our country. After working as a journalist for years, I have come to the realisation that there are many shortcomings—both political and social—which are deeply rooted in our system. One of the major shortcomings, of course, is the attitude of political leaders that show a blatant lack of concern for marginalised communities. Although a few small efforts have been made to make Nepal a more inclusive society, much still needs to be done and we are still far behind in term of equality. These issues have been the inspiration to my stories. There are also two stories in the collection that were inspired by the toll the 2015 earthquakes took on common lives. The problem isn’t just at the governmental level, it is also deeply rooted in the public’s psyche. When we see a crisis or a problem, instead of being proactive, we just observe it from afar and at most complain passively. Through my stories, I try to critique the system, as well as become voice for those who cannot speak up for themselves.

A lot of your stories, including Shukraraj Shastri ko Chasma and Gulafi Suit, are very cynical of Nepali politics and get delivered to the readers without much of redemption for its characters. Do you think people have gotten to a point where they see no rescue from Nepali politics?

I have heard it ample times from my friends and readers that my writings are very pessimistic, especially when it comes to Nepali politics. I agree with them to an extent, and I do believe that there is no hope for Nepali politics, at least not in the near future. Our political system has gone through so many upheavals over the years and yet nobody has learnt any lesson. Nothing has changed for better. We’re still stuck in the same cyclical pattern and there doesn’t seem to be a way out. We lack both expertise and experts. I am not suggesting that redemption is impossible; all I’m saying is that it’s still a long way to go. I don’t want to write stories of hope when there is no silver lining in plain sight; so for now I’ll just be honest, even if it makes my writings pessimistic.

Having written three other short story collections, why do you prefer this medium to others. What do short stories allow you to do that, say, a novel doesn’t?

Short stories and novels are both very good mediums to tell stories, but I personally prefer the former because it gives me more room to play with words and tell what I want to without having to build on too much. Short stories, I believe, are an effective and an efficient way to convey the intended message. When it comes to writing a novel, both the author and the reader have to invest a lot of time and energy in the book. As I usually write to make people aware about a certain thing and bring to the spotlight issues of the voiceless and the marginalised, it is much easier to convey the message through short stories.

Nowadays, many writers are moving towards novels because the medium has a bigger market. But a big market doesn’t always translate into impact. If you want to make an impact you have to think and produce beyond entertainment—and my short stories are just the medium to do so. It is a good mixture of reality and creativity and produces a more profound effect on readers.

Besides, speaking from experience, I have written both short stories and novels and realised that I feel in my element while writing the former. I prefer complete solitude while writing and it’s not possible with novels as they take a lot of time.

Though fictional, some of your stories undoubtedly read a little autobiographical, for example, the story Parikampan. Tell us about the process you go through while creating your characters.

While a short story requires less time and effort, the process of creating a character is no less gruelling. There is a lot of work that I put into my characters, as they give life to my stories. My stories usually revolve around the marginalised, but I was raised in a Brahmin household here in Kathmandu, so to connect with my characters, I try my best to be one of them. I have travelled to remote places and lived like my characters before bringing them to life. I also interact with people resembling my characters and observe them. I think I invest way more time researching about the characters than I do writing about them. I think in books like mine, where social and political problems are vocalised, it is a must to have a very in-depth knowledge about the characters as they mirror the story and the society.

You’ve recently been shortlisted for a prestigious award. What would you say is the ultimate prize for a writer?

It is a really big honour to be shortlisted for awards but for writers, I think, the ultimate prize is and always should be the readers. The writers are nothing without their readers. The prize for a writer is the positive changes their books bring to society and the happiness that they are able to spread among readers through their work.

10.28°C Kathmandu

10.28°C Kathmandu